“It is the height of the war in Vietnam, and US Army Captain Willard is sent by Colonel Lucas and a General to carry out a mission that officially ‘does not exist, nor will it ever exist’. The mission: To seek out a mysterious Green Beret Colonel, Walter Kurtz, whose army has crossed the border into Cambodia and is conducting hit-and-run missions against the Viet Cong and NVA. The army believes Kurtz has gone completely insane and Willard’s job is to eliminate him! Willard, sent up the Nung River on a US Navy patrol boat, discovers that his target is one of the most decorated officers in the US Army. His crew meets up with surfer-type Lt. Colonel Kilgore, head of a US Army helicopter cavalry group which eliminates a Viet Cong outpost to provide an entry point into the Nung River. After some hair-raising encounters, in which some of his crew are killed, Willard, Lance and Chef reach Colonel Kurtz’s outpost, beyond the Do Lung Bridge. Now, after becoming prisoners of Kurtz, will Willard and the others be able to fulfill their mission?” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

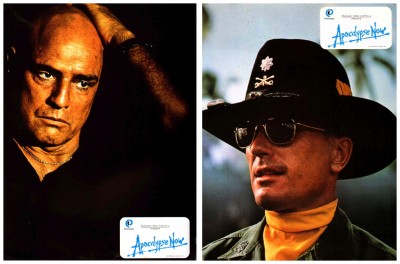

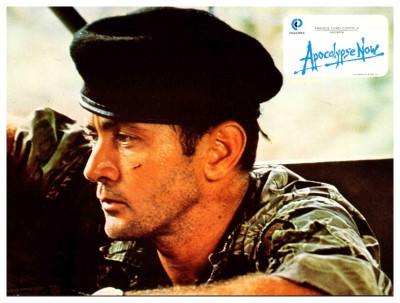

Francis Ford Coppola‘s epic about the madness and horror of the Vietnam war was always considered controversial, yet there is no truly volatile material. Critics and moviegoers may have second-guessed or applauded Coppola’s choices as a filmmaker (especially considering that he filmed two endings), but the only cause for debate among people interested in the war itself is Coppola’s best, most authentic sequence: Stoned leaderless soldiers fighting continuously behind enemy lines while headquarters has forgotten about them. The story, inspired by the Joseph Conrad novel Heart Of Darkness, has the United States military sending agent Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) into the North Vietnam wilderness to kill United States officer Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who has become the god-like leader of a renegade band of natives. On his journey upriver, Willard experiences the surreal sights and sounds of the war, and comes across the lunatic fringe of the American military, including officer Kilgore (Robert Duvall), who plays Wagner’s Ride Of The Valkyries at full volume while leading bombing raids.

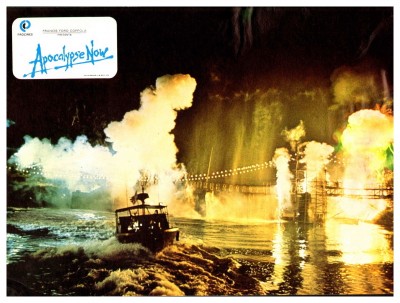

Many of the visuals are very exciting, but the movie can be annoyingly self-conscious – too often Coppola seems to be calling attention to his own artistry and imagination, and the boat trip comes across a little like a theme park ride in which every turn of the river reveals a new tableau. Furthermore, the scene in which Willard and Kurtz lie around philosophising while Coppola gets super-pretentious with his camera and character placement recalls the similarly shot ultra-boring scene of Liv Ullmann and Ingrid Bergman in Ingmar Bergman‘s Autumn Sonata (1978). If anything, Apocalypse Now (1979) is a self-important allegorical epic and in many respects succeeds as an ambitious albeit muddled criticism of America’s military involvement in Vietnam. Given the current climate of sanitised big-budget movies coming out of Hollywood, Coppola’s sprawling masterpiece – above all else – remains a staggering technical achievement from a bygone era in American cinema when ideas were still regarded as a necessary component for the making of a movie.

Many of the visuals are very exciting, but the movie can be annoyingly self-conscious – too often Coppola seems to be calling attention to his own artistry and imagination, and the boat trip comes across a little like a theme park ride in which every turn of the river reveals a new tableau. Furthermore, the scene in which Willard and Kurtz lie around philosophising while Coppola gets super-pretentious with his camera and character placement recalls the similarly shot ultra-boring scene of Liv Ullmann and Ingrid Bergman in Ingmar Bergman‘s Autumn Sonata (1978). If anything, Apocalypse Now (1979) is a self-important allegorical epic and in many respects succeeds as an ambitious albeit muddled criticism of America’s military involvement in Vietnam. Given the current climate of sanitised big-budget movies coming out of Hollywood, Coppola’s sprawling masterpiece – above all else – remains a staggering technical achievement from a bygone era in American cinema when ideas were still regarded as a necessary component for the making of a movie.

