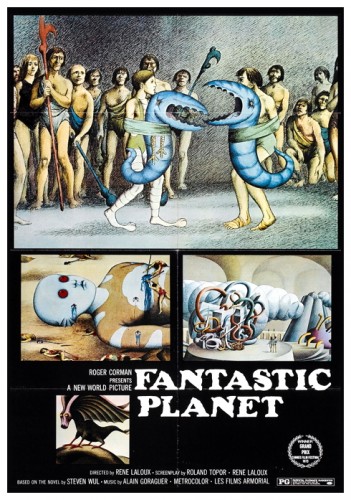

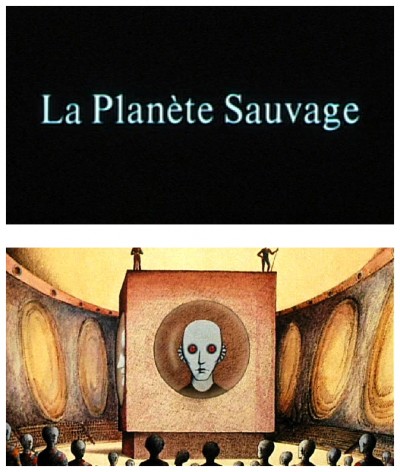

“La Planète Sauvage, also known as Fantastic Planet, is a surrealist story based on the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia. Set on a far distant world, human beings or ‘Oms’ have been domesticated by the gigantic Draags. Wild Oms however are a problem and are exterminated by the dozen. One domesticated om named Terr is able to escape his masters with a headset that puts information directly into the brain. Armed now with the Draags technology he leads the Oms in an attempt to make life better for them – but will the deomizing destroy them?” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

René Laloux was born in Paris in 1929 and went to art school to study painting. After some time working in advertising, he got a job in the La Borde psychiatric institution where he began experimenting in animation with the interns. It is at the psychiatric institution that he made Monkey’s Teeth (Les Dents Du Singe 1960) in collaboration with Paul Grimault‘s studio, from a script written by the interns at La Borde. He started directing professionally, making another short with Roland Topor entitled Dead Time (Les Temps Morts 1964), followed by his most famous short film The Snails (Les Escargots 1965). It was quite natural for Laloux to turn to paper cutouts for these three films, a choice dictated as much by taste as by necessity. Dead Time is an anti-militarist film peppered with Topor’s black humour, and its crosshatched graphic style, which looks rather like etching, became Laloux’s trademark signature.

The Snails presents us with an everyday fantasy world in which a gardener growing vegetables unwittingly sets off a series of catastrophes. The film won numerous international prizes, including the Grand Prix at the Mamaïa Festival in Romania and the Special Jury Prize at the Cracow Festival. Whereas Laloux was still an unknown, Topor had already made something of a name for himself as an engraver, illustrator and screenwriter, as well as publishing novels and short stories. By the late sixties his artistic work had achieved an international reputation and his work was exhibited in London, New York and Chicago, while Laloux himself continued to paint but without much success in that particular field. Together they embarked on their first feature-length animated feature, the surreal science fiction film Fantastic Planet (La Planète Sauvage 1973).

The Snails presents us with an everyday fantasy world in which a gardener growing vegetables unwittingly sets off a series of catastrophes. The film won numerous international prizes, including the Grand Prix at the Mamaïa Festival in Romania and the Special Jury Prize at the Cracow Festival. Whereas Laloux was still an unknown, Topor had already made something of a name for himself as an engraver, illustrator and screenwriter, as well as publishing novels and short stories. By the late sixties his artistic work had achieved an international reputation and his work was exhibited in London, New York and Chicago, while Laloux himself continued to paint but without much success in that particular field. Together they embarked on their first feature-length animated feature, the surreal science fiction film Fantastic Planet (La Planète Sauvage 1973).

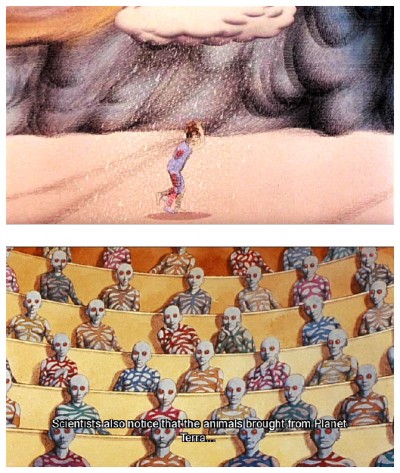

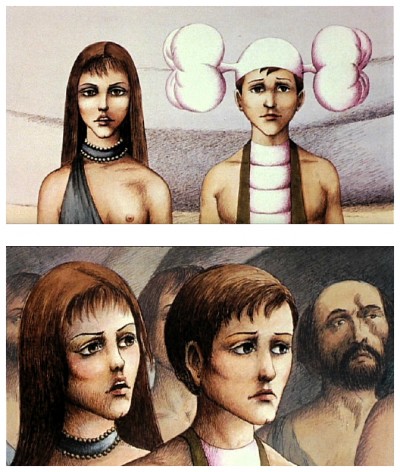

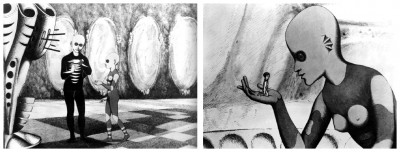

Fantastic Planet takes place on a strange alien planet called Ygam dominated by the Draags, giant blue-skinned humanoids who seem to spend most of their time meditating. Tiva, the daughter of the Draag Prime Minister, finds a wild baby Om (hommes, in French, means human), who she raises as a pet and names him Terr (Terre, in French, means Earth). The tiny Oms, miniscule in comparison with the Draags, are either domesticated rodent-like pets, or feral and wild. Draag children seem to spend their days playing with their pets, dressing them up or having them fight each other, often to the death. Terr grows up quickly and, as Tiva likes to hold him while she receives her lessons through a set of earphones, Terr also becomes familiar with the totality of the Draag education. Now educated on par with any Draag, Terr escapes his pet captivity, steals the earphones, and searches out the feral Oms in the hope of organising them and bestowing them, like Prometheus, with the fire of Draag knowledge.

Fantastic Planet takes place on a strange alien planet called Ygam dominated by the Draags, giant blue-skinned humanoids who seem to spend most of their time meditating. Tiva, the daughter of the Draag Prime Minister, finds a wild baby Om (hommes, in French, means human), who she raises as a pet and names him Terr (Terre, in French, means Earth). The tiny Oms, miniscule in comparison with the Draags, are either domesticated rodent-like pets, or feral and wild. Draag children seem to spend their days playing with their pets, dressing them up or having them fight each other, often to the death. Terr grows up quickly and, as Tiva likes to hold him while she receives her lessons through a set of earphones, Terr also becomes familiar with the totality of the Draag education. Now educated on par with any Draag, Terr escapes his pet captivity, steals the earphones, and searches out the feral Oms in the hope of organising them and bestowing them, like Prometheus, with the fire of Draag knowledge.

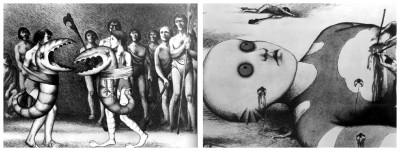

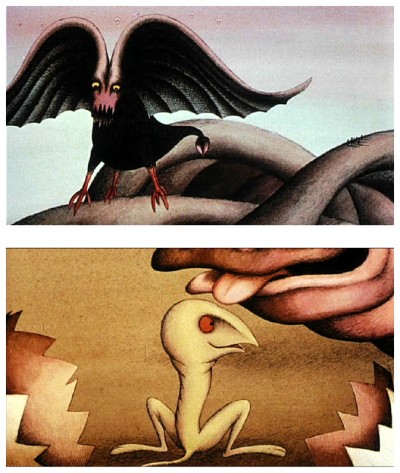

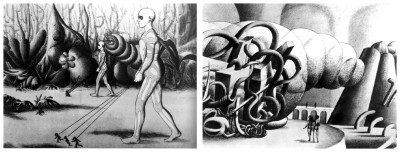

The animated landscape Laloux creates for the Draag world is surreal, bizarre, beautiful and profoundly disturbing. As Terr makes his way to the feral Oms, he encounters a variety of strange living organisms, seemingly drawn from drug-induced nightmares. The nightmare landscape strongly echoes the animation George Dunning created for Yellow Submarine (1968) in that world of Pepperland and the Blue Meanies. The opening sequence of the infant Terr watching his mother’s death and seeing her body poked by curious Draag children (as any child would a dead animal they came across) is rather disturbing. Because the Draags are the stuff of animated nightmares, we cannot identify with them, at least not in the same way we identify with the pathetic Oms and the strong verisimilitude in which they are rendered.

The animated landscape Laloux creates for the Draag world is surreal, bizarre, beautiful and profoundly disturbing. As Terr makes his way to the feral Oms, he encounters a variety of strange living organisms, seemingly drawn from drug-induced nightmares. The nightmare landscape strongly echoes the animation George Dunning created for Yellow Submarine (1968) in that world of Pepperland and the Blue Meanies. The opening sequence of the infant Terr watching his mother’s death and seeing her body poked by curious Draag children (as any child would a dead animal they came across) is rather disturbing. Because the Draags are the stuff of animated nightmares, we cannot identify with them, at least not in the same way we identify with the pathetic Oms and the strong verisimilitude in which they are rendered.

Not unlike Moses, Terr attempts to organise a mass exodus of Oms to find some kind of promised land where they can live in peace and safety, the Draags begin a program of mass extermination of all the Oms in the park they had been calling home. Evoking strong images of the Holocaust, particularly with the poison-gas mass exterminations and the collaborating Oms, wearing gas masks, running through the park on leashes searching for escaped Oms, this film really underlines that, despite being an ‘animated’ feature, not all animation is appropriate for children, especially such a profound and deeply upsetting animated classic as Fantastic Planet. Laloux and Topor adapted their story from the novel Oms En Série by Stefan Wul and, as it has a political themes, it is rather fitting that it was filmed in Jiri Trinka‘s animation studio in Prague.

Not unlike Moses, Terr attempts to organise a mass exodus of Oms to find some kind of promised land where they can live in peace and safety, the Draags begin a program of mass extermination of all the Oms in the park they had been calling home. Evoking strong images of the Holocaust, particularly with the poison-gas mass exterminations and the collaborating Oms, wearing gas masks, running through the park on leashes searching for escaped Oms, this film really underlines that, despite being an ‘animated’ feature, not all animation is appropriate for children, especially such a profound and deeply upsetting animated classic as Fantastic Planet. Laloux and Topor adapted their story from the novel Oms En Série by Stefan Wul and, as it has a political themes, it is rather fitting that it was filmed in Jiri Trinka‘s animation studio in Prague.

The story may seem slight to some viewers but it is undeniably interesting, and it makes the key point that education is vital to revolution. The sudden, rather vague ending fails to completely satisfy, the animation is often static and, when coupled with the monotone voices heard in the English-language version (distributed by my old friend Roger Corman), tends to give the film a sluggish pace during those times when the excitement should be building. The fluid French voices of Jennifer Drake, Eric Baugin, Jean Topart and Jean Valmont are replaced by Americans Cynthia Adler, Barry Bostwick, Mark Gruner and Nora Helm. Best of all are the weird alien creatures that inhabit this savage planet, but there are too few of them. Fantastic Planet is definitely worth seeing, but a little disappointing in that with only a few minor changes this could have been a real masterpiece. However, the fact that it was an animated motion picture with a lyrical strain made it sufficiently different and its originality lay in the fact that instead of describing brute coercion it creates an ambiance of gentle slavery, a highly premonitory satire.

The story may seem slight to some viewers but it is undeniably interesting, and it makes the key point that education is vital to revolution. The sudden, rather vague ending fails to completely satisfy, the animation is often static and, when coupled with the monotone voices heard in the English-language version (distributed by my old friend Roger Corman), tends to give the film a sluggish pace during those times when the excitement should be building. The fluid French voices of Jennifer Drake, Eric Baugin, Jean Topart and Jean Valmont are replaced by Americans Cynthia Adler, Barry Bostwick, Mark Gruner and Nora Helm. Best of all are the weird alien creatures that inhabit this savage planet, but there are too few of them. Fantastic Planet is definitely worth seeing, but a little disappointing in that with only a few minor changes this could have been a real masterpiece. However, the fact that it was an animated motion picture with a lyrical strain made it sufficiently different and its originality lay in the fact that instead of describing brute coercion it creates an ambiance of gentle slavery, a highly premonitory satire.

After the financial success of Fantastic Planet, René Laloux went on to work with Heavy Metal magazine artist Jean Giraud aka Mœbius to create a lesser known film entitled Time Masters (Les Maîtres Du Temps 1981) based on another of Stefan Wul‘s science fiction novels, L’Orphelin De Perdide, and Light Years (Gandahar 1988) from a screenplay adapted by the great Isaac Asimov. Unfortunately, the American version of Light Years was not as successful as the French version and grossed less than US$400,000 on its initial release, but that’s another story for another time. Now, having demonstrated to you the perils of probing the dark depths of French cinema, I’ll vanish into the night, after first inviting you to rendezvous with me at the same time next week when I’ll discuss another dubious treasure for…Horror News! Toodles!

After the financial success of Fantastic Planet, René Laloux went on to work with Heavy Metal magazine artist Jean Giraud aka Mœbius to create a lesser known film entitled Time Masters (Les Maîtres Du Temps 1981) based on another of Stefan Wul‘s science fiction novels, L’Orphelin De Perdide, and Light Years (Gandahar 1988) from a screenplay adapted by the great Isaac Asimov. Unfortunately, the American version of Light Years was not as successful as the French version and grossed less than US$400,000 on its initial release, but that’s another story for another time. Now, having demonstrated to you the perils of probing the dark depths of French cinema, I’ll vanish into the night, after first inviting you to rendezvous with me at the same time next week when I’ll discuss another dubious treasure for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews