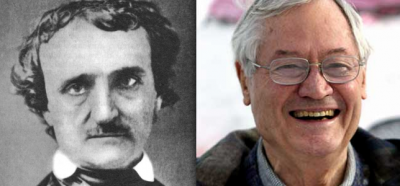

When the cinema of horror was temporarily abandoned in the late fifties, it was mostly low-budget black-and-white films about monsters. At the beginning of the sixties the budgets were lower than ever, but everything else was changing. As monsters flew out the window, doomed neurotics were plodding hauntedly through the door. The day of the Gothic Costume Drama had arrived, and its prophet was a brisk young fellow named Roger Corman. The Gothic was a familiar element in fantastic cinema from the beginning but oddly enough, no matter how medieval the plots, most such Gothics had been set in more-or-less contemporary times. Then Roger, with his writers Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont, discovered Edgar Allan Poe. Both Richard and Charles were responsible for the best of the original Twilight Zone stories with many books still in publication.

When the cinema of horror was temporarily abandoned in the late fifties, it was mostly low-budget black-and-white films about monsters. At the beginning of the sixties the budgets were lower than ever, but everything else was changing. As monsters flew out the window, doomed neurotics were plodding hauntedly through the door. The day of the Gothic Costume Drama had arrived, and its prophet was a brisk young fellow named Roger Corman. The Gothic was a familiar element in fantastic cinema from the beginning but oddly enough, no matter how medieval the plots, most such Gothics had been set in more-or-less contemporary times. Then Roger, with his writers Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont, discovered Edgar Allan Poe. Both Richard and Charles were responsible for the best of the original Twilight Zone stories with many books still in publication.

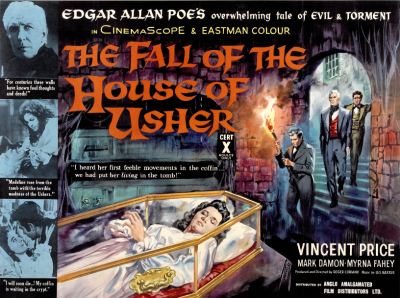

The first, if not the best, of Roger’s Poe adaptations was House Of Usher (1960). Like the subsequent adaptations, it was designed by Daniel Haller (who later became a fair director himself) and photographed by Floyd Crosby in Pathecolor, a process which emphasised the blue-green end of the spectrum while underplaying the red-yellow end, thus giving the film a ghastly patina, echoing the morbid lifestyle of the rambling old mansion’s decadent occupants. Most of Roger’s Poe films have a subtext in which a place – usually an ancient house, cob-webbed and decaying – comes to stand for all the traps of old memories, sins, regrets. The camera that wanders down the gloomy corridors is effectively tracking through Vincent Price‘s un-aired mind. In his Poe films, Roger abandoned his usual speedy cutting and vigour for a hypnotic, rather ponderous style which seems to float lethargically through nightmares that are not so much terrifying as excruciatingly claustrophobic. Yet audiences loved them, and a number of follow-ups were produced, including The Pit And The Pendulum (1961), The Premature Burial (1962), Tales Of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), The Terror (1963) and The Tomb Of Ligeia (1964). Of these, The Tomb Of Ligeia was the most accomplished, along with The Haunted Palace (1963) and The Masque Of The Red Death (1964).

The first, if not the best, of Roger’s Poe adaptations was House Of Usher (1960). Like the subsequent adaptations, it was designed by Daniel Haller (who later became a fair director himself) and photographed by Floyd Crosby in Pathecolor, a process which emphasised the blue-green end of the spectrum while underplaying the red-yellow end, thus giving the film a ghastly patina, echoing the morbid lifestyle of the rambling old mansion’s decadent occupants. Most of Roger’s Poe films have a subtext in which a place – usually an ancient house, cob-webbed and decaying – comes to stand for all the traps of old memories, sins, regrets. The camera that wanders down the gloomy corridors is effectively tracking through Vincent Price‘s un-aired mind. In his Poe films, Roger abandoned his usual speedy cutting and vigour for a hypnotic, rather ponderous style which seems to float lethargically through nightmares that are not so much terrifying as excruciatingly claustrophobic. Yet audiences loved them, and a number of follow-ups were produced, including The Pit And The Pendulum (1961), The Premature Burial (1962), Tales Of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), The Terror (1963) and The Tomb Of Ligeia (1964). Of these, The Tomb Of Ligeia was the most accomplished, along with The Haunted Palace (1963) and The Masque Of The Red Death (1964).

The only element of Poe in The Haunted Palace is the title. The story is taken from the lurid pulp classic The Case Of Charles Dexter Ward by H.P. Lovecraft. By this time Roger had perfected his technique of the gliding, inexorable camera prying more and more deeply into the mysteries of dark places. A curse lies over the village of Arkham, now populated by deformed mutant beings as a result of witchcraft many years before. In the cellar of the Curwen mansion, down deep in a stone pit, lives a demonic creature, one of Lovecraft’s elder gods – or perhaps an alien being from another world – whose malign influence infects those who live there. Vincent Price, who inherits the house, is gradually possessed by the spirit of his ancestor, the burned witch. Once again the subtext tells of the past reclaiming the present. It also reveals a new psychological element, a Freudian repressed ‘thing’ that we eventually confront. All this is pretty rich stuff, and despite the garish conventions of pulp horror that Roger never seems to have struggled against too hard (including some ludicrously hammy overacting), his powerful pictorial sense makes this (and his other Poe movies) an authentically cinematic experience.

The only element of Poe in The Haunted Palace is the title. The story is taken from the lurid pulp classic The Case Of Charles Dexter Ward by H.P. Lovecraft. By this time Roger had perfected his technique of the gliding, inexorable camera prying more and more deeply into the mysteries of dark places. A curse lies over the village of Arkham, now populated by deformed mutant beings as a result of witchcraft many years before. In the cellar of the Curwen mansion, down deep in a stone pit, lives a demonic creature, one of Lovecraft’s elder gods – or perhaps an alien being from another world – whose malign influence infects those who live there. Vincent Price, who inherits the house, is gradually possessed by the spirit of his ancestor, the burned witch. Once again the subtext tells of the past reclaiming the present. It also reveals a new psychological element, a Freudian repressed ‘thing’ that we eventually confront. All this is pretty rich stuff, and despite the garish conventions of pulp horror that Roger never seems to have struggled against too hard (including some ludicrously hammy overacting), his powerful pictorial sense makes this (and his other Poe movies) an authentically cinematic experience.

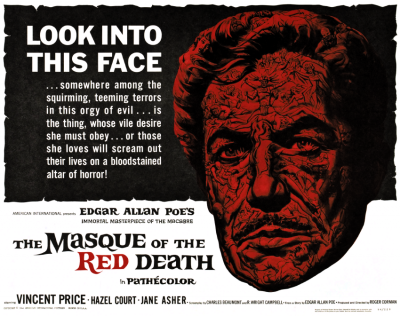

The Masque Of The Red Death is considered by many to be Roger’s most effective work in this area, and it is certainly his most stately and eloquent. It is, however, all so remote and stagy that it is difficult to take too seriously the plight of a palace full of decadents dancing the night away, while malignant tortured dwarfs hop about and Death stalks the red-lit room in the guise of Plague (also in the guise of Vincent Price). Curiously, a masque, in the old Elizabethan sense of the word, is exactly what it is: More of a venomous ballet than an actual story. The evocative use of colour is stylised to an extraordinary degree. In this as in most Roger Corman movies, women are glamorous, often corrupt icons. His image of femaleness is disquietingly sexual, cool and voluptuous. There are no erotic delights in the world of Roger’s nightmares, and precious little warmth of any kind.

Roger had not entirely abandoned science fiction while all this was going on. One of his best and most modest films was X: The Man With The X-Ray Eyes (1963) starring Ray Milland as Doctor Xavier, who invents a serum that allows him to see within his patients. It works all too well, and his sight into the horrors that go on inside perfectly ordinary-seeming people drives him close to madness. Nor does it end there. Soon his vision is penetrating to the heart of the cosmos – the deepest mysteries of things. All this is cheaply symbolised visually by using black contact lenses, which have the paradoxical effects of making him appear sightless. Getting a job as a mind-reader in a tatty carnival does not help and eventually, echoing Oedipus Rex many centuries earlier, he takes decisive action after hearing an evangelist preaching “If thine eye offends thee, pluck it out!” It’s all done in the best possible taste.

Roger had not entirely abandoned science fiction while all this was going on. One of his best and most modest films was X: The Man With The X-Ray Eyes (1963) starring Ray Milland as Doctor Xavier, who invents a serum that allows him to see within his patients. It works all too well, and his sight into the horrors that go on inside perfectly ordinary-seeming people drives him close to madness. Nor does it end there. Soon his vision is penetrating to the heart of the cosmos – the deepest mysteries of things. All this is cheaply symbolised visually by using black contact lenses, which have the paradoxical effects of making him appear sightless. Getting a job as a mind-reader in a tatty carnival does not help and eventually, echoing Oedipus Rex many centuries earlier, he takes decisive action after hearing an evangelist preaching “If thine eye offends thee, pluck it out!” It’s all done in the best possible taste.

Roger’s own genius is not unlike Doctor Xavier’s in the film. He can see right through the fat of conventional horror cliches to the lethal metaphor that lies hidden beneath. He makes good horror films because they all have something to say, beyond the immediate nightmares they so melodramatically describe. So please join me next week with your morbid curiosity well-prepared for another step beyond the inner limits of the outer sanctum with a touch of evil from the amazing zone known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Roger’s own genius is not unlike Doctor Xavier’s in the film. He can see right through the fat of conventional horror cliches to the lethal metaphor that lies hidden beneath. He makes good horror films because they all have something to say, beyond the immediate nightmares they so melodramatically describe. So please join me next week with your morbid curiosity well-prepared for another step beyond the inner limits of the outer sanctum with a touch of evil from the amazing zone known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Nigel,

I love Corman’s Poe adaptations! Nice article. I just finished watching a great doc detailing the history of the American horror film called “Nightmares in Red, White and Blue” that touches briefly on these films. There’s also “Shlock”, which is another fun doc about early exploitation filmmaking that is worth checking out.

I can’t thank you enough for reading! Of course, there’s enough material on Roger Corman and AIP to fill several volumes. Two of my favourite books on the subject are How I Made A Hundred Movies And Never Lost A Dime by Roger Corman, and Fast And Furious The Story Of American International Pictures by Mark Thomas McGee – very thorough indeed! Toodles!