Fast-forward two decades later, and Coppola finds himself in a London hotel room with nothing to do: “I noticed Apocalypse Now was going to be on television and I always enjoyed the opening, so I started watching and I ended up seeing the whole movie. What struck me was this film, which had been so demanding, strange and adventurous when it first came out, now seemed like something that the audience had caught up to. That encouraged me to go back and try a new version. I thought, now that the film has been around for a while and has become something of a classic, we could edit it with more attention to what the themes are.” His first call was to editor Walter Murch and together they started to edit the new version of the movie from scratch. Rather than simply reinserting the deleted scenes taken out of the film during the original editorial process, they re-edited the film from the original unedited raw footage and dailies.

Fast-forward two decades later, and Coppola finds himself in a London hotel room with nothing to do: “I noticed Apocalypse Now was going to be on television and I always enjoyed the opening, so I started watching and I ended up seeing the whole movie. What struck me was this film, which had been so demanding, strange and adventurous when it first came out, now seemed like something that the audience had caught up to. That encouraged me to go back and try a new version. I thought, now that the film has been around for a while and has become something of a classic, we could edit it with more attention to what the themes are.” His first call was to editor Walter Murch and together they started to edit the new version of the movie from scratch. Rather than simply reinserting the deleted scenes taken out of the film during the original editorial process, they re-edited the film from the original unedited raw footage and dailies.

According to Walter Murch, the entire process including editing and sound remixing took from March through to August of 2000: “There was a certain part of me that was agitated about going back into the jungle. I had spent two challenging, draining years of my life on this already, and I knew we were up against an original assembly that ran for more than five hours, and in dailies some 1.25 million feet of film. The film and magnetic track alone weighed seven tons. But about ten days into the process, it felt perfectly natural.” The main attraction to Apocalypse Now Redux is the additional footage – fourteen scenes by my count – excised from the original release and restored here by Coppola and Murch. Inasmuch as the scenes remain interesting, even anecdotal events from the notorious production, they seem to have been dug up as marketing tools rather than aesthetic improvements, as the extra Playboy bunnies (Cynthia Wood, Colleen Camp, Linda Carpenter) footage demonstrates.

According to Walter Murch, the entire process including editing and sound remixing took from March through to August of 2000: “There was a certain part of me that was agitated about going back into the jungle. I had spent two challenging, draining years of my life on this already, and I knew we were up against an original assembly that ran for more than five hours, and in dailies some 1.25 million feet of film. The film and magnetic track alone weighed seven tons. But about ten days into the process, it felt perfectly natural.” The main attraction to Apocalypse Now Redux is the additional footage – fourteen scenes by my count – excised from the original release and restored here by Coppola and Murch. Inasmuch as the scenes remain interesting, even anecdotal events from the notorious production, they seem to have been dug up as marketing tools rather than aesthetic improvements, as the extra Playboy bunnies (Cynthia Wood, Colleen Camp, Linda Carpenter) footage demonstrates.

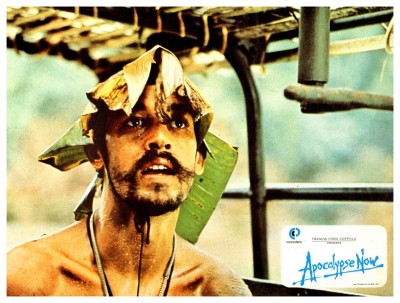

Other restored scenes include the much-discussed French plantation sequence, which includes a riverside encounter, the funeral of Tyrone ‘Clean’ Miller (Laurence Fishburne), a rancorous dinner, and Willard’s seduction of – and by – a young French widow named Roxanne (Aurore Clement). In fact, all the female characters are given nothing substantial to do other than disrobe and, while one could argue that this movie is about men, Coppola continually evades a more intimate portrait of humanity with his enamored sense of grandiose mythology: Kurtz’s compound, a hieroglyphic shrine to Hollywood primitivism, is less affecting for its headless corpses and pagan iconography than it is for an unbearable Dennis Hopper as an unnamed photojournalist, starved of cigarettes but obviously equipped with a full supply of drugs.

Other restored scenes include the much-discussed French plantation sequence, which includes a riverside encounter, the funeral of Tyrone ‘Clean’ Miller (Laurence Fishburne), a rancorous dinner, and Willard’s seduction of – and by – a young French widow named Roxanne (Aurore Clement). In fact, all the female characters are given nothing substantial to do other than disrobe and, while one could argue that this movie is about men, Coppola continually evades a more intimate portrait of humanity with his enamored sense of grandiose mythology: Kurtz’s compound, a hieroglyphic shrine to Hollywood primitivism, is less affecting for its headless corpses and pagan iconography than it is for an unbearable Dennis Hopper as an unnamed photojournalist, starved of cigarettes but obviously equipped with a full supply of drugs.

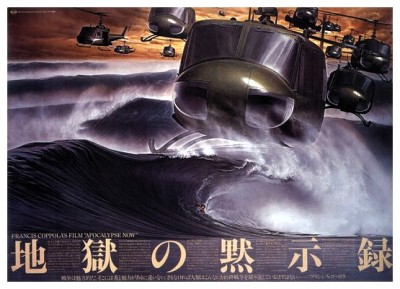

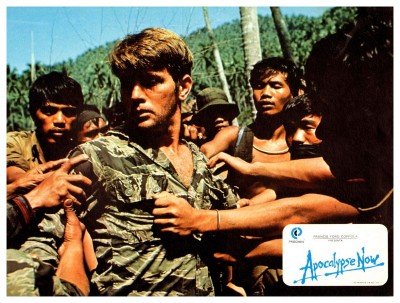

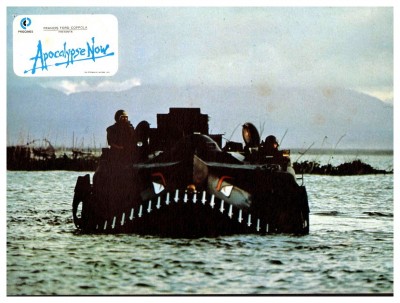

In this psychedelic environment the story (co-scripted by John Milius) concerns Captain Willard, a military burn-out sent up the river on a patrol boat to assassinate a renegade soldier, Colonel Kurtz. Willard’s journey takes on the elements of a detective thriller as he attempts to understand the reasoning behind his mission and the man he’s been sent to kill. Michael Herr‘s superbly written hard-boiled voiceover furthers this mysterious atmosphere: “Everyone gets what he wants. I wanted a mission and, for my sins, they gave me one.” Willard ventures towards Cambodia with an inexperienced ramshackle crew in a compelling journey that is pieced together by a series of surreal vignettes. Undoubtedly, the highlight is a ballistic sequence incorporating an aerial assault on a village featuring a fleet of helicopters and the charismatic surfing-obsessed gung-ho Lt. Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall). Delivering lines like “I love the smell of napalm in the morning,” Duvall once again proves himself not only as one of the finest leading men in the world, but an intuitive actor who can take a cartoonish supporting role and turn it into an awe-inspiring performance of virile magnetism when allowed to use his most potent weapon – his voice.

In this psychedelic environment the story (co-scripted by John Milius) concerns Captain Willard, a military burn-out sent up the river on a patrol boat to assassinate a renegade soldier, Colonel Kurtz. Willard’s journey takes on the elements of a detective thriller as he attempts to understand the reasoning behind his mission and the man he’s been sent to kill. Michael Herr‘s superbly written hard-boiled voiceover furthers this mysterious atmosphere: “Everyone gets what he wants. I wanted a mission and, for my sins, they gave me one.” Willard ventures towards Cambodia with an inexperienced ramshackle crew in a compelling journey that is pieced together by a series of surreal vignettes. Undoubtedly, the highlight is a ballistic sequence incorporating an aerial assault on a village featuring a fleet of helicopters and the charismatic surfing-obsessed gung-ho Lt. Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall). Delivering lines like “I love the smell of napalm in the morning,” Duvall once again proves himself not only as one of the finest leading men in the world, but an intuitive actor who can take a cartoonish supporting role and turn it into an awe-inspiring performance of virile magnetism when allowed to use his most potent weapon – his voice.

Following this chaotic beachfront episode, one of the first conspicuous additions the Redux narrative eventuates: The surf is blown out by a sudden wind-change due to the napalm used, and Willard and Lance (Sam Bottoms) steal Kilgore’s surfboard. Presumably from here the men on the patrol boat are chased up the river by the Colonel in a helicopter, who bellows from a bullhorn about the whereabouts of his Malibu surfboard. While the tone of this three-hour epic is still beguiling, pretentious, symbolic and sinister, lighthearted strokes such as these make a mockery of Coppola’s expensive myopic vision. Situated just as uncomfortably in the narrative is the inclusion of the French plantation scenes involving a community of French ex-patriots refusing to move on historical grounds. Here an agonising funeral is punctuated with the symbolic handing-over of a tattered American flag, while a sensuous and equally extraneous scene takes place between Willard and Roxanne, after they smoke opium and discuss the primeval duality of man. She casually undresses in front of the comatose Captain while seductively deploying the mosquito netting around their lavish-looking bed.

Following this chaotic beachfront episode, one of the first conspicuous additions the Redux narrative eventuates: The surf is blown out by a sudden wind-change due to the napalm used, and Willard and Lance (Sam Bottoms) steal Kilgore’s surfboard. Presumably from here the men on the patrol boat are chased up the river by the Colonel in a helicopter, who bellows from a bullhorn about the whereabouts of his Malibu surfboard. While the tone of this three-hour epic is still beguiling, pretentious, symbolic and sinister, lighthearted strokes such as these make a mockery of Coppola’s expensive myopic vision. Situated just as uncomfortably in the narrative is the inclusion of the French plantation scenes involving a community of French ex-patriots refusing to move on historical grounds. Here an agonising funeral is punctuated with the symbolic handing-over of a tattered American flag, while a sensuous and equally extraneous scene takes place between Willard and Roxanne, after they smoke opium and discuss the primeval duality of man. She casually undresses in front of the comatose Captain while seductively deploying the mosquito netting around their lavish-looking bed.

Like most of his early work as an actor, Martin Sheen is a charismatic presence who can say more with his eyes than many actors can with a two-page monologue. Harnessing these qualities, Coppola works wonders by placing his lead actor on the periphery of the action as a quietly intense observer. Moreover, Coppola’s tour-de-force opening featuring double-exposures and triple-dissolves of helicopters buzzing across both a firestorm and Willard’s face, sets the tone for the wonderfully orchestrated action sequences and Vittorio Storaro‘s jaw-dropping photography. With the interiors just as spectacular as the exteriors, Storaro’s photography is preserved in stunning detail by one of the the most impressive transfers likely to be seen on a DVD this decade. Having previously served Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci brilliantly on smaller-scale movies, Storaro blossoms here under Coppola’s big-budget production values. The kaleidoscopic movement he achieves across Brando’s glistening skull during the actor’s introspective and anticipated entrance help compensate for a glaringly dead-end conclusion to the journey.

Like most of his early work as an actor, Martin Sheen is a charismatic presence who can say more with his eyes than many actors can with a two-page monologue. Harnessing these qualities, Coppola works wonders by placing his lead actor on the periphery of the action as a quietly intense observer. Moreover, Coppola’s tour-de-force opening featuring double-exposures and triple-dissolves of helicopters buzzing across both a firestorm and Willard’s face, sets the tone for the wonderfully orchestrated action sequences and Vittorio Storaro‘s jaw-dropping photography. With the interiors just as spectacular as the exteriors, Storaro’s photography is preserved in stunning detail by one of the the most impressive transfers likely to be seen on a DVD this decade. Having previously served Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci brilliantly on smaller-scale movies, Storaro blossoms here under Coppola’s big-budget production values. The kaleidoscopic movement he achieves across Brando’s glistening skull during the actor’s introspective and anticipated entrance help compensate for a glaringly dead-end conclusion to the journey.

The special features attached to the DVD release of Apocalypse Now Redux include retrospective interviews with the boat crew including Albert Hall, Frederick Forrest, Sam Bottoms and Laurence Fishburne, who was only fourteen years old at the time. There’s a short documentary entitled Apocalypse Then And Now which begins with Coppola being interviewed by the late Roger Ebert at Cannes, and concludes with a brief and perfunctory investigation into the sound remix by Walter Murch. The real highlight is Destruction Of The Kurtz Compound with a commentary by Coppola on his reasons for leaving out this spectacular sequence which Vittorio Storaro claimed to be the best thing he’d ever shot. Coming from the man who lensed The Conformist (1970) and The Bird With The Crystal Plumage (1970), you can be sure this sequence is as good as it sounds. Insofar as Coppola fails to rise to the gauntlet of challenges Apocalypse Now Redux presents, he thankfully doesn’t falter when it comes to providing a thought-provoking movie and, as far as exhilarating experiences go, they just don’t make ’em like this anymore. And it’s with that thought in mind I bid you farewell, and please join me again next week as we see what the postman leaves on my doorstep – and sets on fire – in Horror News! Toodles!

The special features attached to the DVD release of Apocalypse Now Redux include retrospective interviews with the boat crew including Albert Hall, Frederick Forrest, Sam Bottoms and Laurence Fishburne, who was only fourteen years old at the time. There’s a short documentary entitled Apocalypse Then And Now which begins with Coppola being interviewed by the late Roger Ebert at Cannes, and concludes with a brief and perfunctory investigation into the sound remix by Walter Murch. The real highlight is Destruction Of The Kurtz Compound with a commentary by Coppola on his reasons for leaving out this spectacular sequence which Vittorio Storaro claimed to be the best thing he’d ever shot. Coming from the man who lensed The Conformist (1970) and The Bird With The Crystal Plumage (1970), you can be sure this sequence is as good as it sounds. Insofar as Coppola fails to rise to the gauntlet of challenges Apocalypse Now Redux presents, he thankfully doesn’t falter when it comes to providing a thought-provoking movie and, as far as exhilarating experiences go, they just don’t make ’em like this anymore. And it’s with that thought in mind I bid you farewell, and please join me again next week as we see what the postman leaves on my doorstep – and sets on fire – in Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews