SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

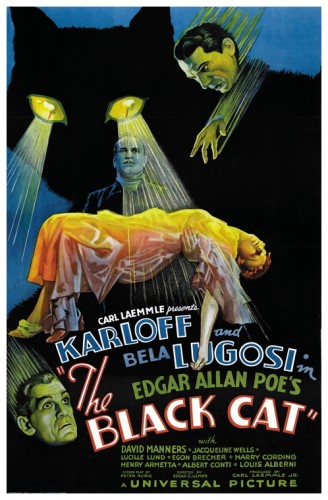

“Honeymooning in Hungary, Joan and Peter Allison share their train compartment with Doctor Vitus Werdegast, a courtly but tragic man who is returning to the remains of the town he defended before becoming a prisoner of war for fifteen years. When their hotel-bound bus crashes in a mountain storm and Joan is injured, the travelers seek refuge in the home, built fortress-like upon the site of a bloody battlefield, of famed architect Hjalmar Poelzig. There, cat-phobic Werdegast learns his wife’s fate, grieves for his lost daughter, and must play a game of chess for Allison’s life.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

In 1928, Carl Laemmle Senior made his son, Carl Laemmle Junior, head of Universal Pictures as a 21st birthday present. Woo hoo! Universal already had a reputation for nepotism – at one point, seventy of Carl Senior’s relatives were supposedly on the payroll. Many of them were nephews, resulting in Carl Senior being known around the studios as Uncle Carl. If you’re wondering how to pronounce the surname, Ogden Nash once rhymed, “Uncle Carl Laemmle, has a very large faemmle.” To his credit, Carl Junior persuaded his father to bring Universal up-to-date, buying theatres, building cinemas, converting to sound films, and making several forays into high-quality production. Carl Junior also created a successful niche for the studio by initiating a long-running franchise of monster movies, among them Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932) starring Boris Karloff, and Dracula (1931) starring Bela Lugosi.

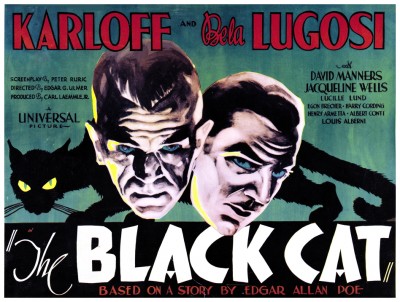

Each player had made considerable impact in his role, why not combine both in a single film? Why not endow this film with a high order of horror ‘class’ by drawing it from the works of Edgar Allan Poe? Poe had not been neglected by early filmmakers. D.W. Griffith in particular used Poe’s life and works as the basis for several films in the silent era. In fact, a year before Universal green-lit The Black Cat (1934), a German film entitled Terrible Stories (1933) – three interconnected episodes in the capture of a madman – used the same Poe story, sticking fairly close to the account of a lady-killer who inadvertently seals a cat in the alcove into which he bricks up his wife’s body (the animal’s cries betray him to the police).

Each player had made considerable impact in his role, why not combine both in a single film? Why not endow this film with a high order of horror ‘class’ by drawing it from the works of Edgar Allan Poe? Poe had not been neglected by early filmmakers. D.W. Griffith in particular used Poe’s life and works as the basis for several films in the silent era. In fact, a year before Universal green-lit The Black Cat (1934), a German film entitled Terrible Stories (1933) – three interconnected episodes in the capture of a madman – used the same Poe story, sticking fairly close to the account of a lady-killer who inadvertently seals a cat in the alcove into which he bricks up his wife’s body (the animal’s cries betray him to the police).

Carl Junior was very aware of production work in Europe, indeed he hired a European-trained young Austrian by the name of Edgar G. Ulmer, then only thirty years old, as director to ensure that his film would have the proper Germanic Gothic atmosphere. Ulmer, who had assisted the great German director of Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (1926), F.W. Murnau, succeeded all too well. The story, from a treatment by Ulmer and Peter Ruric supposedly based on the Poe classic, made only incidental use of the story’s theme, dismissing Poe almost entirely, for a completely original story of devil worship and black mass orgies in the Balkans. And yet, even though violating the letter and spirit of Poe, The Black Cat is a fascinating dark landmark in the genre cinema. Never before were the rituals of witchcraft more completely presented, even though the participants appear extremely civilised throughout, never abandoning their decorum or mussing their formal clothes, yet one can fully accept the proceedings as aesthetic, ritualistic Satanic worship, where no clothes need be shed.

Carl Junior was very aware of production work in Europe, indeed he hired a European-trained young Austrian by the name of Edgar G. Ulmer, then only thirty years old, as director to ensure that his film would have the proper Germanic Gothic atmosphere. Ulmer, who had assisted the great German director of Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (1926), F.W. Murnau, succeeded all too well. The story, from a treatment by Ulmer and Peter Ruric supposedly based on the Poe classic, made only incidental use of the story’s theme, dismissing Poe almost entirely, for a completely original story of devil worship and black mass orgies in the Balkans. And yet, even though violating the letter and spirit of Poe, The Black Cat is a fascinating dark landmark in the genre cinema. Never before were the rituals of witchcraft more completely presented, even though the participants appear extremely civilised throughout, never abandoning their decorum or mussing their formal clothes, yet one can fully accept the proceedings as aesthetic, ritualistic Satanic worship, where no clothes need be shed.

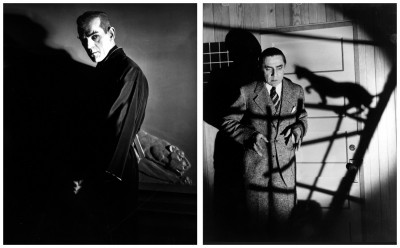

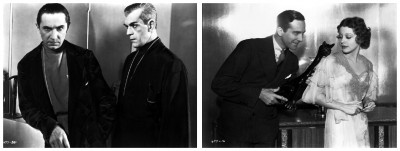

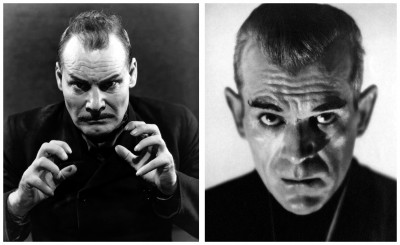

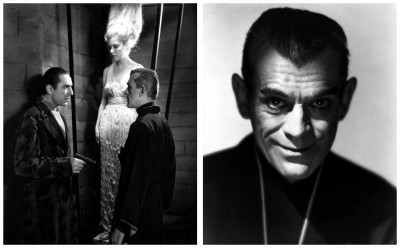

Never has Karloff had a more suavely evil role, sensuous and demonic, with his hairline pointed down the centre of his forehead to make him appear like the devil himself. Rarely was Lugosi to enjoy playing such a sympathetic character although, by the end, he too is driven completely mad, caught-up in the grotesque spirit of the plot. The struggle is essentially one of good science versus evil science, for engineer Hjalmar Poelzig (Boris Karloff) in his strange fortress laboratory, is both scientist and modern necromancer, as well as being a devil-worshiping necrophiliac. His struggle with doctor Vitus Werdegast (Bela Lugosi) takes place in an overcast middle-European mountain countryside that has a haunted and oppressive atmosphere all its own. This dark and spreading evil, ingrained in the spirit of the film and culminating in actual Satanic worship, makes The Black Cat a must-see for any serious fan.

Never has Karloff had a more suavely evil role, sensuous and demonic, with his hairline pointed down the centre of his forehead to make him appear like the devil himself. Rarely was Lugosi to enjoy playing such a sympathetic character although, by the end, he too is driven completely mad, caught-up in the grotesque spirit of the plot. The struggle is essentially one of good science versus evil science, for engineer Hjalmar Poelzig (Boris Karloff) in his strange fortress laboratory, is both scientist and modern necromancer, as well as being a devil-worshiping necrophiliac. His struggle with doctor Vitus Werdegast (Bela Lugosi) takes place in an overcast middle-European mountain countryside that has a haunted and oppressive atmosphere all its own. This dark and spreading evil, ingrained in the spirit of the film and culminating in actual Satanic worship, makes The Black Cat a must-see for any serious fan.

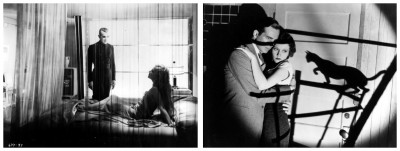

While on their honeymoon in Hungary, newlyweds Peter (David Manners) and Joan (Julie Bishop) learn that due to a mix-up, they must share a train compartment with Vitus Werdegast, a Hungarian psychiatrist and his manservant Thamal (Harry Cording). On the train, the doctor explains that he is traveling to see an old friend, Hjalmar Poelzig, an Austrian architect. Eighteen years before, Werdegast went to war, never to see his wife again, and has spent the last fifteen years in an infamous prison camp. Later they all share a bus which soon crashes on the desolate rain-swept road. Joan is injured, so Werdegast, Thamal and Peter take her to Poelzig’s ultra-modern Bauhaus house, built upon the ruins of Fort Marmorus, which Poelzig commanded during the war. Werdegast treats Joan’s injury, administering the hallucinogen hyoscine, causing her to behave erratically. Werdegast accuses Poelzig of betraying the fort during the war to the Russians, resulting in the deaths of thousands. He also accuses Poelzig of stealing his wife Karen while he was in prison.

While on their honeymoon in Hungary, newlyweds Peter (David Manners) and Joan (Julie Bishop) learn that due to a mix-up, they must share a train compartment with Vitus Werdegast, a Hungarian psychiatrist and his manservant Thamal (Harry Cording). On the train, the doctor explains that he is traveling to see an old friend, Hjalmar Poelzig, an Austrian architect. Eighteen years before, Werdegast went to war, never to see his wife again, and has spent the last fifteen years in an infamous prison camp. Later they all share a bus which soon crashes on the desolate rain-swept road. Joan is injured, so Werdegast, Thamal and Peter take her to Poelzig’s ultra-modern Bauhaus house, built upon the ruins of Fort Marmorus, which Poelzig commanded during the war. Werdegast treats Joan’s injury, administering the hallucinogen hyoscine, causing her to behave erratically. Werdegast accuses Poelzig of betraying the fort during the war to the Russians, resulting in the deaths of thousands. He also accuses Poelzig of stealing his wife Karen while he was in prison.

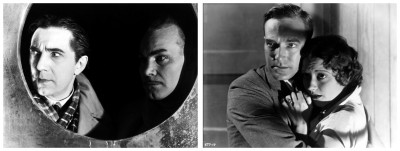

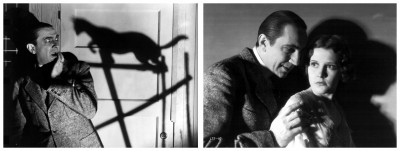

Earlier in the movie, Werdegast kills Poelzig’s black cat but Poelzig, who keeps dead women on display in glass cases, carries a black cat around the house with him while he oversees the women’s apparently sleeping forms. This is about as close as we get to the original Poe story, which is to say not very close at all. Anyway, Poelzig plans to sacrifice Joan in a Satanic ritual during the dark of the moon. He is seen reading a book called The Rites Of Lucifer, while a beautiful blonde woman sleeps next to him. The blonde is Werdegast’s daughter Karen (Lucille Lund), and one of the women in the glass cases is Werdegast’s wife, also named Karen (Lucille Lund). Werdegast bides his time, waiting for the right moment to strike down the mad architect who used to be his friend. A fierce wind hurls menacing clouds across the night sky and the mountains are overcast, as strange guests in evening dress begin to arrive at the house, the men in black, the women in white. They gather in the main hall before a plain but expressionistic altar and Poelzig, dressed in a black robe with a large collar, is their priest, intoning in Latin the words of the Black Mass.

Earlier in the movie, Werdegast kills Poelzig’s black cat but Poelzig, who keeps dead women on display in glass cases, carries a black cat around the house with him while he oversees the women’s apparently sleeping forms. This is about as close as we get to the original Poe story, which is to say not very close at all. Anyway, Poelzig plans to sacrifice Joan in a Satanic ritual during the dark of the moon. He is seen reading a book called The Rites Of Lucifer, while a beautiful blonde woman sleeps next to him. The blonde is Werdegast’s daughter Karen (Lucille Lund), and one of the women in the glass cases is Werdegast’s wife, also named Karen (Lucille Lund). Werdegast bides his time, waiting for the right moment to strike down the mad architect who used to be his friend. A fierce wind hurls menacing clouds across the night sky and the mountains are overcast, as strange guests in evening dress begin to arrive at the house, the men in black, the women in white. They gather in the main hall before a plain but expressionistic altar and Poelzig, dressed in a black robe with a large collar, is their priest, intoning in Latin the words of the Black Mass.

Joan is carried screaming up to the high altar and promptly faints. As the congregation looks on intently, Poelzig offers her body and soul to Satan. The service builds to a crescendo, and one of the women worshipers faints from excitement. Seizing the diversion, Werdegast and his manservant Thamal, who had both been hiding behind the altar, grab Joan and make their way down twisting metal stairs to subterranean tunnels. There Thamal kills one of Poelzig’s servants but is himself mortally wounded. There too, Joan manages to tell Werdegast that his daughter Karen is still alive – and married to his arch-enemy! The news of his daughter drives Werdegast berserk and then, with an agonising cry, he finds Karen’s dead body in the underground laboratory.

Joan is carried screaming up to the high altar and promptly faints. As the congregation looks on intently, Poelzig offers her body and soul to Satan. The service builds to a crescendo, and one of the women worshipers faints from excitement. Seizing the diversion, Werdegast and his manservant Thamal, who had both been hiding behind the altar, grab Joan and make their way down twisting metal stairs to subterranean tunnels. There Thamal kills one of Poelzig’s servants but is himself mortally wounded. There too, Joan manages to tell Werdegast that his daughter Karen is still alive – and married to his arch-enemy! The news of his daughter drives Werdegast berserk and then, with an agonising cry, he finds Karen’s dead body in the underground laboratory.

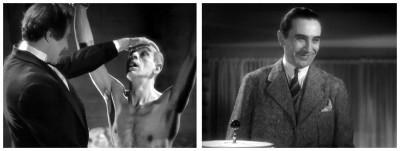

Poelzig rushes down the metal stairs, and Werdegast hurls himself upon him with the strength of a madman. The dying Thamal helps Werdegast to suspend his enemy from a rack and strip him of his robes. “Do you know what I am going to do with you now? Did you ever see an animal skinned? That is what I am going to do. Tear the skin from your body, slowly, bit by bit.” From a surgical table in the lab, Werdegast snatches a scalpel and, laughing maniacally, begins his grisly revenge, as Joan screams. Peter, who has somehow escaped from the cell in which they had placed him and armed himself with a revolver, dashes through the tunnel and fires upon Werdegast. Sinking to the floor, Werdegast manages to say, “You poor fool, I was only trying to help. Now go, please go!” As Peter and Joan flee, Werdegast crawls to a set of large switches set in the wall. Grabbing one, he turns to the torn body of Poelzig. “Five minutes and this switch ignites the dynamite. Five minutes and Marmaros, you and I, this whole rotten cult will be no more!” Peter and Joan dash out of the fortress and down to the road below. Behind them, the house erupts a second after Werdegast’s final words: “It has been a good game, Hjalmar…”

Poelzig rushes down the metal stairs, and Werdegast hurls himself upon him with the strength of a madman. The dying Thamal helps Werdegast to suspend his enemy from a rack and strip him of his robes. “Do you know what I am going to do with you now? Did you ever see an animal skinned? That is what I am going to do. Tear the skin from your body, slowly, bit by bit.” From a surgical table in the lab, Werdegast snatches a scalpel and, laughing maniacally, begins his grisly revenge, as Joan screams. Peter, who has somehow escaped from the cell in which they had placed him and armed himself with a revolver, dashes through the tunnel and fires upon Werdegast. Sinking to the floor, Werdegast manages to say, “You poor fool, I was only trying to help. Now go, please go!” As Peter and Joan flee, Werdegast crawls to a set of large switches set in the wall. Grabbing one, he turns to the torn body of Poelzig. “Five minutes and this switch ignites the dynamite. Five minutes and Marmaros, you and I, this whole rotten cult will be no more!” Peter and Joan dash out of the fortress and down to the road below. Behind them, the house erupts a second after Werdegast’s final words: “It has been a good game, Hjalmar…”

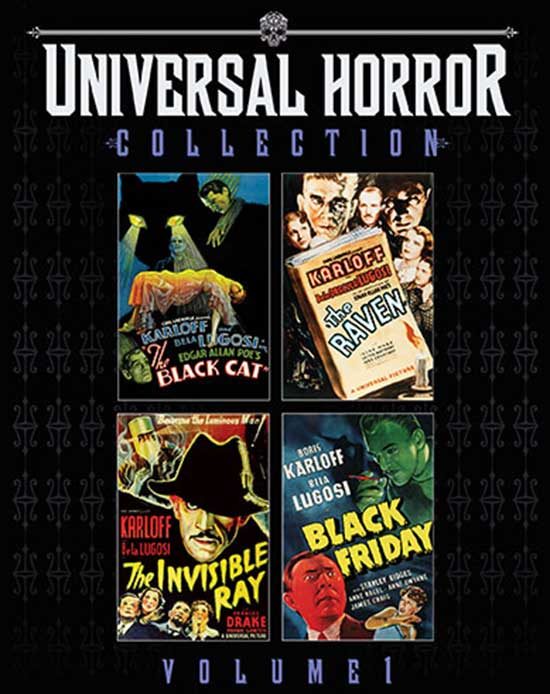

The Black Cat doesn’t make sense in a number of departments. For what bizarre reason does engineer Poelzig have several women suspended in his subterranean display cases? Has Werdegast’s morbid fear of cats been introduced into the plot for no other purpose than a casual link to Poe? We can only guess at the steps that led Poelzig from being both a leader and later a traitor on the field of battle to being the high priest of a Satanic cult. Ulmer complained bitterly that Universal cut the film drastically, which explains some of its incoherence and the script’s weakness. Despite these problems, The Black Cat was extremely popular, Universal’s biggest hit of the year, so much so the studio was moved the following year to cast Bela and Boris together again in The Raven (1935). In The Raven, Lugosi had more of a chance to be centre stage, portraying a plastic surgeon so obsessed with the works of Edgar Allan Poe that he builds several of Poe’s more intriguing torture devices. Karloff plays a gangster whose face Lugosi hideously scars – later to be referenced by several films, from Arsenic And Old Lace (1944) to Batman (1989).

The Black Cat doesn’t make sense in a number of departments. For what bizarre reason does engineer Poelzig have several women suspended in his subterranean display cases? Has Werdegast’s morbid fear of cats been introduced into the plot for no other purpose than a casual link to Poe? We can only guess at the steps that led Poelzig from being both a leader and later a traitor on the field of battle to being the high priest of a Satanic cult. Ulmer complained bitterly that Universal cut the film drastically, which explains some of its incoherence and the script’s weakness. Despite these problems, The Black Cat was extremely popular, Universal’s biggest hit of the year, so much so the studio was moved the following year to cast Bela and Boris together again in The Raven (1935). In The Raven, Lugosi had more of a chance to be centre stage, portraying a plastic surgeon so obsessed with the works of Edgar Allan Poe that he builds several of Poe’s more intriguing torture devices. Karloff plays a gangster whose face Lugosi hideously scars – later to be referenced by several films, from Arsenic And Old Lace (1944) to Batman (1989).

The Raven fails to reach the bar established by The Black Cat, probably because Edgar G. Ulmer did not direct it. Ulmer did very little for Universal and, by the forties, was directing for small independent studios. For the next three decades he directed such melodramas as Bluebeard (1944) and The Man From Planet X (1951) and an interesting remake of Queen Of Atlantis (1932) entitled Journey Beneath The Desert (1961). With its weird and terrifying clashes between good and evil, The Black Cat is one of the most genuinely horrific films of the thirties. It is a clear adaptation of the Germanic stylised horror of the previous decade, probably the closest Hollywood ever got to it. There are no monsters in the film of the kind that Universal had previously so successfully exploited. Even the black cat of the title makes only a minimal and incidental appearance, so far removed from the core of the plot that no-one even bothers to give it a name.

The Raven fails to reach the bar established by The Black Cat, probably because Edgar G. Ulmer did not direct it. Ulmer did very little for Universal and, by the forties, was directing for small independent studios. For the next three decades he directed such melodramas as Bluebeard (1944) and The Man From Planet X (1951) and an interesting remake of Queen Of Atlantis (1932) entitled Journey Beneath The Desert (1961). With its weird and terrifying clashes between good and evil, The Black Cat is one of the most genuinely horrific films of the thirties. It is a clear adaptation of the Germanic stylised horror of the previous decade, probably the closest Hollywood ever got to it. There are no monsters in the film of the kind that Universal had previously so successfully exploited. Even the black cat of the title makes only a minimal and incidental appearance, so far removed from the core of the plot that no-one even bothers to give it a name.

Neither Karloff nor Lugosi is in any way a supernatural creature, yet the obsessions that drive them – revenge, Satanism – bring them into a conflict upon a landscape so evil it makes one shudder. It is not the devil worship itself that is terrifying (although this was new ground for filmmakers and the congregation is cautiously presented as impeccably mannered), it is the fear and dread that hang as oppressive as a storm cloud, over the battlements of Marmaros, the futuristic fortress built over a massive grave site. Few films have ever managed to generate such dread, and in such a stylish shadowy way. That The Black Cat succeeds so singularly well makes it a memorable addition to genre cinema. It’s on this rather upbeat note I’ll simply request your presence next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of Hollywoodland, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Neither Karloff nor Lugosi is in any way a supernatural creature, yet the obsessions that drive them – revenge, Satanism – bring them into a conflict upon a landscape so evil it makes one shudder. It is not the devil worship itself that is terrifying (although this was new ground for filmmakers and the congregation is cautiously presented as impeccably mannered), it is the fear and dread that hang as oppressive as a storm cloud, over the battlements of Marmaros, the futuristic fortress built over a massive grave site. Few films have ever managed to generate such dread, and in such a stylish shadowy way. That The Black Cat succeeds so singularly well makes it a memorable addition to genre cinema. It’s on this rather upbeat note I’ll simply request your presence next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of Hollywoodland, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews