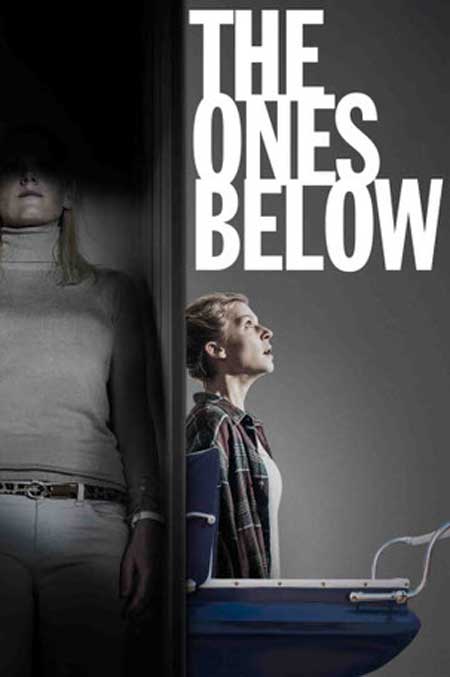

SYNOPSIS:

After giving birth to her first child, a woman (Clémence Poésy) starts to believe that her downstairs neighbors have sinister intentions.

REVIEW:

The Ones Below is a slow burn.

No, strike that. The Ones Below is a leisurely, gradual, protracted, dawdling, painstakingly slow burn. In fact, it burns about as slowly as anything could possibly burn. It doesn’t spark, it doesn’t blaze, and it never bursts into flame. But The Ones Below smolders portentously from its opening frames until its final, lingering, heart-breaking shot, and it taps into a fertile thematic well of moral impotency, guilt, and postpartum despair.

British couple Kate and Justin are expecting their first baby, and their new neighbors in the flat downstairs—Theresa and Jon—are expecting their first, as well. Just as the two couples are starting to get to know each other, the peculiar Theresa and Jon lose their unborn son in a tragic accident for which several of the four share some measure of responsibility. In the wake of the accident, their relationship grows cold and fractured, poisoned by blame and guilt and the shadow of the awful tragedy. Later, after Kate gives birth, the four tentatively put their enmity behind them and resume their friendship, but it is unclear if Theresa and Jon are moved to reconcile out of genuine warmth and affection or if there is something more malignant behind their rapprochement.

Kate (French actress Clemence Poesy) is a reserved woman whose strained and complicated relationship with her mother has made her reluctant to start a family of her own. She is drawn to her effusive, passionate neighbor, and initially sees in Theresa (Laura Birn) the opportunity for the warm and intimate friendship that her life is missing. When the accident fractures their relationship, Kate wants desperately to put the pieces back together, and she sees her newborn child as a means of salving the wounds that were torn open by Theresa’s miscarriage. Soon, though, Kate begins to suspect that the constant graciousness and solicitude of Theresa and Jon (David Morrissey) may be just a façade, but her guilt—combined with the exhaustion and isolation of early motherhood—lead both her and Justin (Stephen Campbell Moore) to question and doubt her perceptions.

Though The Ones Below shuns nearly every trope of traditional horror, it does effectively conjure suspense and anticipation, constructing a narrative around one central question: are Theresa and Jon the plotting, insidious monsters that Kate begins to suspect they are, or are Kate’s suspicions just a manifestation of her own upbringing and shame over her pre-maternal ambivalence. Shortly after losing her child, in a vicious explosion of grief and despair, Theresa spits venomously at Kate: “You don’t deserve that thing inside you!” That moment of rage triggers Kate, both foreshadowing and putting into motion the events that lead to the film’s final, terrible transgression.

The Ones Below taps a rich and well-trafficked thematic well, though it does so in original and thought-provoking ways. Whether one reads it as a literal or metaphorical examination of postpartum depression, its central premise clever manifests and plays upon the tsunami of emotions and experiences that accompany new parenthood in general and new motherhood in particular: joy, fatigue, guilt, hope, loneliness, anxiety, pride, vulnerability, fear, awe, and upheaval. Both Kate and Justin are subject to all these influences. But it is the social and filial expectations of motherhood that serve to exacerbate Kate’s stress and isolation, and those forces conspire to feed her paranoia and fear: paranoia over what Theresa and Jon may be up to, and fear that Theresa’s bitter rebuke may have been right. If she is unsure that she ever even wanted her child, how could she possibly deserve him?

In the flat below, however, there is no such trepidation or doubt: Theresa and Jon crave nothing more than they do a baby. Jon has carefully plotted and constructed his life and his relationship with Theresa specifically to fulfill that one singular ambition. And she, achingly, understands that her value to Jon is wholly and exclusively in her ability to give him and then raise his child. Her wild love and passion for Jon, then, motivate everything she does.

The combustion of these smoldering and discordant sentiments and motivations ultimately plays out in an almost perfunctory, matter-of-fact climax. There is conflict, and there is resolution, all unfolding inexorably through a dreamy, languid denouement. In the film’s final moments, one character assures quietly, “It’s much better this way,” a declaration of complete and utter moral defiance and self-absolution.

The film itself may be agnostic on those sentiments, but it is that unwavering expression of moral righteousness and certitude in the wake of a monstrous deed that ultimately encapsulates the true horror at the rotten core of The Ones Below.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Mostly the film is dull and the ending is unsatisfying and wholly unbelievable. The movie gets progressively dumber the deeper you get into the running time. The characters (especially at the end) have to behave in an oblivious fashion for the director to get the ending he desires.

Not awful but weak and critically overrated.