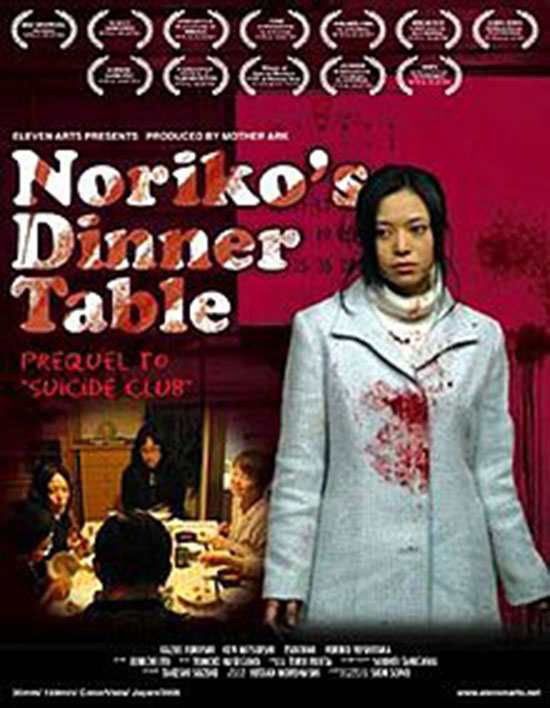

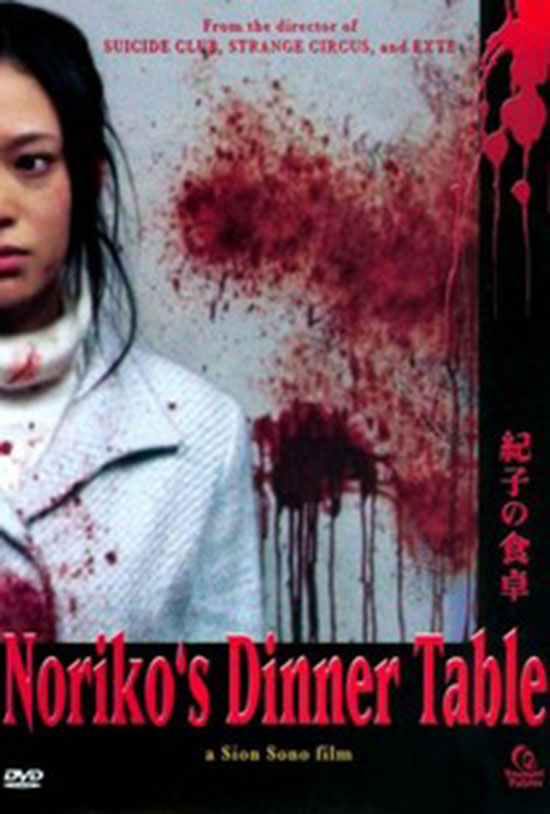

SYNOPSIS:

A teenager called Noriko Shimabara runs away from her family in Tokoyama, to meet Kumiko, the leader of an Internet BBS, Haikyo.com. She becomes involved with Kumiko’s “family circle”, which grows darker after the mass suicide of 54 high school girls.

REVIEW:

Japan has a long history with suicide. One of the more notorious acts among the samurai was the practice of Seppuku, where a warrior chose ritualistic self-disembowelment before allowing an enemy the satisfaction. The kamikaze pilots of WWII were weaponized suicide–the most effective way to destroy one’s enemy was to destroy oneself in the process. In more recent years, the country holds one of the highest suicide rates in the world, a study in 2014 averaging 70 people per day, many being middle-aged businessmen. It is even home to Aokigahara, the famous Suicide Forest, which remains the most popular suicide destination in the world, enough that signs are posted along the trails imploring the reader to think of their families and seek counseling. It’s not as if Japan has an inordinate fixation with suicide or are more depressed nationwide than any other country (the US’s numbers aren’t so great either). It’s more like a cultural openness in accepting suicide as a reasonable option when everything else goes wrong.

Suicide Club is one of the more notorious films to come out of the Asian extreme movement in the early 2000s. Many of us are familiar with the iconic image of a line of schoolgirls jumping gleefully into the path of an oncoming train. Unfortunately, the 2002 film is largely remembered for little else aside from that shocker of an opening, due to a meandering plot that suffered from more than a few holes. Four years later, writer/director Sion Sono would return to attempt to fill in those gaps with Noriko’s Dinner Table, a prequel that would not only get into the backstory of the Suicide Club, but also explore the depths of loneliness that would drive someone to take the leap.

Noriko is a classic indie film teen heroine: seventeen and morose and restless living with her family in their pretty but boring small town. She finds her tribe among the fellow members of a website called Haiyko.com, best described as a Reddit-esque series of threads where people post their personal thoughts and connect with others around the country. Noriko dreams of running away to Tokyo to be with her internet friends and beginning her life again as her online persona “Mitsuko.”

After one of many fights with her father over where she will go to college, she packs her bags and hops a bus to Tokyo with no plans other than to get there. She reaches out to her internet friend and moderator of Haiyko.com, known as Ueno Station #54, and requests to meet her in person. Ueno reveals herself to be Kumiko, a friendly girl who has brought her whole family along for the meet-up, and all instantly accept “Mitsuko” with open arms.

Noriko spends the day with Kumiko’s family, basically being the postcard of an ideal family. But things seem suspiciously picturesque, a little too good to be true. It is revealed piece by piece that Kumiko runs a service known as family rental, where performers are hired to act in the roles of lost loved ones, sort of like emotional prostitution. Abandoned grandparents, mourning widowers—whatever your sad story, Kumiko can deliver a perfect reproduction of it. Noriko finds she has a natural gift for the work and, under Kumiko’s guidance, begins her new life as Mitsuko.

Six months later, 54 schoolgirls leap to their deaths on the train tracks.

That summary only makes up a fraction of this rather layered plot, as the movie is told in non-linear chapters divided by shifting points of view. But Kumiko’s family rental business and its tangential relation to the so-called Suicide Club is the centerpiece to this very sad, strange, captivating film. Noriko’s Dinner Table explores loneliness in all its many guises: a teenaged girl feeling trapped and misunderstood, a father who realizes that his children are strangers to him, a mother who feels she has failed at keeping her family together. The performance of the happy family of actors juxtaposed with the mediocre unhappiness of the real family is devastatingly tragic, and a cycle that seems to invert and repeat throughout the film. Moving with much the same pace and language as a novel, it manages to be told largely through expressive visuals while also having voice-over narration throughout. On the whole, the language in the narration is lovely (especially Noriko’s chapter) and often necessary to fully explain the details of the plot, but the device begins to wear thin by the fourth act.

Yes, fourth act. One of the film’s biggest flaws is that it’s about a half-hour too long and tends to milk some of its explosively emotional moments for maximum feels and/or poetic potency, especially in that last act. For me, though, I responded more to the quieter moments throughout than the big outbursts at the climax. It was those small painful scenes that felt familiar to my own experience, feelings I can remember from some of my loneliest times.

There are many reasons to want to take your own life, but it seems the most common reasons come down to loneliness–being a failure, being left behind, being ignored. We are genetically social creatures and without that social bond, we lose an essential part of ourselves. But often in our need to fill a role—a loving wife, a supportive father, a happy daughter, a sisterly best friend—in our desperation to not be alone, we end up losing ourselves. The recurring line of “Are you connected to yourself?” is the simplest summation of the film’s main theme–that in this desert of impending doom called life, in the end all you have is yourself. And if you don’t know yourself, what do you have?

This is a horror movie in the same way Melancholia is a horror movie—a film that shows some terrifying things but by the end leaves you with all the big questions and a slight stomachache. The kind of horror that doesn’t scare you so much as it severely bums you out.

I would highly recommend Noriko’s Dinner Table for the sheer experience of it. The onslaught of depression aside, it tells an engrossing story in a stylistically interesting way. And I believe that every now and then, you should allow a film to get in your head and beat your emotions bloody for an hour or two (or nearly three, in Noriko’s case). It’s good for the soul, gives the brain some exercise, and perhaps makes you appreciate your life a little bit more. But viewer discretion advised: make sure you’re well rested and have a substantial meal beforehand, and maybe have a nice dog to pet after the credits roll. You’re going to need it.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews