SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

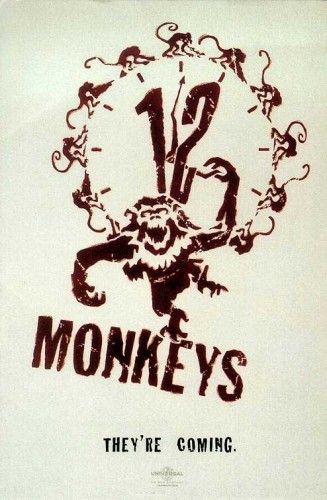

“An unknown and lethal virus has wiped out five billion people in 1996. Only one percent of the population has survived by the year 2035, and is forced to live underground. A convict named James Cole reluctantly volunteers to be sent back in time to 1996 to gather information about the origin of the epidemic (who he is told was spread by a mysterious Army Of The Twelve Monkeys) and locate the virus before it mutates so that scientists can study it. Unfortunately Cole is mistakenly sent to 1990, six years earlier than expected, and is arrested and locked up in a mental institution, where he meets Doctor Kathryn Railly, a psychiatrist, and Jeffrey Goines, the insane son of a famous scientist and virus expert.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Through the warped context of a fish-eye lens, we spy a dazed and confused prisoner named James Cole. His head shaved and tattooed with a bar-code, the hapless man sits suspended on an elevated chair in a chasm of a room. Prompted by a barrage of questions from scientists who finish each other’s enquiries as if they were part of some collective consciousness, he spouts nonsensical answers. Cole’s fragile psyche is already racked by the trauma of previous temporal shifts, and he’s bordering on psychosis. Suddenly the menacing scientists simultaneously burst into a rousing chorus of Blueberry Hill. This madcap hilarity fazes no one – why would it? Reality taking flight in the midst of crisis is an everyday occurrence in the films of Terry Gilliam, the auteur behind Jabberwocky (1977), Time Bandits (1981), Brazil (1985), The Adventures Of Baron Munchaussen (1988), The Fisher King (1991), Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas (1998), The Brothers Grimm (2005), Tideland (2005), and The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus (2009).

James Cole is played by a bald Bruce Willis in an early departure from his high-octane action heroics. One’s assessment of James Cole hinges on the interpretation of his unstable behaviour. Either one accepts that he’s actually traveling through time, or that his perception of time travel is little more than a manifestation of his disturbed mind. His love interest, Doctor Kathryn Reilly (Madeline Stowe), represents the rational side of contemporary humanity who must decide whether he’s a prophet or a madman. Due to the uncontrollable nature of his time-shifting, Cole encounters her in different years.

James Cole is played by a bald Bruce Willis in an early departure from his high-octane action heroics. One’s assessment of James Cole hinges on the interpretation of his unstable behaviour. Either one accepts that he’s actually traveling through time, or that his perception of time travel is little more than a manifestation of his disturbed mind. His love interest, Doctor Kathryn Reilly (Madeline Stowe), represents the rational side of contemporary humanity who must decide whether he’s a prophet or a madman. Due to the uncontrollable nature of his time-shifting, Cole encounters her in different years.

Technically, Twelve Monkeys (1995) is a remake, loosely based on La Jetee (1962), a classic example of French New Wave film-making by documentarian Chris Marker. Composed solely of black-and-white still photographs, this award-winning short film takes place in Paris after World War Three. An underground camp of scientists are desperately searching for a cure to save humanity’s dwindling population. They’ve surmised that the past holds the key to the present population’s survival. Since their format of time travel takes place primarily in the mind, one particular prisoner prone to vivid memories becomes the ideal candidate for these experiments. Through his travels he encounters a woman with whom he falls in love. After receiving assistance from mankind’s future, his final request is to be reunited with his lover. In a Twilight Zone-style Catch-22 situation, the protagonist’s climactic rendezvous with the woman occurs at the moment of his own death.

Technically, Twelve Monkeys (1995) is a remake, loosely based on La Jetee (1962), a classic example of French New Wave film-making by documentarian Chris Marker. Composed solely of black-and-white still photographs, this award-winning short film takes place in Paris after World War Three. An underground camp of scientists are desperately searching for a cure to save humanity’s dwindling population. They’ve surmised that the past holds the key to the present population’s survival. Since their format of time travel takes place primarily in the mind, one particular prisoner prone to vivid memories becomes the ideal candidate for these experiments. Through his travels he encounters a woman with whom he falls in love. After receiving assistance from mankind’s future, his final request is to be reunited with his lover. In a Twilight Zone-style Catch-22 situation, the protagonist’s climactic rendezvous with the woman occurs at the moment of his own death.

The scribes of Twelve Monkeys, David Peoples and Janet Peoples, were in no way disposed to do a strict remake of the short film. The film’s executive producer, Robert Kosberg, approached the husband-wife writing team a few years before through Chuck Roven. Roven, the producer of Twelve Monkeys, had served in the same capacity on David Peoples’ directorial debut, Blood Of Heroes (1993). David Peoples’ writing career began when he was hired as co-writer on the cult classic Blade Runner (1982). Following that film’s critical success, Peoples was hired to work on genre films like Ladyhawke (1985) and Leviathan (1989), and a number of Peoples’ original screenplays were sold during the eighties, many undergoing lengthy studio development periods before seeing production, including Unforgiven (1992) and Soldier (1998).

The story of Twelve Monkeys began after they considered which themes from La Jetee held the most resonance for them. Their story is based around a post-apocalyptic society, with a prisoner protagonist traveling the time-line in search of a cure for a lethal virus that has almost wiped out the human race – or so it seems. Though some of La Jetee’s concepts ended up in the final script, they were approached from a completely different perspective. The Peoples did not allow the original short film to become a creative albatross hanging around their necks either, but they obviously had some concerns with dealing with the intricacies of time travel, a rather over-worked science fiction sub-genre. Wishing to avoid the temporal plot patterns employed by The Terminator (1984) and its sequels, they downplayed the need for special effects while writing the script.

The story of Twelve Monkeys began after they considered which themes from La Jetee held the most resonance for them. Their story is based around a post-apocalyptic society, with a prisoner protagonist traveling the time-line in search of a cure for a lethal virus that has almost wiped out the human race – or so it seems. Though some of La Jetee’s concepts ended up in the final script, they were approached from a completely different perspective. The Peoples did not allow the original short film to become a creative albatross hanging around their necks either, but they obviously had some concerns with dealing with the intricacies of time travel, a rather over-worked science fiction sub-genre. Wishing to avoid the temporal plot patterns employed by The Terminator (1984) and its sequels, they downplayed the need for special effects while writing the script.

Terry Gilliam’s track record as a master of cinematic chaos made him a linchpin for Twelve Monkeys. Even before putting pen to paper, the Peoples thought that Gilliam could bring some pizzazz to their script about fractured time, reality, fantasy, sanity and madness (their other dream choice was Ridley Scott, as David Peoples had befriended Scott years before when he rewrote Hampton Fancher’s script for Blade Runner). Since directing The Fisher King (1991), Gilliam had been toiling on a number of projects which never came to fruition. Lack of funds and script problems foiled both his anticipated adaptation of the Watchmen comic series, and an original script written with Richard La Gravanese called The Defective Detective. After missing out on the opportunity to retell A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court, Gilliam was ready to direct A Tale Of Two Cities, but his reinterpretation of the Charles Dickens novel came to a halt when lead actor Mel Gibson jumped ship to make Braveheart (1995). Free from any obligations and in need of work, Gilliam gladly turned to Twelve Monkeys to break his five-year dry spell.

Terry Gilliam’s track record as a master of cinematic chaos made him a linchpin for Twelve Monkeys. Even before putting pen to paper, the Peoples thought that Gilliam could bring some pizzazz to their script about fractured time, reality, fantasy, sanity and madness (their other dream choice was Ridley Scott, as David Peoples had befriended Scott years before when he rewrote Hampton Fancher’s script for Blade Runner). Since directing The Fisher King (1991), Gilliam had been toiling on a number of projects which never came to fruition. Lack of funds and script problems foiled both his anticipated adaptation of the Watchmen comic series, and an original script written with Richard La Gravanese called The Defective Detective. After missing out on the opportunity to retell A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court, Gilliam was ready to direct A Tale Of Two Cities, but his reinterpretation of the Charles Dickens novel came to a halt when lead actor Mel Gibson jumped ship to make Braveheart (1995). Free from any obligations and in need of work, Gilliam gladly turned to Twelve Monkeys to break his five-year dry spell.

Universal Pictures’ US$30 million budget for such an adventurous script is a far cry from some of Gilliam’s previous dealings with Hollywood studios. The last film he made for Universal, Brazil (1985), was infamous even before its release. Displeased with the film’s dark tone, Universal’s then-president Sid Sheinberg wanted to revoke Gilliam’s final cut privilege by changing the ending to be more upbeat. The director responded with a full-page ad in Variety accusing Sheinberg of unjustly holding up the film’s release. The deadlock ended with Gilliam’s cut remaining intact after the Los Angeles Critics Awards bestowed Brazil with honours for Best Picture, Best Screenplay and Best Director. This came about because the shrewd Gilliam had arranged a secret screening for critics.

Universal Pictures’ US$30 million budget for such an adventurous script is a far cry from some of Gilliam’s previous dealings with Hollywood studios. The last film he made for Universal, Brazil (1985), was infamous even before its release. Displeased with the film’s dark tone, Universal’s then-president Sid Sheinberg wanted to revoke Gilliam’s final cut privilege by changing the ending to be more upbeat. The director responded with a full-page ad in Variety accusing Sheinberg of unjustly holding up the film’s release. The deadlock ended with Gilliam’s cut remaining intact after the Los Angeles Critics Awards bestowed Brazil with honours for Best Picture, Best Screenplay and Best Director. This came about because the shrewd Gilliam had arranged a secret screening for critics.

Gilliam followed that with The Adventures Of Baron Munchaussen, a tale about an Eighteenth Century German monarch given to wild fantasies. Its production was halted by the film’s financiers when the budget soared to a rumoured US$45 million. For a time it seemed doubtful that Gilliam would ever again work within the confines of the major studio system. He redeemed himself in the eyes of executives, however, by coming in on-schedule and under-budget with what is considered by many his most accessible (and therefore most commercially successful) film, The Fisher King. Twelve Monkeys marks the second time Gilliam has directed a film from someone else’s script. Though a number of projects he slated to direct were adaptations, Gilliam prefers to work with his own material. The exaggeration of his style is singular and any project he directs carries his creative imprint.

Gilliam followed that with The Adventures Of Baron Munchaussen, a tale about an Eighteenth Century German monarch given to wild fantasies. Its production was halted by the film’s financiers when the budget soared to a rumoured US$45 million. For a time it seemed doubtful that Gilliam would ever again work within the confines of the major studio system. He redeemed himself in the eyes of executives, however, by coming in on-schedule and under-budget with what is considered by many his most accessible (and therefore most commercially successful) film, The Fisher King. Twelve Monkeys marks the second time Gilliam has directed a film from someone else’s script. Though a number of projects he slated to direct were adaptations, Gilliam prefers to work with his own material. The exaggeration of his style is singular and any project he directs carries his creative imprint.

Setting the past, present and future of Twelve Monkeys in Philadelphia and Baltimore were arbitrary choices by the screenwriters, in line with a plot point in which a character travels between two cities six hours apart from one another. This calculation, however, proved to be slightly off. Oddly enough, though, when scouting locations, Gilliam found that these cities conveyed what he believed to be one of the story’s primary sentiments – that of materialism gone awry. To represent Cole’s past (our present) in the film, Gilliam manipulated architectural situations as he did with the Gothic surroundings of New York City in The Fisher King. It’s quite obvious that, like Brazil, the imposing grandeur of German architecture and expressionist cinema influence the future sequences of Twelve Monkeys as well.

Setting the past, present and future of Twelve Monkeys in Philadelphia and Baltimore were arbitrary choices by the screenwriters, in line with a plot point in which a character travels between two cities six hours apart from one another. This calculation, however, proved to be slightly off. Oddly enough, though, when scouting locations, Gilliam found that these cities conveyed what he believed to be one of the story’s primary sentiments – that of materialism gone awry. To represent Cole’s past (our present) in the film, Gilliam manipulated architectural situations as he did with the Gothic surroundings of New York City in The Fisher King. It’s quite obvious that, like Brazil, the imposing grandeur of German architecture and expressionist cinema influence the future sequences of Twelve Monkeys as well.

The future’s sense of encroaching decay is best conveyed by humanity being forced to engineer a retro-fitted society for themselves, leading them to fashion tools and instruments out of the ruins of civilisation. Such was the case with Cole’s protective suit against 2035’s lethal atmosphere. Nicknamed ‘The Human Condom’ it’s a spacesuit-like 130-pound plastic sheath covered with a slew of motors, gears and valves that look like they’ve been salvaged from the planet’s surface. Underlining it is a bodysuit of pure latex. The irony of Twelve Monkeys lies in the fact that, despite all of humanity’s technological advancements, it’s a natural organism which devastates the race. In contrast to this disregard for the power of mother nature, Gilliam went for a more organic version of time travel. Housed in a former power plant, the time machine was actually a number of eighteen-foot tube-like steel turbines internally lit with blue neon. Cole is transported into it naked, his only protection is a thin cocoon of plastic.

The future’s sense of encroaching decay is best conveyed by humanity being forced to engineer a retro-fitted society for themselves, leading them to fashion tools and instruments out of the ruins of civilisation. Such was the case with Cole’s protective suit against 2035’s lethal atmosphere. Nicknamed ‘The Human Condom’ it’s a spacesuit-like 130-pound plastic sheath covered with a slew of motors, gears and valves that look like they’ve been salvaged from the planet’s surface. Underlining it is a bodysuit of pure latex. The irony of Twelve Monkeys lies in the fact that, despite all of humanity’s technological advancements, it’s a natural organism which devastates the race. In contrast to this disregard for the power of mother nature, Gilliam went for a more organic version of time travel. Housed in a former power plant, the time machine was actually a number of eighteen-foot tube-like steel turbines internally lit with blue neon. Cole is transported into it naked, his only protection is a thin cocoon of plastic.

During the film’s interrogation scenes, Gilliam indulges in a favourite pastime – bashing the exalted role that television plays in modern culture. In one of many visual extrapolations from the Peoples’ script, Gilliam designed a huge video ball for the scientists to use as a grand inquisitor. In the script, the fifteen monitors were to display catastrophes from mankind’s past, such as famines, wars and disasters. In the finished print, however, these images proved difficult to see, so Gilliam replaced them with the distorted faces of the scientists, which is far more alienating. With all these critiques on the dangers of humanity letting technology run so rampant that it overtakes us, some may argue that Twelve Monkeys shares more than an aesthetic resemblance to the dystopia of Brazil.

During the film’s interrogation scenes, Gilliam indulges in a favourite pastime – bashing the exalted role that television plays in modern culture. In one of many visual extrapolations from the Peoples’ script, Gilliam designed a huge video ball for the scientists to use as a grand inquisitor. In the script, the fifteen monitors were to display catastrophes from mankind’s past, such as famines, wars and disasters. In the finished print, however, these images proved difficult to see, so Gilliam replaced them with the distorted faces of the scientists, which is far more alienating. With all these critiques on the dangers of humanity letting technology run so rampant that it overtakes us, some may argue that Twelve Monkeys shares more than an aesthetic resemblance to the dystopia of Brazil.

Gilliam’s obvious lack of optimism with his adult contemporaries is a motif that runs throughout his body of work. He is forced to strike a compromise between his mind’s childlike view of life, and the experienced knowledge of the seventy-year-old body that it now inhabits. His coy sense of naivete feeds such diverse yet thematically similar films. And it’s on that thought I’ll bid you a good night and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to put goose-bumps on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick and chumpy you could carve it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews