SYNOPSIS:

“In 1935, seasoned diplomat Robert Conway is sent to rescue a group of British nationals who find themselves in China the midst of a rebellion. Conway manages to get them all out and also to escape with his brother George and several others on the last airplane only to find that they are being flown far into the Himalayas. They eventually find themselves in Shangri-La, a Tibetan monastery in a beautiful mountain valley. It soon becomes clear that they are not there by chance and that were in fact kidnapped. Conway and his fellow travellers are keen on leaving but slowly, they all come to appreciate their new surroundings. Everyone that is except George Conway who is desperate to leave. As Robert learns the true secret of Shangri-La and his reason for being there, he is faced with having to leave in order to protect his brother who will be setting off with or without him.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Born in 1897, future filmmaker Frank Capra emigrated with his parents from Sicily at the age of six. He came to worship and propagandise the so-called ‘land of opportunity’, a land where an honest, patriotic, clean-living American boy can overcome all corruption, proving the power of the individual over the mob and those who do not conform to the best traditions of American democracy. Capra realised the ‘American Dream’ by working his way through college and starting his career at the bottom, as a film splicer and general handyman around various minor studios, ending up as a gag-writer for Hal Roach. He joined Columbia Pictures where he directed Harry Langdon in The Strong Man (1926) and Long Pants (1927). In the following seven years Capra provided rapid, hard-edged madcap comedies such as Rain And Shine (1930), Platinum Blonde (1931), American Madness (1932) and the Oscar-winner It Happened One Night (1934).

He made Barbara Stanwyck a superstar with four movies in an attempt to outdo Josef Von Sternberg in erotic exoticism: Ladies Of Leisure (1930); The Miracle Woman (1931); Forbidden (1932); and The Bitter Tea Of General Yen (1932). Then, according to Capra’s own autobiography, a strange unknown man came to him and ordered him to use his God-given talents for His purpose, and suddenly all the suggestiveness, sensuality and anarchy of his films vanished from sight. Women no longer occupied the centre, being replaced by idealistic boy-scout heroes like Gary Cooper and James Stewart. This resulted in the sequence of sanctimonious sentimental social comedies which gained the adjective Capra-esque, often referred to as Capra-Corn by more cynical viewers. Mister Deeds Goes To Town (1936), You Can’t Take It With You (1938), Mister Smith Goes To Washington (1939) and Meet John Doe (1941) glorify the ‘little man’ fighting for what’s right and decent and losing the battle until the hectic rush to achieve the happy ending.

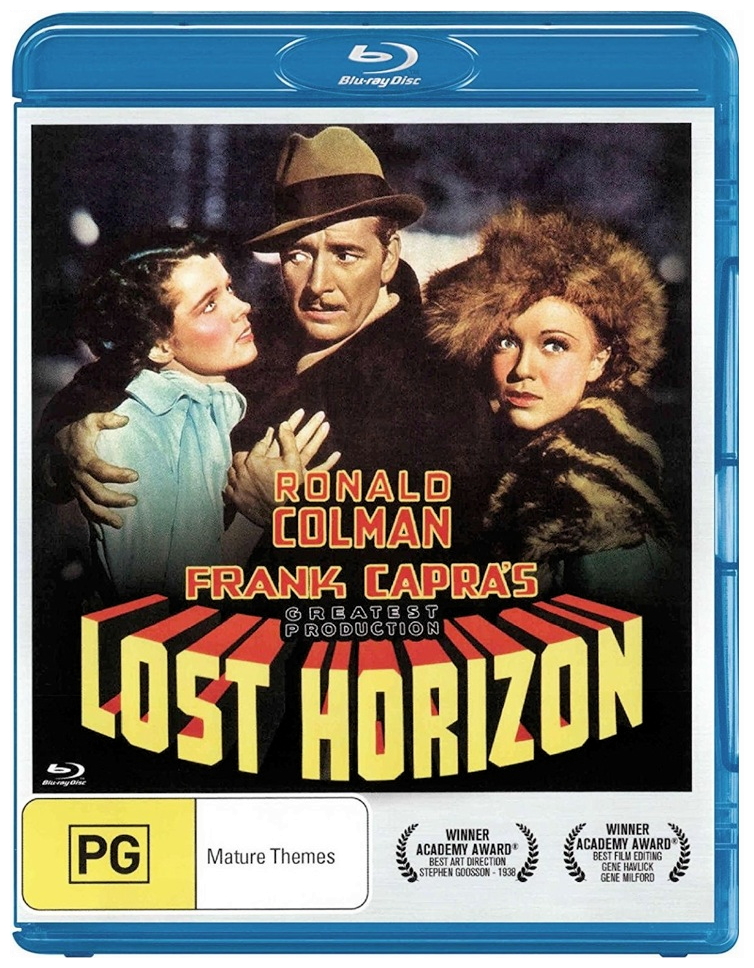

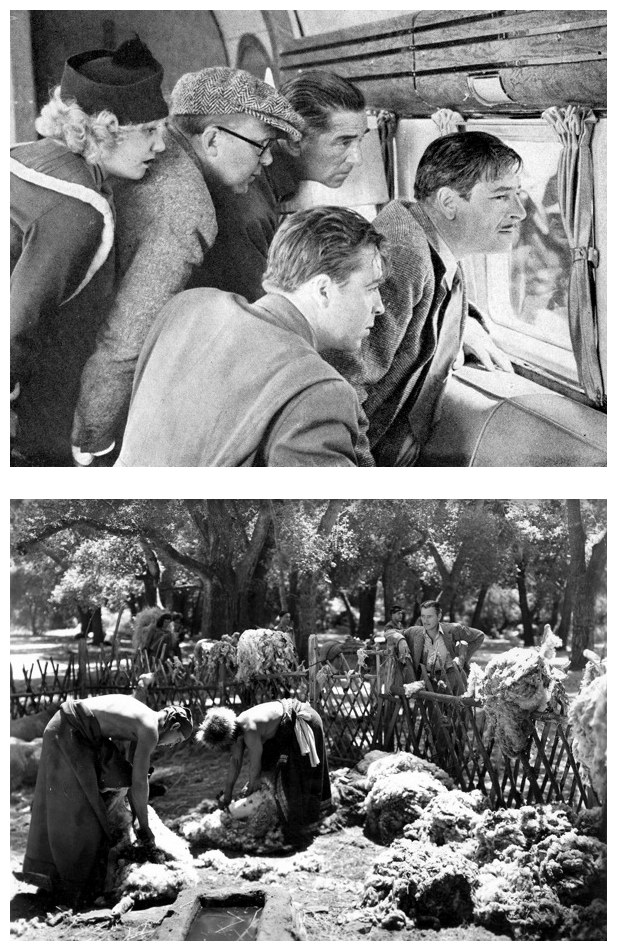

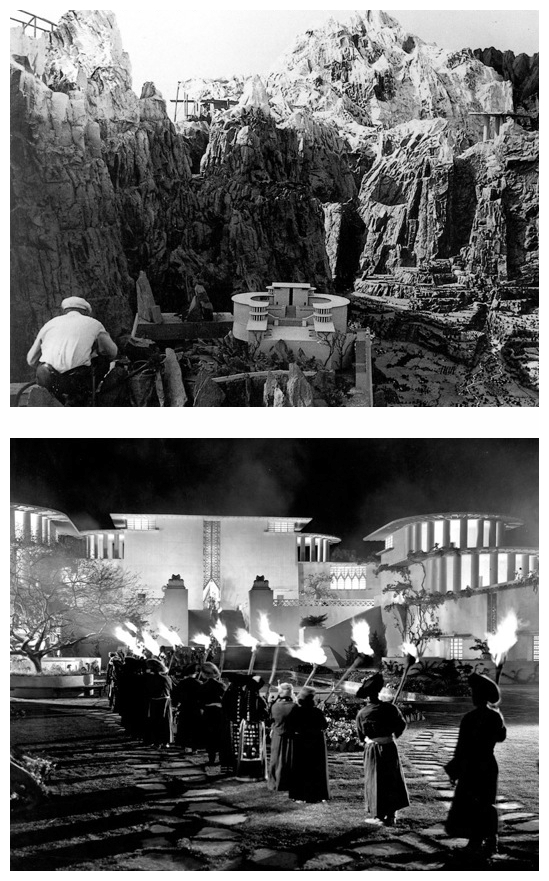

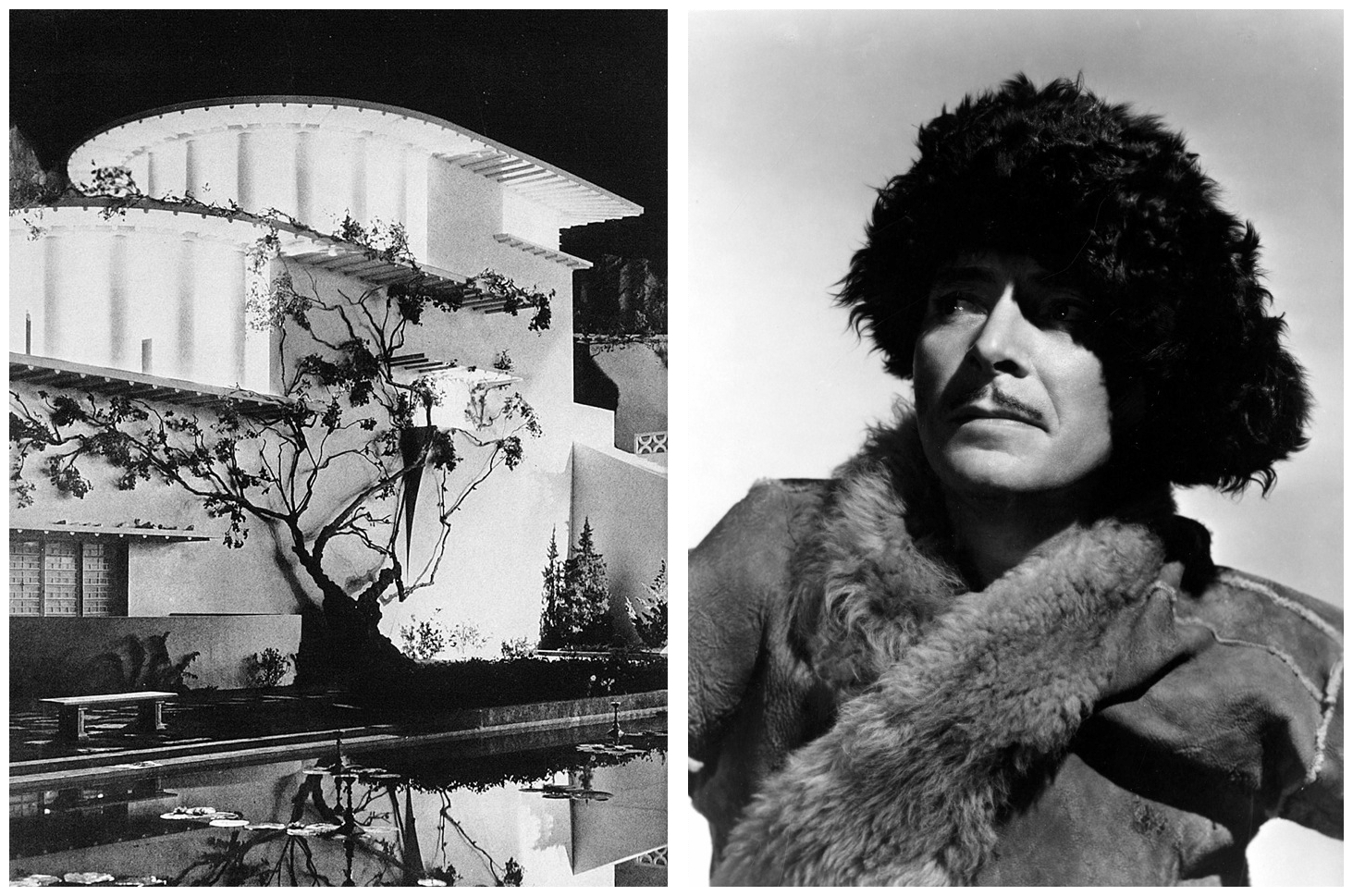

Politically naive and demagogic as they are, they have comic pace, invention and terrific performances, particularly from Jean Arthur as the sexless heroine, and Edward Arnold as the bloated plutocrat. A number of Capra’s later films have entered American folklore, and it would be invidious to criticise them with the public’s response to their message verging on the irrational, but his earlier Lost Horizon (1937) is a genuinely uplifting film, benefiting from a script by Capra’s long-term collaborator Robert Riskin, brilliantly gleaned from James Hilton‘s international bestseller about the utopian never-never-land of Shangri-La. After the spectacular success of It Happened One Night, Columbia’s fair-haired genius had enough clout to push his pet project, an expensive adaptation of Hilton’s novel, into full production. The story follows an English diplomat named Robert Conway (Ronald Colman) who helps a planeload of civilians escape death during a bloody uprising, only to find himself and his passengers abducted by the gun-wielding pilot.

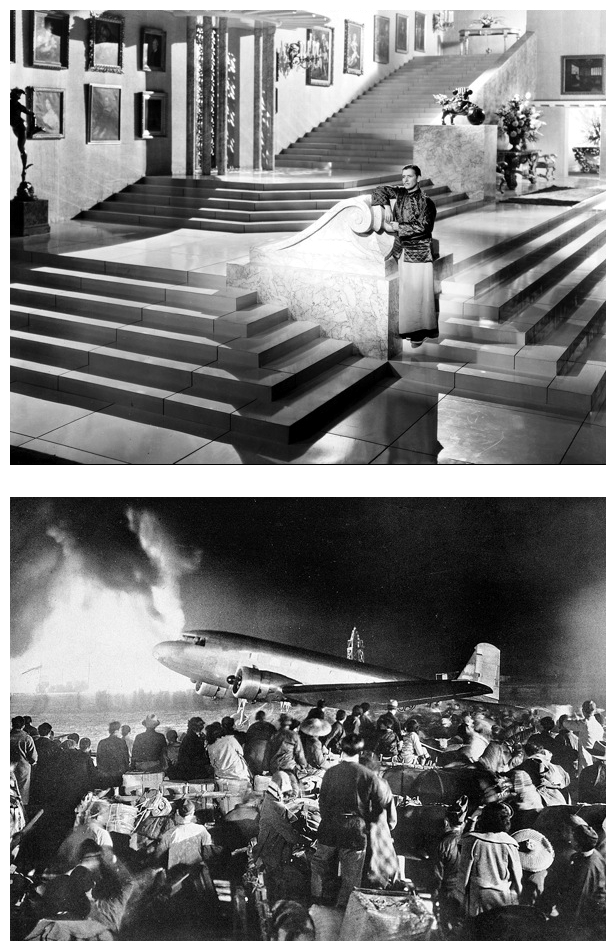

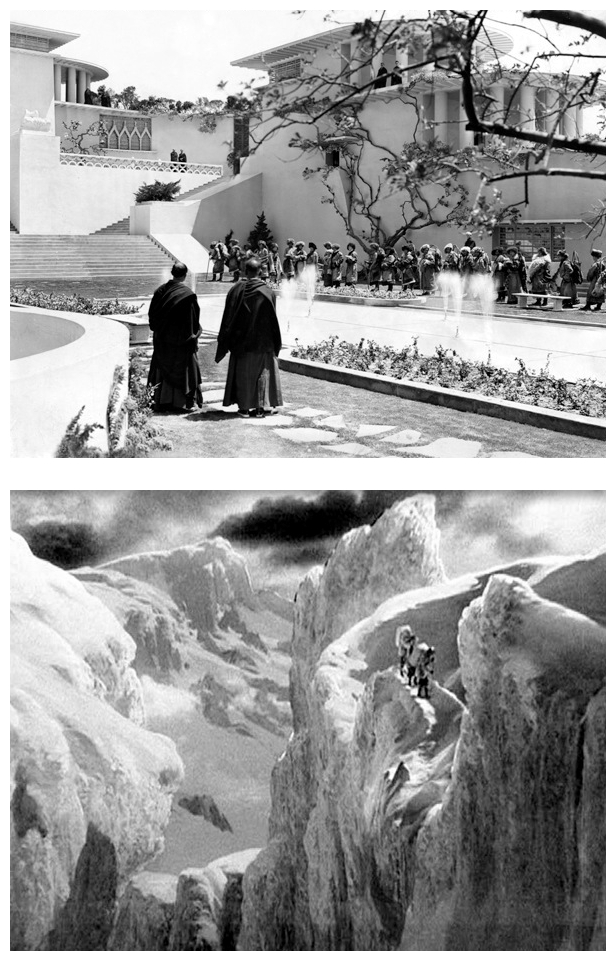

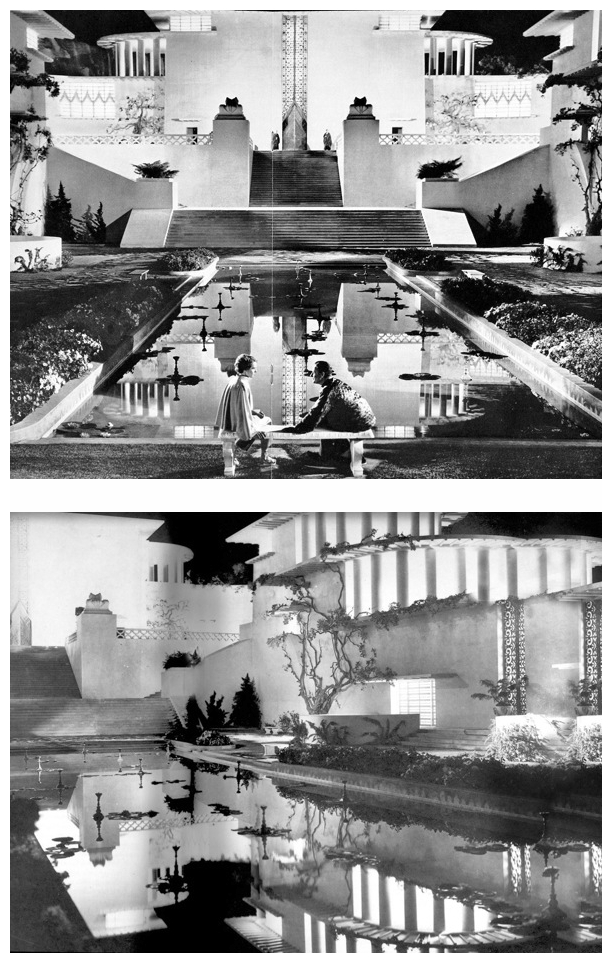

After an extended journey into uncharted snow-capped regions, the group crash-lands with little hope of rescue from the outside world. Miraculously, Conway and his people are escorted to a fantastic community known as Shangri-La. An elderly wise-man and leader known as the High Lama (Sam Jaffe), who is fearful that humanity is destroying itself, has been collecting the great artistic accomplishments of mankind to preserve them forever in this isolated paradise. Conway learns that he has been personally selected to continue the High Lama’s noble work after the old leader’s death, but Robert’s restless brother George Conway (John Howard) is determined to leave. An ill-advised escape with one of the locals results in a bizarre and terrifying event, proving the High Lama’s fantastic warnings to be true. Against all odds, Conway braves the elements and manages to find his way back to Shangri-La, fulfilling his unique destiny.

At the time of its release, some Hollywood critics were unkind, and not just because of the hard-to-swallow fantasy content of Hilton’s utopian premise. This supposed classic has dated a little, the sentimental elements seem marshmallowy nowadays, and the philosophy of the ever-youthful inhabitants of utopian Shangri-La seems banal. But the story of the discovery of the lost valley in the Himalayas still grips, and Ronald Colman‘s struggling return through the snow to the hidden city still moves. “Nothing happens once they reach Shangri-La!” or “This place is such a paradise, there’s no conflict in the story!” Unless, of course, you consider choosing between a glorious humanist dream, and the harsh realities of war-torn 1937 to be a trivial mental exercise. How about the decision to abandon true love in favour of lonely, pointless civic duty? Then there’s the primal obligation of brotherly concern to consider, along with the purely physical, ultra-daunting challenge of risking life and limb in freezing weather upon massive mountains and snowy ravines.

Clearly, Capra considered these and other plot elements dramatically satisfying enough to sustain viewer interest over the long haul. Shangri-La may be able to provide its inhabitants with eternal youth, but Capra’s classic has dated badly. The most exciting scenes are those before idealist Ronald Colman and friends reach the utopia in the Himalayas and when Colman and friends finally begin to climb down. The time the characters spend in this land where people are healthy, exist in harmony, and live for two hundred years is dull by comparison. Who wants to watch people vacation at a spa? Colman, with his voice at its most melodious, has a couple of interesting scenes with Sam Jaffe as Shangri-La’s High Lama, who wants Colman to succeed him, and Colman and Jane Wyatt have an appealing mature relationship. That being said, there is a peculiar, possibly unintentional undercurrent of compromised morality in Hilton’s fountain-of-youth paradise, beginning with the semi-savage abduction itself. It might be harsh to categorise Chang (H.B. Warner) as an out-and-out liar, but he’s certainly a master of half-truths and personable deception.

Maria’s (Margo, real name Maria Margarita Guadalupe Teresa Estella Castilla Bolado y O’Donnell) spooky age-regression suggests that Chang and the High Lama were telling the truth all along. Yet why would this apparently rational young woman rather kill herself than live another day in ‘paradise’? Clearly not everyone in the Valley of the New Moon is as blissfully content as Shangri-La’s leaders would have us believe. Lost Horizon was always so much ‘flapdoodle’ anyway, but the wish-fulfilment comfort zone provided by such a utopian dream never fails to soothe decent people looking for easy answers, or at least a brief respite in an imaginary land without strife or conflict, a living death for some, eternal bliss and security for others. Please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through Hollywood’s twisted interpretation of mysterious Tibetan lifestyle choices for…Horror News! Toodles!

Lost Horizon (1937)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews