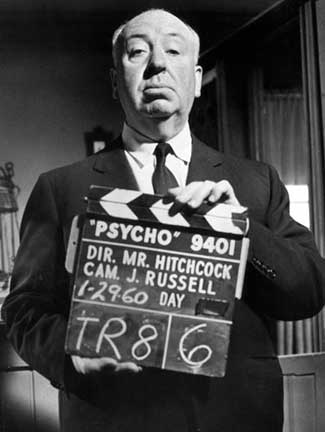

Tippi Hedren. Janet Leigh. Grace Kelly. Eva Marie Saint. Kim Novak. Alfred Hitchcock’s consistent casting of platinum blondes has painted a target on his infamously rotund figure for being a misogynistic director hampered by an obvious fetish. His casting of the beautiful blonde – who he found to be at their most alluring when they were least clothed – led to a motif in the horror industry that is still alive and kicking today. However, as one of my personal favorite writers once said, “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it’s time to pause and reflect.”

Tippi Hedren. Janet Leigh. Grace Kelly. Eva Marie Saint. Kim Novak. Alfred Hitchcock’s consistent casting of platinum blondes has painted a target on his infamously rotund figure for being a misogynistic director hampered by an obvious fetish. His casting of the beautiful blonde – who he found to be at their most alluring when they were least clothed – led to a motif in the horror industry that is still alive and kicking today. However, as one of my personal favorite writers once said, “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it’s time to pause and reflect.”

That same author also said, “Write drunk, edit sober.” But perhaps we’ll revisit that for another time…

Regardless, there’s truth in the former quotation and perhaps when it comes to Hitchcock, Hollywood has often found itself having to pause and reflect on his work. The perfect example in relation to the grandfather of the slasher genre would be the fact that he was snubbed from ever winning an Academy Award as a director. To make good on this massive oversight, the Academy decided to give the five-time-bridesmaid-but-never-the-bride director the “We’re sorry we f*cked you over, but now that you’re old, we hope that you accept” Irving G. Thalberg Award in 1968.

Mind you, the Irving G. Thalberg Award isn’t even the Lifetime Achievement Award – an award that Mary Pickford was awarded in 1975 for having really great curls and Chuck Jones was awarded in 1995 for being the first animator to depict a rabbit in drag (and Roger Corman is set to receive his own Lifetime Achievement Award this year). Instead, the Thalberg Award differs in that instead of receiving the Oscar statuette, the recipient receives a miniature statuette of Thalberg’s head – an old-time producer who won three Oscars himself.

Obviously, I’m being facetious when I jab at Pickford and Jones, but let’s face it, a man who is largely considered one of the greatest, if not the greatest, director of all-time and has six films listed on the Top 100 Films of All-Time by AFI, should’ve gotten a bit more than a bronzed voodoo head of a dead producer.

But I digress…

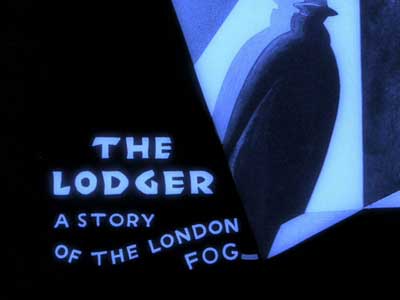

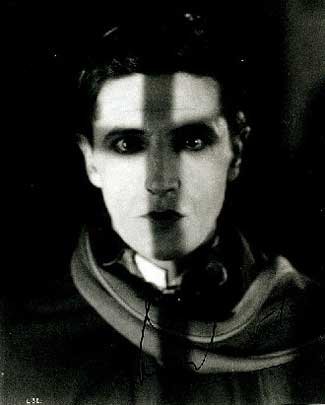

Long before Hitchcock assisted in launching the careers of the aforementioned starlets, the British-born director, he began his trope of blonde victims with a young actress named June Tripp in one of his earliest films, the 1926 silent B&W, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog. Perhaps it doesn’t come as a surprise to horror fans that this early film of Hitchcock’s is about a Jack the Ripper-like serial killer who stalks actresses with blonde curls. And June Tripp, playing the female lead Daisy Bunting, just so happens to have blonde curls. Daisy also happens to be the object of affection for two men: detective Joe Chandler (played by Malcolm Keen) and Jonathan Drew better known as simply The Lodger (played by 1920s British heartthrob Ivor Novello). If the lack of empowerment Daisy posesses (at least at the surface) isn’t drawn out enough, Hitchcock also makes certain to include Daisy stripping down to the bare minimum before hopping into a tub while The Lodger – who Hitchcock leads the audience to believe is the Jack the Ripper-like killer whom the public knows as “The Avenger” – attempts to open the bathroom door.

Long before Hitchcock assisted in launching the careers of the aforementioned starlets, the British-born director, he began his trope of blonde victims with a young actress named June Tripp in one of his earliest films, the 1926 silent B&W, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog. Perhaps it doesn’t come as a surprise to horror fans that this early film of Hitchcock’s is about a Jack the Ripper-like serial killer who stalks actresses with blonde curls. And June Tripp, playing the female lead Daisy Bunting, just so happens to have blonde curls. Daisy also happens to be the object of affection for two men: detective Joe Chandler (played by Malcolm Keen) and Jonathan Drew better known as simply The Lodger (played by 1920s British heartthrob Ivor Novello). If the lack of empowerment Daisy posesses (at least at the surface) isn’t drawn out enough, Hitchcock also makes certain to include Daisy stripping down to the bare minimum before hopping into a tub while The Lodger – who Hitchcock leads the audience to believe is the Jack the Ripper-like killer whom the public knows as “The Avenger” – attempts to open the bathroom door.

The relentless closeups of body shots whether it be bare feet or eyes or mouths are techniques recognizable to even the most casual of horror fans – and in cultural studies, academics call these sorts of things “residual” in that the sticky residue of past techniques or messages or tropes or motifs of earlier media find their way into contemporary media…sometimes it’s done purposefully and skillfully – that is, the director is aware of it, which we can call an allusion – and sometimes it’s done without any real knowledge behind the craft – I.E. a horror filmmaker who turns to his cameraman and includes on the shot list “CU of boobs” because “you’ve gotta have a closeup of boobs in a horror film, man.”

Either way, the parallels to Psycho in The Lodger are obviously uncanny, but the motifs are set down by Hitchcock in the latter and cinematic history is made. Nowadays, a pretty blonde stripping down to her skin before hopping into the shower while some skeezy, shady dude sits outside her door as the camera gazes over her body in a demonstratively violating manner is pretty much stock for even the most half-hearted attempts at a horror film. Some accomplish it better than others – one of the more interesting examples of this would be from The House on the Edge of the Park where Deodato plays with David Hess’s POV while Annie Belle showers.

It’s a recurring motif in horror that has become a dartboard for mainstream critics and religious nuts who are afraid of nudity because it might somehow offend Jesus. As always, I must take issue with mainstream thought and, instead suggest that – in spite of the shallow characterization and obvious objectification of Daisy…let’s keep in mind it’s a silent 1926 film…characterization in screenwriting isn’t necessarily as sophisticated in its conventions as it is capable of in 2010 – the character of Daisy is far more complex than simply superficial, but has a side to her that arguably offers an astute portrayal of a woman’s struggle with the oppressive nature of social roles pressed upon her.

However, let’s begin with the idea that the film fails as a progressive film. An obvious hole in the view that that the film is progressive in its portrayal of a female in society is that Hitch automatically falls into the trap of placing woman as victim. Daisy is, arguably, being hunted. She’s being hunted by Joe who wants to marry her. And she’s being hunted by The Lodger who wants to get his shag-wow on with her.

Moreover, because she has blonde curls, she’s arguably being hunted by The Avenger (who Hitchcock never reveals the identity of…interviews with Hitch – notably his infamous recordings with Trauffaut – suggest that he intended for The Avenger to be The Lodger, however, studio heads wouldn’t allow it as Ivor Novello was a heartthrob and therefore, couldn’t be killed nor be portrayed as a killer as this was considered bad business at the time). Furthermore, it could also be argued that Hitchcock is portraying Daisy as victim of social structures.

She is an oppressed female. She’s largely kept at home by her parents and when she does go out, it’s usually to work as a model walking a runway and showing off clothing that she, herself, could never own – but takes an enormous interest in when The Lodger attempts to woo her by buying her a dress she modeled at a show he attended. Moreover, she’s also expected to marry Joe – a man whose entire life is about regulation and rules. He is, after all a detective, and in a most wonderfully symbolic and sexually playful moment, Joe handcuffs Daisy as a joke and she flips the f*ck out as he playfully laughs before releasing her, disappointed at her horror of being tied up by her creepy boyfriend.

That said, Daisy is clearly fighting all of these structures, rules, and expectations that have forced upon her. She is almost immediately attracted to The Lodger because social and legal structures don’t apply to him. Rather than be stuck to one home as Daisy is, The Lodger moves from place to place untethered to any singular household. His physical mobility is as free as Daisy’s is restricted. Moreover, The Lodger is unrestricted by money. Joe promises he will put a ring on Daisy’s finger as soon as he gets handcuffs on The Avenger’s wrists – what one has to do with the other seems incoherent, though it could be interpreted that by catching The Avenger means a promotion of sorts for Joe. The Lodger, on the other hand, leaves money just sitting around in his room in such a nonchalant manner that even Daisy’s mother seems tempted to help herself to one of his Uncle Scrooge-like stacks of coins.

It’s hardly any surprise that Daisy rejects Joe in favor of The Lodger in this skillfully setup love triangle. Joe, a man of the law and practically an extension of her immediate family, treats Daisy like a child. His idea of flirtation is to cut hearts out of cookie dough and toss them to her like they’re in kindergarten making sugar cookies for a school Christmas project. The Lodger, on the other hand, sits down with her to play the adult game of Chess – a game of foresight, thought, and conquering of pieces (and it’s by no small coincidence that in another conveniently placed CloseUp, The Lodger picks up the very phallic fireplace poker mid-game to stoke up the flames to figuratively and literally heat up the room).

While I don’t want to ruin the entire film for readers who haven’t been exposed to this gem of cinematic history, I would point out that it’s worth keeping an eye on just how much Hitchcock plays with triangles and the number three. The murders take place on Tuesday – the third day of the week. The Lodger stays in an apartment on the third floor. The Lodger keeps three stacks of coins on a mantle. The ceiling fixture that continues to receive its own closeup holds three lights. Three triangles are in almost every title card. Each shot composition often has three actors in the shot, placed in a triangle in relation to the camera (or audience).

One of Hitchcock’s favorite angles while in The Lodger’s room involves placing in the middle of the screen a series of three shelves on the wall and on each shelf are three items. Towards the end, there’s also an obvious allusion to Jesus on the cross – often related to the Holy Trinity. It seemingly never-ending web of intricacy that a 25-year-old Hitchcock weaved for audiences, and as crude as it may be in comparison to his later work, I highly recommend it for any one with the patience and wherewithal to sit through a B&W silent film – and I invite audiences to pay close attention to Daisy and decide for themselves whether Hitch is being a misogynist pig or progressive critic.

One of Hitchcock’s favorite angles while in The Lodger’s room involves placing in the middle of the screen a series of three shelves on the wall and on each shelf are three items. Towards the end, there’s also an obvious allusion to Jesus on the cross – often related to the Holy Trinity. It seemingly never-ending web of intricacy that a 25-year-old Hitchcock weaved for audiences, and as crude as it may be in comparison to his later work, I highly recommend it for any one with the patience and wherewithal to sit through a B&W silent film – and I invite audiences to pay close attention to Daisy and decide for themselves whether Hitch is being a misogynist pig or progressive critic.

Whatever the case may be, The Lodger is a landmark in horror. The early classic contains many of the same motifs we see today: objectification of body parts, POV angles, female as victim, the classic shower/bathroom scene, etc. (and keep an eye out for the first scene introducing The Lodger as one can’t help but believe that William Friedkin had to have seen the film before working on The Exorcist). The film also lays the groundwork for much of the controversy involving Hitchcock’s portrayal of women as well as the seemingly never-ending argument in horror about the genre’s relationship to women in general. Check it out, just watching the film is guaranteed to make you appreciate solid, informed filmmaking over shoddy, penis-driven filmmaking.

Triangles and Freedom in Hitchcock’s Lodger

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews