SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Captain Nemo has built a fantastic submarine for his mission of revenge. He has traveled over 20,000 leagues in search of Charles Denver, the man who caused the death of Princess Daaker. Seeing what he had done, Denver took the daughter to his yacht and sailed away. He abandoned her and a sailor on a mysterious island and has come back after all these years to see if she is still alive and if the nightmares he has will stop. The daughter has been found by five survivors of a Union Army balloon that crashed near the island. At sea, Professor Aronnax was aboard the ship ‘Abraham Lincoln’ when Nemo rammed it and threw the Professor, his daughter and two others into the water. Prisoners at first, they are now treated as guests to view the underwater world and to hunt under the waves. Nemo will also tells them about the Nautilus and the revenge that has driven him for all these years.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

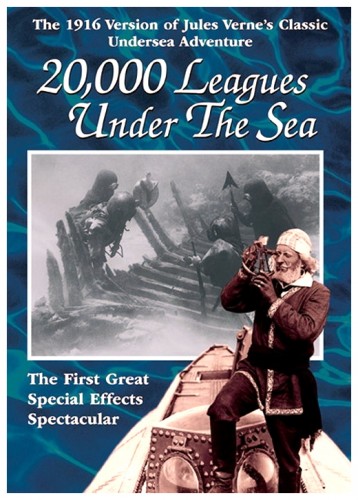

Brothers August Lumière and Louis Lumière gave the first public demonstration of their ‘cinematography machine’ in Paris in 1895. Seven years later Georges Méliès made his film A Trip To The Moon (1902), which is probably the first film actually based – however loosely – on the work of a science fiction author, though elements of science fiction can be detected in the trick photography of the earliest films. Five years later he applied the same treatment to Jules Verne‘s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1907) although it’s doubtful whether the illustrious author would have approved of the half-naked sea nymphs. In England science fiction was treated more seriously in Charles Urban‘s The Airship Destroyer (1909), which proved popular and prompted two sequels: The Aerial Anarchists (1911) and The Pirates Of 1920 (1911). Meanwhile in America the Edison company had made the first version of Frankenstein (1910) but, after this first flurry, science fiction cinema fell quiet for the next few years until the ‘big ticket’ of 1916 arrived, none other than a serious attempt to remake 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1916).

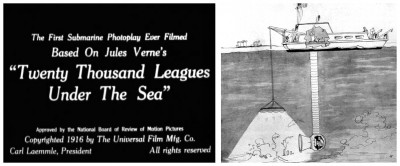

Directed by Stuart Paton, it was produced by Carl Laemmle‘s Universal company, the studio that was to become best known for its series of horror films in the thirties such as Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1931), The Invisible Man (1933) and so on. But the most interesting aspect of the 1916 version of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea was the involvement in its making of a man named Ernest Williamson who, with his brother George Williamson, had developed the first efficient technique for filming underwater. They built an underwater chamber they called the ‘photosphere’ which was indeed spherical and made of thick steel, containing one large porthole. The photosphere was attached to a barge floating overhead by a long tube made of removable metal sections which were wide enough to permit a man to climb through them. Air was pumped down the tube into the sphere from the barge above, and the whole structure was strong enough to be lowered to a depth of about twenty-five metres.

Directed by Stuart Paton, it was produced by Carl Laemmle‘s Universal company, the studio that was to become best known for its series of horror films in the thirties such as Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1931), The Invisible Man (1933) and so on. But the most interesting aspect of the 1916 version of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea was the involvement in its making of a man named Ernest Williamson who, with his brother George Williamson, had developed the first efficient technique for filming underwater. They built an underwater chamber they called the ‘photosphere’ which was indeed spherical and made of thick steel, containing one large porthole. The photosphere was attached to a barge floating overhead by a long tube made of removable metal sections which were wide enough to permit a man to climb through them. Air was pumped down the tube into the sphere from the barge above, and the whole structure was strong enough to be lowered to a depth of about twenty-five metres.

The Williamsons first tested it in the clear waters off Nassau in the Bahamas and made a short film which included shots of local boys diving for coins and a man attacking a shark with a knife. Their underwater films soon attracted attention and, when Universal decided to film Verne’s novel, the Williamsons were hired to handle the sea footage. Director Paton concocted some absurd additions to the Verne story including the discovery of a scantily-clad girl on an isolated island, but Ernest Williamson was determined to remain as faithful as possible to the original tale as far as his part in the production was concerned: “To vindicate Verne the dreamer was my problem, to make Jules Verne’s dream come through, but where were the unique and extraordinary props? No doubt there were plenty of obsolete submarines knocking about that would serve as the Nautilus, but my confidence was soon punctured. I found it impossible to get a hold of a submarine.”

The Williamsons first tested it in the clear waters off Nassau in the Bahamas and made a short film which included shots of local boys diving for coins and a man attacking a shark with a knife. Their underwater films soon attracted attention and, when Universal decided to film Verne’s novel, the Williamsons were hired to handle the sea footage. Director Paton concocted some absurd additions to the Verne story including the discovery of a scantily-clad girl on an isolated island, but Ernest Williamson was determined to remain as faithful as possible to the original tale as far as his part in the production was concerned: “To vindicate Verne the dreamer was my problem, to make Jules Verne’s dream come through, but where were the unique and extraordinary props? No doubt there were plenty of obsolete submarines knocking about that would serve as the Nautilus, but my confidence was soon punctured. I found it impossible to get a hold of a submarine.”

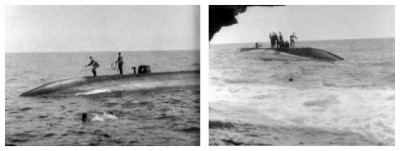

But this didn’t stop Williamson for long – he had his own metal submarine specially built. He claims it was a hundred feet long and could be operated by one man but on the first trial run, watched by the Governor of the Bahamas, things went wrong. “I knew it could be submerged but I was not so confident that it could be raised to the surface with entire success at the first attempt. Ordinarily I planned to handle the Nautilus myself but on this occasion I trusted her to an assistant who was clad in a diving suit as a precaution. All was going well – up rose the railed platform, up came the rounded cigar-shaped hull, and then! Cries of dismay from the spectators. Wildly the craft rolled. It heeled from side to side in imminent danger of turning turtle and drowning the man within. And then slowly, smoothly, the Nautilus rolled back and came to rest at an even keel. I saw the Governor slap the Chief of Police on the back and heard him exclaim, ‘By jove, these motion picture fellows, you can’t baffle them, you know’.”

But this didn’t stop Williamson for long – he had his own metal submarine specially built. He claims it was a hundred feet long and could be operated by one man but on the first trial run, watched by the Governor of the Bahamas, things went wrong. “I knew it could be submerged but I was not so confident that it could be raised to the surface with entire success at the first attempt. Ordinarily I planned to handle the Nautilus myself but on this occasion I trusted her to an assistant who was clad in a diving suit as a precaution. All was going well – up rose the railed platform, up came the rounded cigar-shaped hull, and then! Cries of dismay from the spectators. Wildly the craft rolled. It heeled from side to side in imminent danger of turning turtle and drowning the man within. And then slowly, smoothly, the Nautilus rolled back and came to rest at an even keel. I saw the Governor slap the Chief of Police on the back and heard him exclaim, ‘By jove, these motion picture fellows, you can’t baffle them, you know’.”

“Accordingly, preparations were made to film the first episode in Jules Verne’s tale, the ramming of the Abraham Lincoln. It was not such smooth sailing as I thought it would be. My Nautilus did not possess the great ‘iron spur’ that Captain Nemo had provided on his submarine. He might ram a frigate with ease, passing through it like a needle through sackcloth, but for me to drive my submarine into the hull of an old brig might result in the destruction of the undersea craft with perhaps no great damage to the tough old-fashioned warship we were supposed to destroy.” One might ask at this point why Williamson didn’t make use of miniatures, as the 1954 Walt Disney version of the film was later to do. This was simply because model work would have been regarded as ‘cheating’ by audiences of the day.

“Accordingly, preparations were made to film the first episode in Jules Verne’s tale, the ramming of the Abraham Lincoln. It was not such smooth sailing as I thought it would be. My Nautilus did not possess the great ‘iron spur’ that Captain Nemo had provided on his submarine. He might ram a frigate with ease, passing through it like a needle through sackcloth, but for me to drive my submarine into the hull of an old brig might result in the destruction of the undersea craft with perhaps no great damage to the tough old-fashioned warship we were supposed to destroy.” One might ask at this point why Williamson didn’t make use of miniatures, as the 1954 Walt Disney version of the film was later to do. This was simply because model work would have been regarded as ‘cheating’ by audiences of the day.

The techniques for filming miniatures relatively realistically weren’t developed until the twenties – before then, model shots were always very obvious and filmmakers avoided such trickery as much as possible. So Williamson was obliged to create the effect of the Nautilus ramming another vessel with full-scale props. Somehow he had to suggest that the frigate had received a sudden violent shock, and one of his assistants came up with the bizarre idea of placing water-filled barrels on the deck and, at a given signal, rolling them in unison from one side of the ship to the other, thus causing her to lurch heavily. A local rum importer was willing to loan the film company the necessary barrels and all through the night fifty men sweated to fill them with seawater and then place them on greased runways. The next day, just as they were preparing to go back to sea, the owner of the barrels appeared and demanded their immediate return so, for Williamson, it was back to the drawing board.

The techniques for filming miniatures relatively realistically weren’t developed until the twenties – before then, model shots were always very obvious and filmmakers avoided such trickery as much as possible. So Williamson was obliged to create the effect of the Nautilus ramming another vessel with full-scale props. Somehow he had to suggest that the frigate had received a sudden violent shock, and one of his assistants came up with the bizarre idea of placing water-filled barrels on the deck and, at a given signal, rolling them in unison from one side of the ship to the other, thus causing her to lurch heavily. A local rum importer was willing to loan the film company the necessary barrels and all through the night fifty men sweated to fill them with seawater and then place them on greased runways. The next day, just as they were preparing to go back to sea, the owner of the barrels appeared and demanded their immediate return so, for Williamson, it was back to the drawing board.

“Again I read and reread my copy of 20,000 Leagues trying to find a way out. At last I had it! In the story the frigate fired a shot at the Nautilus from a distance, the first shot missing the submarine, the second striking it but glancing off. Here was my chance, my way out of the dilemma. I would have the frigate fire at the oncoming Nautilus at close range and, in the cloud of powder smoke and the tense excitement of the scene, no-one would notice whether or not the Abraham Lincoln registered a terrible shock. Jockeying the vessels into position as they surged through the open sea, I ran the Nautilus diagonally under the frigate’s bows. Cameras clicked, the uniformed crew of the warship rushed excited forward and peered with amazed faces over the bulwarks. Then the impersonator of Verne’s great character, Ned Land, raised his weapon and heaved with all his strength, but he had forgotten a most important detail – he had failed to have the line which he was holding coiled, free to run with the harpoon. As the harpoon sped through the air, the rope whipped into a loop, wrapped about the actor’s neck and came within an ace of flinging him from his perch into the sea.”

“Again I read and reread my copy of 20,000 Leagues trying to find a way out. At last I had it! In the story the frigate fired a shot at the Nautilus from a distance, the first shot missing the submarine, the second striking it but glancing off. Here was my chance, my way out of the dilemma. I would have the frigate fire at the oncoming Nautilus at close range and, in the cloud of powder smoke and the tense excitement of the scene, no-one would notice whether or not the Abraham Lincoln registered a terrible shock. Jockeying the vessels into position as they surged through the open sea, I ran the Nautilus diagonally under the frigate’s bows. Cameras clicked, the uniformed crew of the warship rushed excited forward and peered with amazed faces over the bulwarks. Then the impersonator of Verne’s great character, Ned Land, raised his weapon and heaved with all his strength, but he had forgotten a most important detail – he had failed to have the line which he was holding coiled, free to run with the harpoon. As the harpoon sped through the air, the rope whipped into a loop, wrapped about the actor’s neck and came within an ace of flinging him from his perch into the sea.”

There were other problems. First, the cannon exploded prematurely, leaving two of the crew with burns to the face and suffering from temporary blindness, and then the sharks came. “The triangular fins were cutting the water around the frigate. Scraps of food thrown overboard had attracted them. The actors who were to take the parts of Ned Land, Professor Aronnax and Conseil flatly refused to throw themselves overboard as the story demanded, and nor do I blame them. Doubles had to be provided to act their parts in this phase of the scene.” One wonders how the doubles were led to jump into the shark-infested sea. Despite all the problems, Williamson finally achieved what he wanted on film and, together with the footage shot by director Stuart Paton, the movie was released in 1916 in time to coincide with the news that a German U-boat had slipped through the blockades and sunk a dozen British ships outside New York.

There were other problems. First, the cannon exploded prematurely, leaving two of the crew with burns to the face and suffering from temporary blindness, and then the sharks came. “The triangular fins were cutting the water around the frigate. Scraps of food thrown overboard had attracted them. The actors who were to take the parts of Ned Land, Professor Aronnax and Conseil flatly refused to throw themselves overboard as the story demanded, and nor do I blame them. Doubles had to be provided to act their parts in this phase of the scene.” One wonders how the doubles were led to jump into the shark-infested sea. Despite all the problems, Williamson finally achieved what he wanted on film and, together with the footage shot by director Stuart Paton, the movie was released in 1916 in time to coincide with the news that a German U-boat had slipped through the blockades and sunk a dozen British ships outside New York.

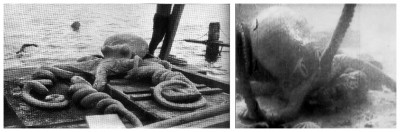

With the sudden new interest in submarines the film was assured of success, but audiences particularly marveled at the underwater sequences which included many shots of the denizens of the deep in their natural habitat for the very first time. Probably the most spectacular of the underwater scenes involved a fight between a couple of divers and a giant octopus. With their customary dislike of admitting to the use of fakery, both the filmmakers and the studio created the impression in their publicity that the octopus was real. It was nearly two decades later that Williamson admitted somewhat shamefacedly that the octopus had not been real after all. Instead it had been constructed out of rubber and operated from within by a hard-hat diver who wore a metal helmet with an air hose leading to the surface. The tentacles contained springs that kept them coiled but, when compressed air was forced into them, the tentacles straightened out and when the air was released they coiled up again. The diver inside the octopus head manipulated a series of levers that fed the air into the tentacles, and the result was relatively effective if a little primitive by today’s standards.

With the sudden new interest in submarines the film was assured of success, but audiences particularly marveled at the underwater sequences which included many shots of the denizens of the deep in their natural habitat for the very first time. Probably the most spectacular of the underwater scenes involved a fight between a couple of divers and a giant octopus. With their customary dislike of admitting to the use of fakery, both the filmmakers and the studio created the impression in their publicity that the octopus was real. It was nearly two decades later that Williamson admitted somewhat shamefacedly that the octopus had not been real after all. Instead it had been constructed out of rubber and operated from within by a hard-hat diver who wore a metal helmet with an air hose leading to the surface. The tentacles contained springs that kept them coiled but, when compressed air was forced into them, the tentacles straightened out and when the air was released they coiled up again. The diver inside the octopus head manipulated a series of levers that fed the air into the tentacles, and the result was relatively effective if a little primitive by today’s standards.

After the huge success of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, Williamson hoped to make a film version of Mysterious Island, but it wasn’t until the mid-twenties that the project got underway. It was an ill-fated movie, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll wrap-up this week’s burnt offering by profusely thanking Ernest Williamson‘s autobiography Twenty Years Under The Sea published in 1935 by Bodley Head for assisting my research for this article, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another cinematic dog from Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

After the huge success of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, Williamson hoped to make a film version of Mysterious Island, but it wasn’t until the mid-twenties that the project got underway. It was an ill-fated movie, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll wrap-up this week’s burnt offering by profusely thanking Ernest Williamson‘s autobiography Twenty Years Under The Sea published in 1935 by Bodley Head for assisting my research for this article, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another cinematic dog from Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews