SYNOPSIS:

“Robert Scott Carey and his beloved wife Louise Carey are spending vacation on the motor boat of his brother Charlie. When Louise goes to the galley to bring a beer to Robert, he is engulfed by a weird mist. Six months later, Robert is sprayed by insecticide and when he goes to the doctor for the routine medical examination, he realizes that he had become shorter. Then he goes to a laboratory to be examined by scientists and they conclude that the combination of the mist with the insecticide has caused the effect. When Robert is only 93 centimetres tall, the scientists find a formula and he stops shrinking and meets the midget Clarice that gives hope to him. But soon he continues to shrink and he moves to a dollhouse. One day, Louise is not in the house and their cat breaks in Robert’s house. However he succeeds to escape to the basement and Louise believes that the cat has eaten him. Robert is trapped in the cellar and he has to struggle to survive against a spider and to find nourishment.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

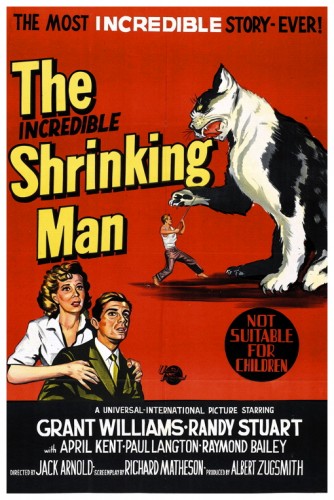

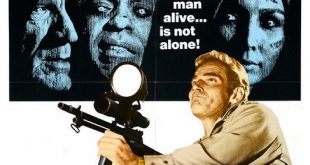

During and after the Vietnam war, the image of our bodies as intensely vulnerable to decay and mutilation reached its climax (or nadir) in the work of George Romero, David Cronenberg and others. Such images however did not spring up by parthenogenesis – they were the wild children of an already existing family of images, a family with a history. A film that evoked the paranoia of man-injured-by-technology with great precision and flair was the excellent The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), the best of Jack Arnold‘s films for Universal Studios and probably the most interesting science fiction film of that year.

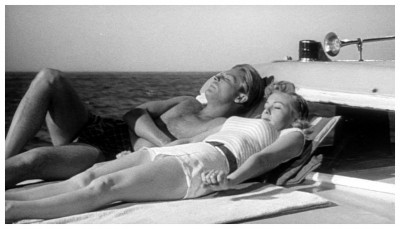

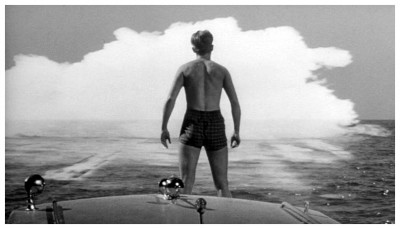

After passing through a radioactive cloud while on a motor boat, combined with later exposure to dangerous pesticides, Scott Carey (Grant Williams) begins to decrease in size, slowly at first, and then much faster. By the time he’s a mere three feet tall it’s become obvious to both his wife Louise (Randy Stuart) and himself that things are never going to be the same. Believing that the shrinking has stopped, he strikes up a relationship with an attractive midget girl (April Kent) he meets in a park, but the affair comes to an end when he realises that he is growing still smaller.

After passing through a radioactive cloud while on a motor boat, combined with later exposure to dangerous pesticides, Scott Carey (Grant Williams) begins to decrease in size, slowly at first, and then much faster. By the time he’s a mere three feet tall it’s become obvious to both his wife Louise (Randy Stuart) and himself that things are never going to be the same. Believing that the shrinking has stopped, he strikes up a relationship with an attractive midget girl (April Kent) he meets in a park, but the affair comes to an end when he realises that he is growing still smaller.

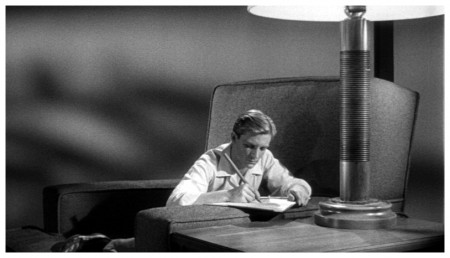

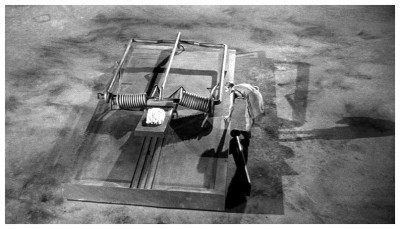

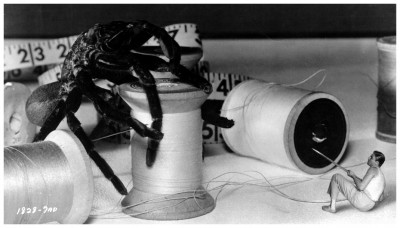

Reduced to living in a doll house he makes a brave attempt at coming to terms with things but suffers a further disaster when his pet cat, which gets into the room while his wife is out shopping, attacks the doll house and attempts to eat him. Fleeing the cat he falls down the steps into the cellar and enters a whole new world of nightmares where a leaking boiler seems like Niagara Falls and an ordinary spider is the size of a Volkswagen. He finally overcomes all the threats to his survival but still continues to shrink, and we last see him preparing to leave the cellar (he is now small enough to pass through a fly-screened window) and into the garden. “To God there is no zero. I still exist!” we hear him say as he seems to disappear completely.

Reduced to living in a doll house he makes a brave attempt at coming to terms with things but suffers a further disaster when his pet cat, which gets into the room while his wife is out shopping, attacks the doll house and attempts to eat him. Fleeing the cat he falls down the steps into the cellar and enters a whole new world of nightmares where a leaking boiler seems like Niagara Falls and an ordinary spider is the size of a Volkswagen. He finally overcomes all the threats to his survival but still continues to shrink, and we last see him preparing to leave the cellar (he is now small enough to pass through a fly-screened window) and into the garden. “To God there is no zero. I still exist!” we hear him say as he seems to disappear completely.

Scientifically it’s nonsense of course. It ignores the problems of mass, for instance (as my old friend Ray Bradbury used to say, “If you have a brain the size of a mouse, you’re going to want to run around walls and eat cheese.”) but it’s still good science fiction because its central protagonist undergoes a science-related experience which fundamentally alters his perception of the universe. It’s also a multi-layered film, its underlying theme being not so much concerned with the physical problems of a man who shrinks, but with the basic psychological fears that his bizarre situation stands as metaphor, such as the fear of ceasing to exist as a separate entity, of dying, and of sexual inadequacy. The shrinking man first becomes as a child compared to his adult-sized wife, then reaches the point where he is kept by her in a doll house, possibly the ultimate sexual humiliation.

Scientifically it’s nonsense of course. It ignores the problems of mass, for instance (as my old friend Ray Bradbury used to say, “If you have a brain the size of a mouse, you’re going to want to run around walls and eat cheese.”) but it’s still good science fiction because its central protagonist undergoes a science-related experience which fundamentally alters his perception of the universe. It’s also a multi-layered film, its underlying theme being not so much concerned with the physical problems of a man who shrinks, but with the basic psychological fears that his bizarre situation stands as metaphor, such as the fear of ceasing to exist as a separate entity, of dying, and of sexual inadequacy. The shrinking man first becomes as a child compared to his adult-sized wife, then reaches the point where he is kept by her in a doll house, possibly the ultimate sexual humiliation.

The author of the book and the screenplay itself was the prolific Richard Matheson, a writer who based his career on exploring aspects of paranoia. His novel I Am Legend, which has been filmed at least three times, is possibly the ultimate paranoia story, though his script for Steven Spielberg‘s Duel (1971) comes a close second. Matheson was responsible for a record number of unforgettable genre hits which include The House Of Usher (1960), Pit And The Pendulum (1961), Burn Witch Burn (1962), Tales Of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), Comedy Of Terrors (1963), The Devil Rides Out (1968), The Legend Of Hell House (1973), What Dreams May Come (1998), Real Steel (2011) as well as made-for-television movies like The Night Stalker (1972), The Night Strangler (1973) and Trilogy Of Terror (1975). Matheson also scripted sixteen immortal episodes for Rod Serling‘s original Twilight Zone series. Furthermore, a large percentage of The Simpsons Treehouse Of Horror stories are inspired by Matheson’s work!

The author of the book and the screenplay itself was the prolific Richard Matheson, a writer who based his career on exploring aspects of paranoia. His novel I Am Legend, which has been filmed at least three times, is possibly the ultimate paranoia story, though his script for Steven Spielberg‘s Duel (1971) comes a close second. Matheson was responsible for a record number of unforgettable genre hits which include The House Of Usher (1960), Pit And The Pendulum (1961), Burn Witch Burn (1962), Tales Of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), Comedy Of Terrors (1963), The Devil Rides Out (1968), The Legend Of Hell House (1973), What Dreams May Come (1998), Real Steel (2011) as well as made-for-television movies like The Night Stalker (1972), The Night Strangler (1973) and Trilogy Of Terror (1975). Matheson also scripted sixteen immortal episodes for Rod Serling‘s original Twilight Zone series. Furthermore, a large percentage of The Simpsons Treehouse Of Horror stories are inspired by Matheson’s work!

Sadly passing away early this year, his work is carried on by several talented offspring, including award-winning horror author Richard Christian Matheson, and Christian Richard Matheson is a screenwriter of such fantastic films as Bill And Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) as well as their Bogus Journey To Hell (1991). While Matheson’s ending of The Incredible Shrinking Man is hopeful, the entire film (though enjoyable) is quite upsetting as we watch Scott Carey shrink in body-size and self-respect. His home is no longer a sanctuary but a booby-trapped battlefield where every household item is potentially a weapon that could destroy him. His wife remains loyal but, being of normal size, becomes the prime reason for his sense of inferiority and, through his eyes, we take a new look at things and people we’ve taken for granted. There is an underlying theme dealing with male sexual impotence. The film’s most touching scene has Scott Carey – now three feet tall and uncomfortable talking with his wife – striking up a relationship with Clarice, the attractive midget sideshow performer.

The film becomes an exercise in paranoia in that it concerns a man who realises that all his familiar and comfortable surroundings, including his wife and neighbours, are becoming increasingly threatening, that his world is not the safe place it seemed but one of pure nightmare. He becomes, “The incredible shrinking freak! One more joke for the world to laugh at!” Indeed, the audience laughter that greets the first scenes of him (perched on seat cushions or struggling to lift the telephone receiver with both hands) is most likely to be of the nervous variety. It’s at this point that Matheson and director Arnold turn the screw, and Scott Carey’s nightmare moves from the conceptual to the physical, commencing with the superb image of him opening his doll’s house front door to the massive squealing face of the family cat, and continuing to a series of perils culminating in a nail-biting life-or-death struggle with a marauding spider.

The film’s biggest surprise is its cosmic finale in which Scott Carey, suddenly free of fear and hunger, shrinks from microscopic to atomic, dissipating into the atmosphere, still conscious but with no physical dimensions, his narration concluding, “And in that moment I knew the answer to the riddle of the infinite – that existence begins and ends in man’s conception, not nature’s.” On a technical level the film is also above-average with intelligent direction by Jack Arnold, fairly convincing special effects by Clifford Stine (the mattes, forced perspective and split-screens are very good), and the cast deliver capable performances, especially Grant Williams as the shrinking Scott Carey and Randy Stuart as his well-meaning wife.

The film’s biggest surprise is its cosmic finale in which Scott Carey, suddenly free of fear and hunger, shrinks from microscopic to atomic, dissipating into the atmosphere, still conscious but with no physical dimensions, his narration concluding, “And in that moment I knew the answer to the riddle of the infinite – that existence begins and ends in man’s conception, not nature’s.” On a technical level the film is also above-average with intelligent direction by Jack Arnold, fairly convincing special effects by Clifford Stine (the mattes, forced perspective and split-screens are very good), and the cast deliver capable performances, especially Grant Williams as the shrinking Scott Carey and Randy Stuart as his well-meaning wife.

The success of The Incredible Shrinking Man produced the inevitable cheap imitations, one of the first being The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) produced and directed the same year by Bert I. Gordon aka Mister BIG, a filmmaker so determinedly crass in his work that he makes Roger Corman look like the genius many people say he is, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

The success of The Incredible Shrinking Man produced the inevitable cheap imitations, one of the first being The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) produced and directed the same year by Bert I. Gordon aka Mister BIG, a filmmaker so determinedly crass in his work that he makes Roger Corman look like the genius many people say he is, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

The book is an unforgettable read. It’s truly scary and a work of art.

The novel raises questions of what it means to be a man in 1950s white middle class suburban America, and the fears associated with not acting like a man, as imagined through the fantastical idea of slowly shrinking in height. As Scott Carey shrinks, he experiences estrangement with his own body, and in his relationships with people around him. As he shrinks in size he loses confidence in his masculinity and becomes intimidated by his wife, child, and even pet cat. His place as head of the house ebbs away until he is banished to the basement, unable to go to work. Normal objects appear alien and threatening, such as the oil burner that causes him pain from the sound, or the spider which chases him. His fears are presented as the result of his failure to recognize and dispense with his concepts of “normality”, particularly those concepts of normality which are associated with the role of the “normal” middle-class masculinity in the 1950s.