SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Taylor and two other astronauts come out of deep hibernation to find that their ship has crashed. Escaping with little more than clothes they find that they have landed on a planet where men are pre-lingual and uncivilized while apes have learned speech and technology. Taylor is captured and taken to the city of the apes after damaging his throat so that he is silent and cannot communicate with the apes.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

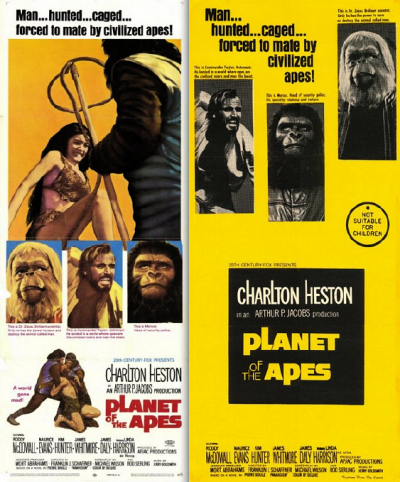

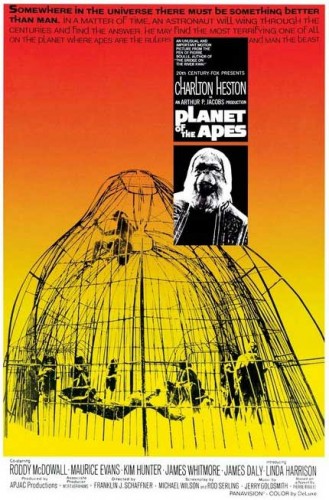

Superficially childish, but in many ways very grown-up, was Planet Of The Apes (1968), one of the two commercial American-made science fiction blockbusters of the year – the other being Charly (1968) starring Cliff Robertson. The French had a hand in this as well, for it was based on Monkey Planet, a rather ordinary satirical novel by the popular French novelist Pierre Boulle, author of The Bridge On The River Kwai (1957). The director, Franklin J. Schaffner, probably had no real affinity with science fiction, though he later made another science fiction movie, The Boys From Brazil (1978). What Schaffner could do, with forcefulness and insight, was to show the clash of strong self-willed men with the worlds in which they find themselves, other examples of his work being The War Lord (1965) and Patton (1970).

Charlton Heston leads a small band of astronauts which crash-lands on an apparently alien planet, where the dominant races are all apes (gorillas, chimpanzees and orangutangs, each with a different cultural function), and humans are a sub-normal slave class. Bare-chested Chuck is a solid, muscular hero and he’s a good choice to play a symbol of human superiority who is humbled when he is to be experimented on by the apes, just as humans experimented on apes back home. The politically-conservative Chuck would go on to star in other liberal-slanted science fiction films including The Omega Man (1971) and Soylent Green (1973), finally making an ironic appearance in the Tim Burton remake of Planet Of The Apes (2001) as an old gorilla who damns all humans and their weapons.

Charlton Heston leads a small band of astronauts which crash-lands on an apparently alien planet, where the dominant races are all apes (gorillas, chimpanzees and orangutangs, each with a different cultural function), and humans are a sub-normal slave class. Bare-chested Chuck is a solid, muscular hero and he’s a good choice to play a symbol of human superiority who is humbled when he is to be experimented on by the apes, just as humans experimented on apes back home. The politically-conservative Chuck would go on to star in other liberal-slanted science fiction films including The Omega Man (1971) and Soylent Green (1973), finally making an ironic appearance in the Tim Burton remake of Planet Of The Apes (2001) as an old gorilla who damns all humans and their weapons.

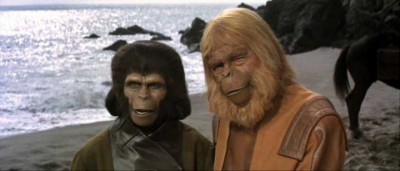

Anyway, the resulting story has become deservedly famous, especially for the wonderfully adroit use in its closing stages of the old science fiction cliche, the half-buried Statue Of Liberty. It projects from the sand like an eroded memory, and shows that this alien planet is really Earth in the far future. The harsh settings, obviously Arizona and Utah desert landscapes, are still notably effective, as are the now-celebrated ape makeup by John Chambers, who entered the special effects pantheon through his creation of these brilliantly mobile and convincing masks.

Anyway, the resulting story has become deservedly famous, especially for the wonderfully adroit use in its closing stages of the old science fiction cliche, the half-buried Statue Of Liberty. It projects from the sand like an eroded memory, and shows that this alien planet is really Earth in the far future. The harsh settings, obviously Arizona and Utah desert landscapes, are still notably effective, as are the now-celebrated ape makeup by John Chambers, who entered the special effects pantheon through his creation of these brilliantly mobile and convincing masks.

Where the film comes unstuck is, perhaps, through being over-ambitious. The script tries to have it both ways. At times ape society is seen as a satirical reflection of all the worst excesses of human society – its racism, its snobbery, its unthinking cruelty. Conversely, at other times the apes sensitivity is supposed to throw a cold light on human insensitivity – we are meant to wonder if perhaps the apes have made a better fist of things than we ever did. This aspect of the film is stressed in the four sequels, whose view of ape life is consistently more sentimental than that of the original.

Where the film comes unstuck is, perhaps, through being over-ambitious. The script tries to have it both ways. At times ape society is seen as a satirical reflection of all the worst excesses of human society – its racism, its snobbery, its unthinking cruelty. Conversely, at other times the apes sensitivity is supposed to throw a cold light on human insensitivity – we are meant to wonder if perhaps the apes have made a better fist of things than we ever did. This aspect of the film is stressed in the four sequels, whose view of ape life is consistently more sentimental than that of the original.

As a piece of action-adventure cinema, Planet Of The Apes is quite slick and competent, but as science fiction it’s rather illogical at times. The plot revolves around the fact that astronaut Chuck doesn’t realise until the very end that the ape world is really the Earth of the future, a future where the apes have evolved to become the dominant species – despite the fact that he heard them speak English. Nor are the apes unduly surprised when they hear him speak English, they’re only surprised he can talk at all. Yet the film became one of the most popular science fiction films of all-time, spawning four sequels, two television series and a big-budget remake, and its success demonstrates that despite the increasing sophistication of science fiction movies during the sixties, the general public still didn’t understand what science fiction was all about.

As a piece of action-adventure cinema, Planet Of The Apes is quite slick and competent, but as science fiction it’s rather illogical at times. The plot revolves around the fact that astronaut Chuck doesn’t realise until the very end that the ape world is really the Earth of the future, a future where the apes have evolved to become the dominant species – despite the fact that he heard them speak English. Nor are the apes unduly surprised when they hear him speak English, they’re only surprised he can talk at all. Yet the film became one of the most popular science fiction films of all-time, spawning four sequels, two television series and a big-budget remake, and its success demonstrates that despite the increasing sophistication of science fiction movies during the sixties, the general public still didn’t understand what science fiction was all about.

But this is to quibble. The firmly-directed, fast-moving story sweeps away most of these objections, and while the black jokes may not make coherent sense overall, most of them work individually. In fact, Planet Of The Apes is rather disturbing, there is nothing comfortable about it. Indeed, its cold view of human/ape evolution was a real step forward in relation to the intricacy of the subjects that science fiction cinema was prepared to contemplate. The old idea that capitalism and the American way of life was bound to be the cultural norm for millennia to come was given a severe bruising by this film, and its popular success showed that maybe the old taboos (the suggestion that mankind is not the peak of creation) could be profitably broken. The decade of Vietnam, during which this film was made, was stimulating a useful self-doubt among people everywhere.

But this is to quibble. The firmly-directed, fast-moving story sweeps away most of these objections, and while the black jokes may not make coherent sense overall, most of them work individually. In fact, Planet Of The Apes is rather disturbing, there is nothing comfortable about it. Indeed, its cold view of human/ape evolution was a real step forward in relation to the intricacy of the subjects that science fiction cinema was prepared to contemplate. The old idea that capitalism and the American way of life was bound to be the cultural norm for millennia to come was given a severe bruising by this film, and its popular success showed that maybe the old taboos (the suggestion that mankind is not the peak of creation) could be profitably broken. The decade of Vietnam, during which this film was made, was stimulating a useful self-doubt among people everywhere.

If audiences were prepared to swallow this pill without too much sugar coating on it, then perhaps the tough-mindedness of so much science fiction in written form could be imported into the cinema as well. This mood of greater maturity was to continue, waveringly, for another decade before being swept away by the entertaining simplicities of Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977). Anyway, please join me next week so I can poke you in the eye with another frightful excursion to the backside of the Public Domain, filmed in glorious 2-D black & white Regularscope for…Horror News! Toodles!

If audiences were prepared to swallow this pill without too much sugar coating on it, then perhaps the tough-mindedness of so much science fiction in written form could be imported into the cinema as well. This mood of greater maturity was to continue, waveringly, for another decade before being swept away by the entertaining simplicities of Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977). Anyway, please join me next week so I can poke you in the eye with another frightful excursion to the backside of the Public Domain, filmed in glorious 2-D black & white Regularscope for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews