“Legal and illegal criminality. An American tourist with a boat is robbed by a gang of teenager boys, assisted by the leader’s sister. But soon afterward she jumps to the victim’s boat to escape her brother’s incestuous jealousy. The couple fly together and is hunted by the entire gang. Both happen to enter high-classified military territory. There might be a third and atomic world war, after which no ordinary man could survive. But now and then children are born who are ‘naturally’ radioactive and have cold blood. They might survive in the post-war world and carry on mankind. They are fetched and brought to an underground construction where they are educated by TV. They are told that they are on a space ship moving toward the earth, which they should eventually colonize. This military project seems to be a failure because of a high mortality among the children. The military soon finds the gang. The couple finds the children and tries to help them to escape. This situation will develop into psychological and other horror.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

During and after the Vietnam war, the image of our bodies as intensely vulnerable to decay and mutilation reached its climax – or nadir – in the work of George Romero, David Cronenberg and others. Such images, however, did not spring up by parthenogenesis – they were the wild children of an already existing family of images, a family with a history. Remember when Leo G. Carroll was over a barrel in Tarantula (1955)? His work dreadfully deforms him when he’s forcibly injected with his own serum. He’s an early example of a long cinematic line of victims of technology, people who are rendered into monsters, whose bodies are changed or damaged, sometimes subtly, sometimes horribly. The saddest of all monsters is the one that was once exactly like you or me.

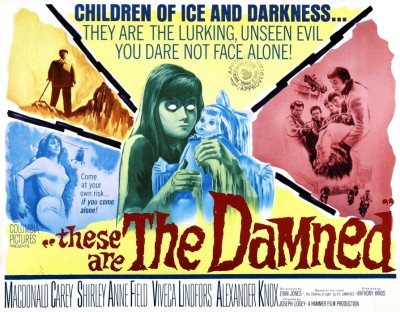

The Fly (1958) went as far as any film of the period in evoking the horror of the body in terms of disgusting metamorphosis. But changes to the body could be much more subtle, and this was the case with The Damned (1963) released in the United States as These Are The Damned, made in 1961 for Hammer Films by the celebrated director Joseph Losey, who was undergoing hard times after his exile from Hollywood as an undesirable Communist sympathiser during the McCarthy period. Apart from concerning an unusual group of children, this film has absolutely nothing to do with John Wyndham‘s novel, though there’s no doubt it was inspired by the success of Village Of The Damned (1960). The Damned, based on the novel The Children Of Light by H.L. Lawrence and scripted by Evan Jones, can be rather pretentious at times.

The Fly (1958) went as far as any film of the period in evoking the horror of the body in terms of disgusting metamorphosis. But changes to the body could be much more subtle, and this was the case with The Damned (1963) released in the United States as These Are The Damned, made in 1961 for Hammer Films by the celebrated director Joseph Losey, who was undergoing hard times after his exile from Hollywood as an undesirable Communist sympathiser during the McCarthy period. Apart from concerning an unusual group of children, this film has absolutely nothing to do with John Wyndham‘s novel, though there’s no doubt it was inspired by the success of Village Of The Damned (1960). The Damned, based on the novel The Children Of Light by H.L. Lawrence and scripted by Evan Jones, can be rather pretentious at times.

The story concerns American Simon Wells (Macdonald Carey) who, while visiting a seedy English seaside resort town, becomes involved with both the sister of the leader of a local gang of young thugs, and a scientist in charge of a secret project being carried out at a nearby military installation. Wells’ relationship with the girl – Shirley Ann Field giving one of the worst performances by an actress in a science fiction film since Ann Robinson in War Of The Worlds (1953) – is bitterly resented by her brother King (Oliver Reed in one of his earliest and most murderous roles). The couple are eventually forced to flee from King and his gang, taking refuge in a cave under the military base, only to discover a group of children living there – children who are incredibly cold to touch.

The story concerns American Simon Wells (Macdonald Carey) who, while visiting a seedy English seaside resort town, becomes involved with both the sister of the leader of a local gang of young thugs, and a scientist in charge of a secret project being carried out at a nearby military installation. Wells’ relationship with the girl – Shirley Ann Field giving one of the worst performances by an actress in a science fiction film since Ann Robinson in War Of The Worlds (1953) – is bitterly resented by her brother King (Oliver Reed in one of his earliest and most murderous roles). The couple are eventually forced to flee from King and his gang, taking refuge in a cave under the military base, only to discover a group of children living there – children who are incredibly cold to touch.

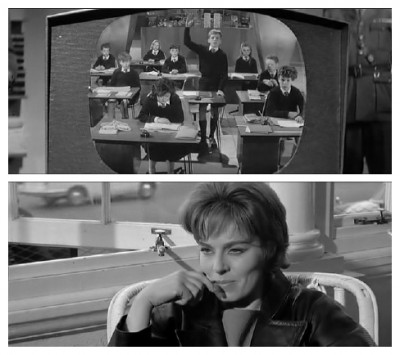

In a secret government experiment, these children have been exposed to radioactivity since birth. Their home is a hidden research installation in caverns off a cliff-face on England’s south coast. Now highly radioactive themselves, they have an amazingly low body temperature, and their education is carried out by closed-circuit television. They have been created as the possible progenitors of a new race of mankind after the present race is destroyed in the expected nuclear holocaust. The image of these icy youngsters is both literally and metaphorically chilling. They don’t completely understand their own predicament, which is that the only world in which they can safely live out their lives is a world destroyed by atomic war. Without understanding the danger to themselves (fatal contamination), the adults try to help the children to escape. The chief scientist Bernard (Alexander Knox), just as cold-blooded as the children, allows this to happen and then has the couple shot from a helicopter that hovers above them like a hawk, in a visually haunting scene, as they try to escape by boat.

In a secret government experiment, these children have been exposed to radioactivity since birth. Their home is a hidden research installation in caverns off a cliff-face on England’s south coast. Now highly radioactive themselves, they have an amazingly low body temperature, and their education is carried out by closed-circuit television. They have been created as the possible progenitors of a new race of mankind after the present race is destroyed in the expected nuclear holocaust. The image of these icy youngsters is both literally and metaphorically chilling. They don’t completely understand their own predicament, which is that the only world in which they can safely live out their lives is a world destroyed by atomic war. Without understanding the danger to themselves (fatal contamination), the adults try to help the children to escape. The chief scientist Bernard (Alexander Knox), just as cold-blooded as the children, allows this to happen and then has the couple shot from a helicopter that hovers above them like a hawk, in a visually haunting scene, as they try to escape by boat.

The distributors, alarmed by the political implications and the fact the film could not be labeled as straight horror, delayed the film’s release for several years, cutting the British print from 96 to 87 minutes and cutting the American print to 77 minutes – Americans being presumably more susceptible to all this Commie propaganda. Even in its ruined state, the film remains a stark, ironic, stylish study in human manipulation, with a number of strong visual symbols, notably the stern, abstractly humanoid sculptures made by Freya Neilson (Viveca Lindfors) who, when she begins to guess what is happening within the bird-haunted cliffs, is ruthlessly executed by the scientist while her statues look on in silent reproach.

The distributors, alarmed by the political implications and the fact the film could not be labeled as straight horror, delayed the film’s release for several years, cutting the British print from 96 to 87 minutes and cutting the American print to 77 minutes – Americans being presumably more susceptible to all this Commie propaganda. Even in its ruined state, the film remains a stark, ironic, stylish study in human manipulation, with a number of strong visual symbols, notably the stern, abstractly humanoid sculptures made by Freya Neilson (Viveca Lindfors) who, when she begins to guess what is happening within the bird-haunted cliffs, is ruthlessly executed by the scientist while her statues look on in silent reproach.

For all of Joseph Losey‘s striving to transform such mediocre material into an important statement on the moral corruption of Western technocracy embellished with evocative imagery, the resulting film’s basic message seems to be that sustained exposure to radiation drastically lowers one’s body temperature and is likely to be harmful in the long run. Keep that thought in mind for the next seven days, and join me again next week so I can poke you in the mind’s eye with another pointed stick from the faggot formerly known as Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

For all of Joseph Losey‘s striving to transform such mediocre material into an important statement on the moral corruption of Western technocracy embellished with evocative imagery, the resulting film’s basic message seems to be that sustained exposure to radiation drastically lowers one’s body temperature and is likely to be harmful in the long run. Keep that thought in mind for the next seven days, and join me again next week so I can poke you in the mind’s eye with another pointed stick from the faggot formerly known as Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews