SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

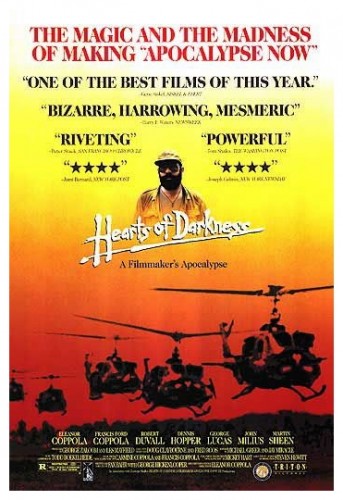

“Documents the sensational events surrounding the making of Apocalypse Now and Francis Ford Coppola’s struggle with nature, governments, actors and self-doubt. Includes footage and sound secretly recorded by Eleanor Coppola, wife of Francis.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

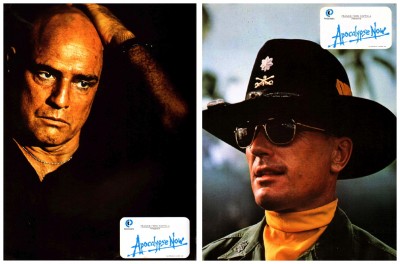

Eleanor Coppola taped and filmed her husband, often without his knowledge, on the set of Apocalypse Now (1979) while everything fell apart around him – Martin Sheen‘s heart attack, a devastating typhoon, the unreliable Philippine army, daily threats by the studio to pull the plug, a rambling Marlon Brando – they’re all here in this extraordinary documentary. Like Burden Of Dreams (1982) concerning the making of Werner Herzog‘s Fitzcarraldo (1982), Hearts Of Darkness (1991) is almost as intense and powerful as the film it chronicles. Francis Ford Coppola first heard about the idea that would become the script for Apocalypse Now from John Milius and George Lucas in the late sixties, when Coppola was working at Warner Brothers as a screenwriter:

“John was telling unbelievable stories about many of his surfer friends who returned from Vietnam and the action there. He wanted to write a screenplay about it and alternately called it The Psychedelic Soldier and Apocalypse Now. Meanwhile Carroll Ballard was planning to put Heart Of Darkness into production and I was writing The Conversation (1974). There was a lot of cross-fertilisation going on.” Later, when Coppola established his production company American Zoetrope, he gave Milius funds to write Apocalypse Now. “I called George Lucas and let him know that I now owned the script and did he want to direct it. George said he was about to undertake a new science fiction project and wouldn’t be able to get to it for well over a year. Subsequently, I called John Milius and asked if he wanted to direct it, and John was also disposed on another project. Then I thought maybe if I directed it myself as a big action war film, American Zoetrope could make a lot of money which we could use to make our small personal films.”

“John was telling unbelievable stories about many of his surfer friends who returned from Vietnam and the action there. He wanted to write a screenplay about it and alternately called it The Psychedelic Soldier and Apocalypse Now. Meanwhile Carroll Ballard was planning to put Heart Of Darkness into production and I was writing The Conversation (1974). There was a lot of cross-fertilisation going on.” Later, when Coppola established his production company American Zoetrope, he gave Milius funds to write Apocalypse Now. “I called George Lucas and let him know that I now owned the script and did he want to direct it. George said he was about to undertake a new science fiction project and wouldn’t be able to get to it for well over a year. Subsequently, I called John Milius and asked if he wanted to direct it, and John was also disposed on another project. Then I thought maybe if I directed it myself as a big action war film, American Zoetrope could make a lot of money which we could use to make our small personal films.”

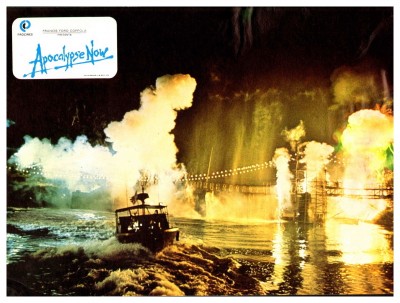

Coppola and Zoetrope assembled US$8.5 million from foreign distributors, United Artists gave them an extra US$7.5 million on the basis that the film would star Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen and Gene Hackman. When Coppola couldn’t convince McQueen or Hackman to shoot in the Philippines, he cast Harvey Keitel as Captain Willard, the assassin sent up the river to ‘terminate with extreme prejudice’ the renegade Colonel Kurtz. If Apocalypse Now is a horrifying operatic epic, so too was the making of the movie. Coppola began the film as an Oscar-winning director at the height of his powers. Before he was finished, he would refer to it as the ‘Idiodyssey’: “Like Captain Willard, I was moving up a river in a faraway jungle, looking for answers and hoping for some kind of catharsis. We made Apocalypse the way Americans made war in Vietnam – there were too many of us, too much money and equipment – and little by little, we went insane.”

Coppola and Zoetrope assembled US$8.5 million from foreign distributors, United Artists gave them an extra US$7.5 million on the basis that the film would star Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen and Gene Hackman. When Coppola couldn’t convince McQueen or Hackman to shoot in the Philippines, he cast Harvey Keitel as Captain Willard, the assassin sent up the river to ‘terminate with extreme prejudice’ the renegade Colonel Kurtz. If Apocalypse Now is a horrifying operatic epic, so too was the making of the movie. Coppola began the film as an Oscar-winning director at the height of his powers. Before he was finished, he would refer to it as the ‘Idiodyssey’: “Like Captain Willard, I was moving up a river in a faraway jungle, looking for answers and hoping for some kind of catharsis. We made Apocalypse the way Americans made war in Vietnam – there were too many of us, too much money and equipment – and little by little, we went insane.”

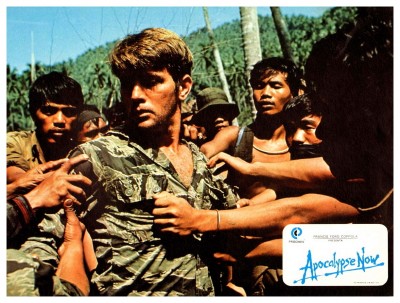

Coppola arrived in Manila on the 1st of March 1976 with his wife Eleanor, their three children, his nephew, projectionist, housekeeper and babysitter. Less than three weeks later the shoot began. Coppola immediately ran into problems with his lead actor Harvey Keitel, who found it difficult to play Willard as a passive onlooker. Upon viewing rushes, Coppola hurriedly flew back to Los Angeles and replaced Keitel with Martin Sheen. The production continued to be beset with problems. On the 26th of May a major typhoon destroyed the Playmate set, forcing the production to shut down for six weeks. The delay gave Coppola some breathing room, and wife Eleanor continued to write production notes: “He couldn’t go on making the original John Milius script because it didn’t really express his ideas, and he couldn’t stop because so much money had been spent. He was really scared and miserable, and at just that moment the typhoon came along and gave him the excuse to stop and try to resolve his conflict.”

Coppola arrived in Manila on the 1st of March 1976 with his wife Eleanor, their three children, his nephew, projectionist, housekeeper and babysitter. Less than three weeks later the shoot began. Coppola immediately ran into problems with his lead actor Harvey Keitel, who found it difficult to play Willard as a passive onlooker. Upon viewing rushes, Coppola hurriedly flew back to Los Angeles and replaced Keitel with Martin Sheen. The production continued to be beset with problems. On the 26th of May a major typhoon destroyed the Playmate set, forcing the production to shut down for six weeks. The delay gave Coppola some breathing room, and wife Eleanor continued to write production notes: “He couldn’t go on making the original John Milius script because it didn’t really express his ideas, and he couldn’t stop because so much money had been spent. He was really scared and miserable, and at just that moment the typhoon came along and gave him the excuse to stop and try to resolve his conflict.”

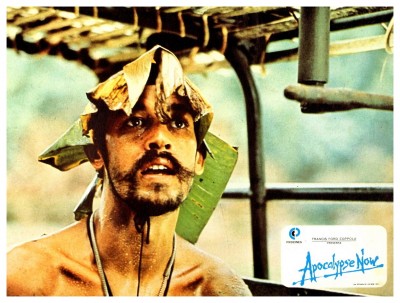

The way Coppola chose to resolve his conflict was to embark on a series of script rewrites which continued when production recommenced. Coppola often rewrote scenes for the next day late into the night on 3×5 cards. Actors would get call sheets for the next day’s work that read ‘scenes unknown’. Brando arrived on the 31st of August, but massively overweight and completely unprepared. Despite initial misgivings by both Coppola and Brando, the pair were able to use this to the film’s advantage. Kurtz was a massive figure, his size equal to his legend, lurking in the shadows, and Brando’s wild improvisations helped Coppola discover the ending he had been searching for. But the endless shoot was taking a terrible toll on cast and crew, and none felt it so strongly as Martin Sheen. On the evening of the 5th of March 1977, Sheen suffered a serious heart attack and was in the throes of a nervous breakdown: “I completely fell apart, my spirit was exposed. I cried and cried. I turned grey – my eyes, my beard – all grey.” A priest even read Sheen his last rites. In order to keep shooting, Coppola brought in Sheen’s brother to the Philippines and shot him as his double while Sheen recuperated. Less than two months later, Sheen was back at work.

The way Coppola chose to resolve his conflict was to embark on a series of script rewrites which continued when production recommenced. Coppola often rewrote scenes for the next day late into the night on 3×5 cards. Actors would get call sheets for the next day’s work that read ‘scenes unknown’. Brando arrived on the 31st of August, but massively overweight and completely unprepared. Despite initial misgivings by both Coppola and Brando, the pair were able to use this to the film’s advantage. Kurtz was a massive figure, his size equal to his legend, lurking in the shadows, and Brando’s wild improvisations helped Coppola discover the ending he had been searching for. But the endless shoot was taking a terrible toll on cast and crew, and none felt it so strongly as Martin Sheen. On the evening of the 5th of March 1977, Sheen suffered a serious heart attack and was in the throes of a nervous breakdown: “I completely fell apart, my spirit was exposed. I cried and cried. I turned grey – my eyes, my beard – all grey.” A priest even read Sheen his last rites. In order to keep shooting, Coppola brought in Sheen’s brother to the Philippines and shot him as his double while Sheen recuperated. Less than two months later, Sheen was back at work.

Coppola finished the shoot in mid-May 1977, the figures speak of a war of attrition. The shoot had been scheduled to last four months, but continued for fifteen. In total Coppola shot two million feet (370 hours) of film over 238 days, and the budget had ballooned out to US$27 million. Surely the worst part was over, right? Unfortunately, no. If the shoot was grueling, the post-production was even more so. Coppola was struggling to unify the different sections of Willard’s journey when he decided to take another approach and make each scene stylistically self-contained. To link them together he revisited an idea he had originally abandoned as ‘pedestrian’ and hired Dispatches author Michael Herr to write voice-over narration for Willard. The atmosphere in the edit room grew so crazy that one assistant editor became obsessed with the film to the point that he would sneak into the editing suite at night and rework the footage. When Coppola told him to stop, the assistant editor stole reels of the film, burnt them and sent Coppola the ashes.

Coppola finished the shoot in mid-May 1977, the figures speak of a war of attrition. The shoot had been scheduled to last four months, but continued for fifteen. In total Coppola shot two million feet (370 hours) of film over 238 days, and the budget had ballooned out to US$27 million. Surely the worst part was over, right? Unfortunately, no. If the shoot was grueling, the post-production was even more so. Coppola was struggling to unify the different sections of Willard’s journey when he decided to take another approach and make each scene stylistically self-contained. To link them together he revisited an idea he had originally abandoned as ‘pedestrian’ and hired Dispatches author Michael Herr to write voice-over narration for Willard. The atmosphere in the edit room grew so crazy that one assistant editor became obsessed with the film to the point that he would sneak into the editing suite at night and rework the footage. When Coppola told him to stop, the assistant editor stole reels of the film, burnt them and sent Coppola the ashes.

The endless delays drew the ire of United Artists, who saw the chances of recouping their investment dwindling by the day. A studio screening of the work in progress disappointed Coppola when the Ride Of The Valkyries scene drew the most praise from the executives: “The film reaches the highest level during the f*cking helicopter battle! My nerves are shot, my heart is broken, my imagination is dead.” Nonetheless, Coppola continued to work hard through the American summer of 1978, only to see his film beaten to the box-office by Michael Cimino‘s Vietnam war drama The Deer Hunter (1979). The critical and commercial success of The Deer Hunter proved there was an audience for hard-hitting films about the Vietnam war, raising the stakes higher for Coppola. The premiere was postponed from December 1977 to May 1978 to September 1978 to May 1979, when it was screened in an incomplete version at the Cannes Film Festival. The screening was a huge success, and Apocalypse Now shared the Palme d’Or with Volker Schlondorff‘s The Tin Drum (1979).

The endless delays drew the ire of United Artists, who saw the chances of recouping their investment dwindling by the day. A studio screening of the work in progress disappointed Coppola when the Ride Of The Valkyries scene drew the most praise from the executives: “The film reaches the highest level during the f*cking helicopter battle! My nerves are shot, my heart is broken, my imagination is dead.” Nonetheless, Coppola continued to work hard through the American summer of 1978, only to see his film beaten to the box-office by Michael Cimino‘s Vietnam war drama The Deer Hunter (1979). The critical and commercial success of The Deer Hunter proved there was an audience for hard-hitting films about the Vietnam war, raising the stakes higher for Coppola. The premiere was postponed from December 1977 to May 1978 to September 1978 to May 1979, when it was screened in an incomplete version at the Cannes Film Festival. The screening was a huge success, and Apocalypse Now shared the Palme d’Or with Volker Schlondorff‘s The Tin Drum (1979).

While Cannes kudos meant little at the American box-office, the tide of criticism began to turn. The many postponements caused the film to be mocked in the press as ‘Apocalypse When?’ but when Apocalypse Now finally saw international release in August 1979, the film was an instant hit – to the surprise and relief of the studios and critics alike. Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote, “Some ultimate and flawed perfection may have been narrowly missed. But as a noble use of the medium and as a tireless expression of a national anguish, it towers over everything that has been attempted by an American filmmaker in a very long time.” And it’s with that thought-provoking note that I’ll ask you to please join me next time when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of film and television, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

While Cannes kudos meant little at the American box-office, the tide of criticism began to turn. The many postponements caused the film to be mocked in the press as ‘Apocalypse When?’ but when Apocalypse Now finally saw international release in August 1979, the film was an instant hit – to the surprise and relief of the studios and critics alike. Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote, “Some ultimate and flawed perfection may have been narrowly missed. But as a noble use of the medium and as a tireless expression of a national anguish, it towers over everything that has been attempted by an American filmmaker in a very long time.” And it’s with that thought-provoking note that I’ll ask you to please join me next time when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of film and television, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews