SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Doctor James Xavier is a world renowned scientist experimenting with human eyesight. He devises a drug, that when applied to the eyes, enables the user to see beyond the normal realm of our sight (ultraviolet rays etc.) it also gives the user the power to see through objects. Xavier tests this drug on himself, when his funding is cut off. As he continues to test the drug on himself, Xavier begins to see, not only through walls and clothes, but through the very fabric of reality!” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

During the late fifties, horror cinema was temporarily abandoned by the larger studios, replaced mostly by low-budget black-and-white films about monsters. At the beginning of the sixties the budgets were lower than ever, but everything else was changing. As monsters flew out the window, doomed neurotics were plodding hauntedly through the door. The day of the Gothic Costume Drama had arrived, and its prophet was a brisk young fellow named Roger Corman. The Gothic was a familiar element in genre cinema from the beginning but, oddly enough, no matter how medieval the plots, most such Gothics had been set in more-or-less contemporary times. Then Roger, with his writers Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont, discovered Edgar Allan Poe.

The first, if not the best, of Roger’s Poe adaptations was The Fall Of The House Of Usher (1960). Like the subsequent adaptations, it was designed by Daniel Haller (who later became a fair director himself) and photographed by Floyd Crosby in Pathecolor. Roger abandoned his usual speedy cutting and vigour for a hypnotic, rather ponderous style which seems to float lethargically through nightmares that are not so much terrifying as excruciatingly claustrophobic. Yet audiences loved them, and a number of follow-ups were produced, including The Pit And The Pendulum (1961), The Premature Burial (1962), Tales Of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), The Terror (1963), The Tomb Of Ligeia (1964) and The Masque Of The Red Death (1964).

The first, if not the best, of Roger’s Poe adaptations was The Fall Of The House Of Usher (1960). Like the subsequent adaptations, it was designed by Daniel Haller (who later became a fair director himself) and photographed by Floyd Crosby in Pathecolor. Roger abandoned his usual speedy cutting and vigour for a hypnotic, rather ponderous style which seems to float lethargically through nightmares that are not so much terrifying as excruciatingly claustrophobic. Yet audiences loved them, and a number of follow-ups were produced, including The Pit And The Pendulum (1961), The Premature Burial (1962), Tales Of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), The Terror (1963), The Tomb Of Ligeia (1964) and The Masque Of The Red Death (1964).

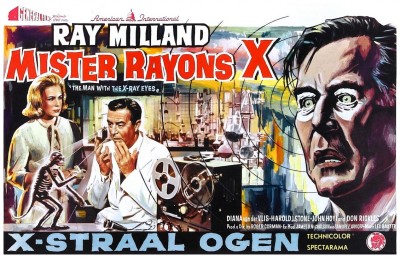

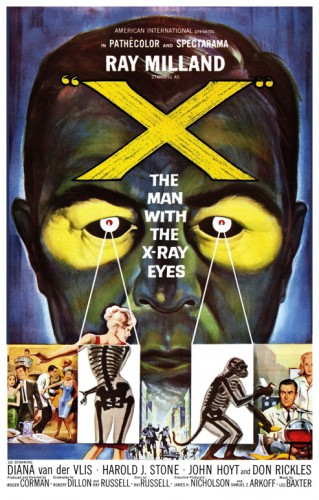

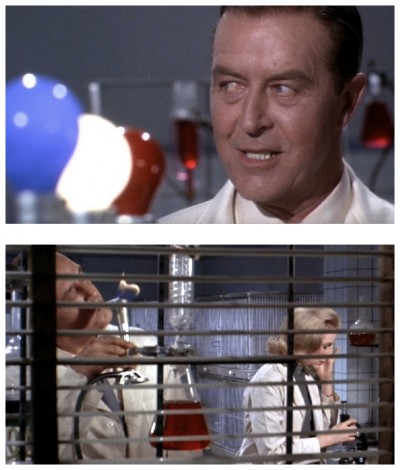

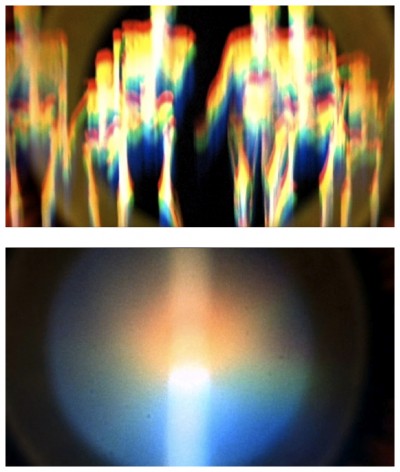

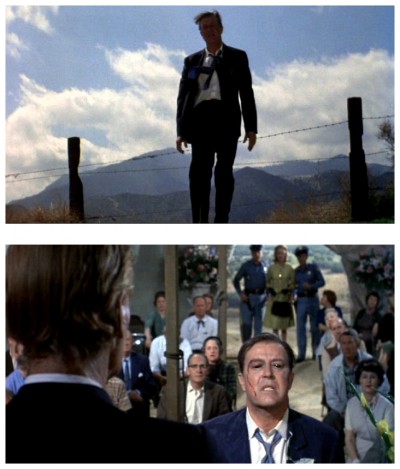

Roger had not entirely abandoned science fiction while all this was going on. One of his best and most modest films was X The Man With The X-Ray Eyes (1963) starring Ray Milland as Doctor Xavier, who is trying to create a serum that will enable him to see through solid opaque materials. His reasons are purely altruistic – he believes that such an ability would greatly improve medical diagnosis – but naturally everything goes wrong. No sooner does he start experimenting with the serum on his own eyes, than he gets into an argument with a colleague (Harold J. Stone) and accidentally knocks him out of a window, killing him. The serum works all too well, and his sight into the horrors that go on inside perfectly ordinary-seeming people drives him close to madness. Nor does it end there. Soon his vision is penetrating to the heart of the cosmos – the deepest mysteries of all things. This is all cheaply symbolised visually by using black contact lenses, which have the paradoxical effects of making him appear sightless.

Roger had not entirely abandoned science fiction while all this was going on. One of his best and most modest films was X The Man With The X-Ray Eyes (1963) starring Ray Milland as Doctor Xavier, who is trying to create a serum that will enable him to see through solid opaque materials. His reasons are purely altruistic – he believes that such an ability would greatly improve medical diagnosis – but naturally everything goes wrong. No sooner does he start experimenting with the serum on his own eyes, than he gets into an argument with a colleague (Harold J. Stone) and accidentally knocks him out of a window, killing him. The serum works all too well, and his sight into the horrors that go on inside perfectly ordinary-seeming people drives him close to madness. Nor does it end there. Soon his vision is penetrating to the heart of the cosmos – the deepest mysteries of all things. This is all cheaply symbolised visually by using black contact lenses, which have the paradoxical effects of making him appear sightless.

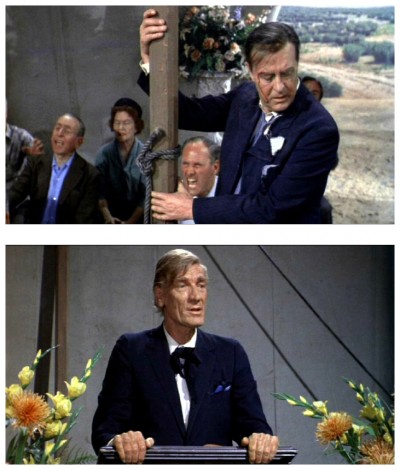

Forced to go on the run from the police, Xavier hides out in a small-time carnival where his powers are exploited by a slimy sideshow manager played by Don Rickles – future Mister Potato-Head in Toy Story (1995) – who gives a splendidly nasty performance. Xavier’s old girlfriend Diane (Diana Van Der Vlis) catches up with him and together they go to Las Vegas where, for a time, he has fun breaking the bank in a casino before his unusual winning streak attracts the attention of the police. Pursued by them into the desert he crashes his car and then stumbles into the tent of an evangelical preacher (John Dierkes). Xavier’s eyes have now become like large black discs, he stares into the air and announces, “I’ve come to tell you what I see! There are great darknesses, farther than time itself, and beyond the darkness a light that glows and changes and, in the centre of the universe, the eye that sees us all!” The preacher helpfully replies, “You have seen sin and the devil, but the Lord has told us what to do about it. Said Matthew in Chapter Five, if thine eye offend thee, pluck it out!”

Forced to go on the run from the police, Xavier hides out in a small-time carnival where his powers are exploited by a slimy sideshow manager played by Don Rickles – future Mister Potato-Head in Toy Story (1995) – who gives a splendidly nasty performance. Xavier’s old girlfriend Diane (Diana Van Der Vlis) catches up with him and together they go to Las Vegas where, for a time, he has fun breaking the bank in a casino before his unusual winning streak attracts the attention of the police. Pursued by them into the desert he crashes his car and then stumbles into the tent of an evangelical preacher (John Dierkes). Xavier’s eyes have now become like large black discs, he stares into the air and announces, “I’ve come to tell you what I see! There are great darknesses, farther than time itself, and beyond the darkness a light that glows and changes and, in the centre of the universe, the eye that sees us all!” The preacher helpfully replies, “You have seen sin and the devil, but the Lord has told us what to do about it. Said Matthew in Chapter Five, if thine eye offend thee, pluck it out!”

Xavier does just that, and there is a brief shot of him looking like old King Lear with gaping eye-sockets and blood running down his cheeks. It’s all done in the best possible taste. Directed by Roger for American International Pictures from a screenplay by Robert Dillon and Ray Russell, the film is mainly interesting because of its visual inventiveness, though Roger’s usual lack of a sufficient budget prevented the possible permutations of the idea being fully realised. Ray Milland makes a good lead, a character who’s not entirely sympathetic, and it’s worth keeping an eye out (ow!) for Corman regulars Dick Miller, Jonathan Haze, Barboura Morris, John Hoyt and, in his final role, Morris Ankrum. The film’s message is the same one that has echoed down science fiction cinema since the beginning, except in this case it’s not so much ‘There are some things Man was not meant to know,’ as ‘There are some things Man was not meant to see.’

Xavier does just that, and there is a brief shot of him looking like old King Lear with gaping eye-sockets and blood running down his cheeks. It’s all done in the best possible taste. Directed by Roger for American International Pictures from a screenplay by Robert Dillon and Ray Russell, the film is mainly interesting because of its visual inventiveness, though Roger’s usual lack of a sufficient budget prevented the possible permutations of the idea being fully realised. Ray Milland makes a good lead, a character who’s not entirely sympathetic, and it’s worth keeping an eye out (ow!) for Corman regulars Dick Miller, Jonathan Haze, Barboura Morris, John Hoyt and, in his final role, Morris Ankrum. The film’s message is the same one that has echoed down science fiction cinema since the beginning, except in this case it’s not so much ‘There are some things Man was not meant to know,’ as ‘There are some things Man was not meant to see.’

Rumour has it that in the original ending of X The Man With The X-Ray Eyes, after Xavier plucks his eyes out, he looks into the camera with his bloodied sockets and screams, “I can still see!” Supposedly, Roger chose to freeze the frame before the line, because the scene was thought to be too frightening, which is a little like removing a joke from a comedy because it was too funny. However, Roger said he was dissatisfied with the results and retained the original script’s ending: “I feel it was an opportunity that was slightly missed. The original idea to do a picture about a man who could see through objects was Jim Nicholson‘s and then the development of the basic idea was mine and Ray Russell‘s. I almost didn’t do the picture for two reasons. One, I felt the script had not turned out as well as I had expected, and two, the more I got into it the more I felt we were going to be heavily dependent on the special effects.”

Rumour has it that in the original ending of X The Man With The X-Ray Eyes, after Xavier plucks his eyes out, he looks into the camera with his bloodied sockets and screams, “I can still see!” Supposedly, Roger chose to freeze the frame before the line, because the scene was thought to be too frightening, which is a little like removing a joke from a comedy because it was too funny. However, Roger said he was dissatisfied with the results and retained the original script’s ending: “I feel it was an opportunity that was slightly missed. The original idea to do a picture about a man who could see through objects was Jim Nicholson‘s and then the development of the basic idea was mine and Ray Russell‘s. I almost didn’t do the picture for two reasons. One, I felt the script had not turned out as well as I had expected, and two, the more I got into it the more I felt we were going to be heavily dependent on the special effects.”

“The picture was shot in three weeks on a medium-low budget and I felt we were not going to be able to photograph what Xavier could see, and that the audience would be cheated. The picture turned out reasonably well but I think, when finished, it did suffer from that. The effects just weren’t there. We did the best we could. To show a man seeing through a building I photographed buildings that were in various stages of construction, on the basis he could see through the outer skin, which was a reasonable cheat, but it was still a cheat.” One rumour that can be confirmed is the film originally had a five-minute prologue about the human senses. For some unknown reason, after the initial release of the film, the prologue was removed from each and every print, reducing the running time to seventy-nine minutes.

“The picture was shot in three weeks on a medium-low budget and I felt we were not going to be able to photograph what Xavier could see, and that the audience would be cheated. The picture turned out reasonably well but I think, when finished, it did suffer from that. The effects just weren’t there. We did the best we could. To show a man seeing through a building I photographed buildings that were in various stages of construction, on the basis he could see through the outer skin, which was a reasonable cheat, but it was still a cheat.” One rumour that can be confirmed is the film originally had a five-minute prologue about the human senses. For some unknown reason, after the initial release of the film, the prologue was removed from each and every print, reducing the running time to seventy-nine minutes.

Roger Corman‘s own genius is not unlike Doctor Xavier’s in the film. He can see right through the fat of conventional horror cliches to the lethal metaphor that lies hidden beneath. He makes good horror films because they all have something to say, beyond the immediate nightmares they so melodramatically describe. And it’s with this thought in mind I’ll bid you a good night and pleasant dreams, but not before profusely thanking Mark Thomas McGee – author of Roger Corman The Best Of The Cheap Acts (McFarland Press 1988) – for his invaluable assistance in researching this article. I’m convinced you’ll show your gratitude too, by popping in again next week when I dig-up another terror from beyond the bottom of the garden path for…Horror News! Toodles!

Roger Corman‘s own genius is not unlike Doctor Xavier’s in the film. He can see right through the fat of conventional horror cliches to the lethal metaphor that lies hidden beneath. He makes good horror films because they all have something to say, beyond the immediate nightmares they so melodramatically describe. And it’s with this thought in mind I’ll bid you a good night and pleasant dreams, but not before profusely thanking Mark Thomas McGee – author of Roger Corman The Best Of The Cheap Acts (McFarland Press 1988) – for his invaluable assistance in researching this article. I’m convinced you’ll show your gratitude too, by popping in again next week when I dig-up another terror from beyond the bottom of the garden path for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews