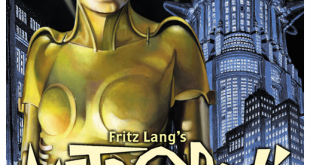

In part one, (see part 1 of Frtiz Lang’s M) we covered Fritz Lang’s immortal film M and the vampire serial killer that inspired it. But we were only breaking the skin in terms of Teutonic maniacs. This round we’ll slice a little deeper. A word of warning—I don’t recommend eating bratwurst while reading this article. Here we go!

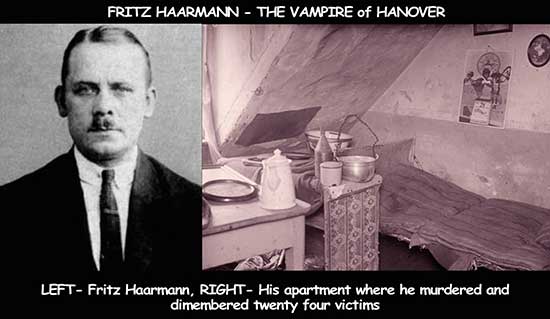

Fritz Haarmann, known as The Vampire of Hanover, started young, wracking up a history of sexual offenses by his eighteenth birthday. In 1896, he was deemed incurably damaged and committed to an asylum for life, but escaped after a few months. His attempts at living a normal life failed and he spent the periods between 1905 and 1918 drifting in and out of prison. When released in 1918, he stepped into a post war world, where a lack of food and jobs, combined with an overworked police force, created a virtual Candy Land for psychos. He became a black marketer, thief and, ironically, a paid police informant.

He used those police informant credentials to lure young men to his flat where he murdered them by biting through their tracheas before dismembering them. His killing spree continued until 1924 when he was convicted of twenty-four murders, though the actual number may be closer to seventy. He was sent to the guillotine in April of 1925. Haarmann’s story was also the basis for 1973’s Ulli Lommel/ Rainer Werner Fassbinder collaboration Tenderness of the Wolves.

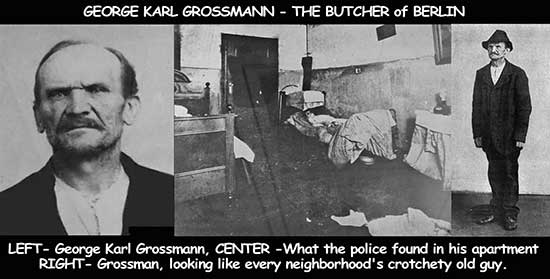

George Karl Grossman, (or George Karl Großmann) known as The Berlin Butcher, was already a convicted pedophile when he began his string of homicides stretching from 1913 to 1921. During that period he murdered between twenty-five and fifty young women, mostly prostitutes. The nickname Berlin Butcher was gruesomely accurate. Grossman made a lucrative living operating a hotdog stand, which, despite heavy meat rationing, was always well stocked.

Upon his arrest police realized Grossman had been butchering his victims and selling their flesh as bratwurst. Given his stand’s location at a busy commuter railway station Grossman likely turned thousands of hungry Berliners into involuntary cannibals. Grossmann was convicted for some of his crimes but committed suicide in prison before he could be sentenced.

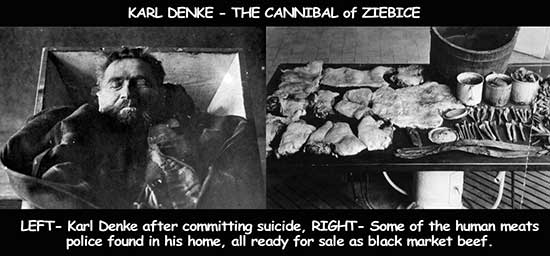

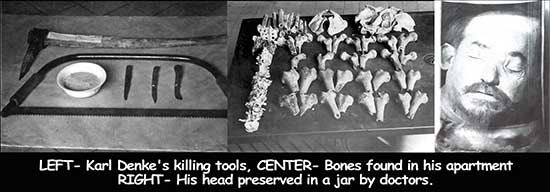

Karl Denke, called The Cannibal of Ziebice, was a former church organist who members of the congregation called “Papa.” In 1903, Denke committed the first of an estimated forty-two murders. He preyed on the homeless and destitute, correctly assuming their disappearances wouldn’t arouse interest. The Great War and the ensuing poverty created a bumper crop of potential victims. His prolific killing career went on until 1924 when one of his victims managed to escape after being struck in the skull with an axe. Investigators descended on Denke’s home where they discovered hundreds of bones along with a detailed journal of over thirty acts of murder and cannibalism.

Police also found two large tubs of pickled human meat, proving Denke’s personal journal was horribly accurate. Like Grossman, Denke not only ate his victims but also sold their pickled remains to unsuspecting customers on the black market. Also like Grossman, he committed suicide in prison before being sentenced.

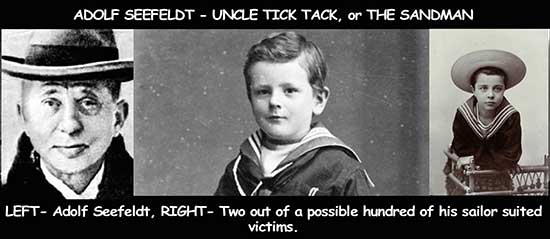

Adolf Seefeldt also known as Uncle Tick Tack confessed to twelve murders but is alleged to have poisoned over one hundred young boys. He was a religious fanatic who also claimed to be a witch, threatening to cast spells on farmers’ livestock. He also had a thing for sailor suits, which he dressed many of his victims in. Though he committed most of his crimes during the Weimar era he was captured and sentenced to death by the Nazi regime in 1936. Carl Gröpler, the same man who executed Peter Kürten and Karl Grossman, conducted his death by guillotine. Fun fact—after performing over a hundred and forty executions for Germany, Gröpler himself was executed by the occupying Soviets in 1945.

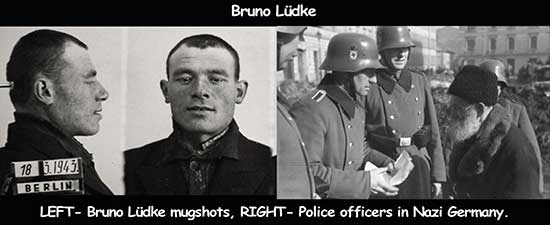

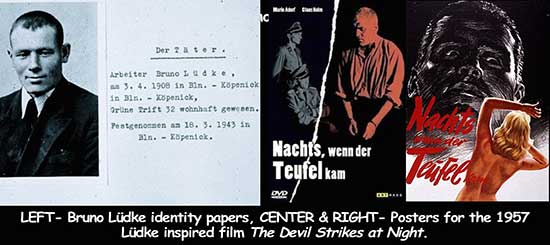

Bruno Lüdke is the list’s most controversial entry. Until recently he was believed to have committed between sixty and eighty-four serial rape and strangulation murders starting in 1920. In 1943, Lüdke was arrested near the scene of one such crime and quickly confessed. He continued confessing to a seemingly endless parade of murders, proving he was an inhuman monster. Or was he? No fingerprints or forensic evidence were ever presented, nor was any proper investigation conducted. In truth, Lüdke was a mentally deficient drifter who’d been sterilized by the Nazi government in 1939 under the “unwertes leben” (unworthy life) laws. Lüdke’s arrest and feeblemindedness provided the Nazi government with a perfect scapegoat, clearing the books on eighty unsolved murders.

On the propaganda front his crimes bolstered the concept that the former Weimar Republic was decadent and incapable of protecting its citizenry. Some German police detectives found the concept of a half-wit mass murderer eluding police for over twenty years hard to swallow. The most vocal of those detectives was quickly drafted and sent to Stalingrad, silencing any further dissent. Lüdke was never put on trial for his crimes. Instead he was shipped to an SS run facility for use in barbaric medical research. The world will never know if Lüdke was one of history’s most fiendish mass murderers or one of the millions of victims of Germany’s barbaric Nazi regime.

That was a pretty horrifying list, but remember, these are just the Weimar era’s killers that got caught. Even today, with databases and DNA evidence, it’s estimated that only a small percentage of serial murders are ever captured. The serial killer’s greatest advantage is their lack of personal connections to their victims, making traditional investigative techniques useless. This was particularly true in Weimar Germany, where starving people migrated across the country to find work. Their transient lifestyle made them easy victims that were impossible to track. Logically, there were a lot more evil bratwurst vendors lurking the streets of Germany than you see on this humble list.

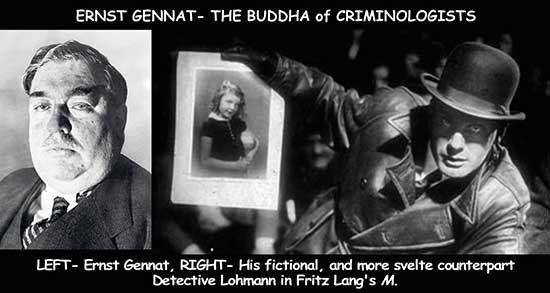

The real credit for bringing this rogues’ gallery to justice goes to one man—Detective Ernst Gennat, leader of Berlin’s Central Homicide Inspection Division. Gennat’s brilliant work made him a public figure, earning him the nickname The Buddha of Criminologists for his fine work and portly physique. Gennat inspired many fictional detectives, including Lang’s Inspector Karl Lohmann.

Berlin was one of the first cities to create a dedicated homicide squad, a division Gennat was born to run. As head of Zentralkartei für Mordsachen he invented much of what we consider modern policing. He eliminated tried and true tactics such as beating confessions out of suspects, replacing them with the use of criminal psychology and chain of evidence. His interrogation room was ghoulishly decorated with homicide photos, actual murder weapons and even an unidentified woman’s head preserved in a jar.

His tactics worked, leading to the capture of mass murderers Fritz Haarmann, George Karl Grossman and Peter Kürten. After capturing Peter Kürten he published Die Düsseldorf Sexualmorde (The Düsseldorf Sexual Murderer) in which he coined the term ‘serial killer’.

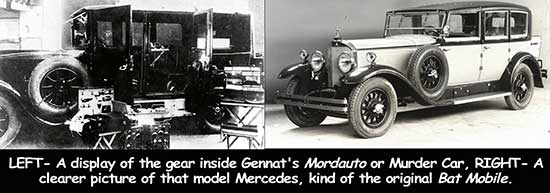

Like any good crime fighting superhero Gennat had his own custom built car he nicknamed Mordauto (Murder Car). This 1926 Mercedes Benz 16/50 was the world’s first rolling crime lab, outfitted with typewriters, a desk, rubber gloves, torches and state-of-the-art laboratory equipment. Crowds came from far and wide to get a peek at this German Bat Mobile.

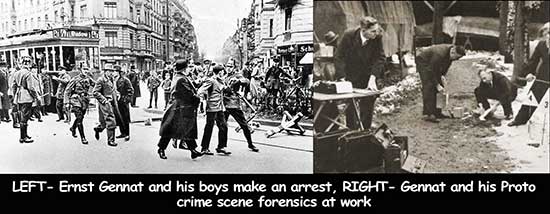

His teams of detectives were so well organized that by 1931 they’d achieved a 95% clearance rate—better than today’s average with none of the modern advantages. While much of their success could be chalked up to dogged determination and clear organization, Gennat also created databases of suspects’ behavior, fingerprints and handwriting samples, making him the first criminal profiler.

In 1938, Gennat managed another crime fighting first. Fifty years before America’s Most Wanted he went on television with Murder Coat on TV, presenting evidence in an unsolved murder to the viewing audience. It was the world’s first television manhunt. Germany had recently opened public TV rooms where locals crowded in to watch sports and propaganda (this was during the Nazi era). Despite the world only having about thirty thousand television viewers Gennat’s gamble paid off, and the killer was identified the next day.

He followed up with a second broadcast, quickly solving the murder of prostitute Lucie Plachta. It was a brilliant idea, which the government quickly put the brakes on. Apparently the Nazis didn’t like admitting publicly that murders existed in Germany—even the ones they didn’t commit.

Gennat was openly critical of his Nazi masters, but his outstanding work and reputation shielded him from any reprisals. He even managed to keep the Nazis from infiltrating his detective division. Ironically, this meant that murderers in his custody had less to fear than the average citizen.

Gennat’s career began under the Kaiser’s misrule, continuing through the wobbly Weimar Republic and into the barbaric Nazi Reich, solving crimes right up until his death in 1939. By that point the sadists and psychopaths were no longer stalking the dark alleys of Berlin—now they were running the country.

Sadly, much of Gennat’s research was forgotten after World War Two. As late as the 1970s, American police departments refused to acknowledge the existence of serial killers, convinced that murderers were always someone close to the victim. It wasn’t until the likes of Ted Bundy that law enforcement was forced to confront the ugly truth of human nature and reinvent Gennat’s work.

The Weimar Republic’s reign officially ended in 1933, replaced by Hitler’s nightmarish Third Reich. The Weimar era has been brilliantly captured in the German television series Babylon Berlin, now streaming on Netflix. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews