“Hugo is an orphan boy living in the walls of a train station in 1930s Paris. He learned to fix clocks and other gadgets from his father and uncle which he puts to use keeping the train station clocks running. The only thing that he has left that connects him to his dead father is an automaton (mechanical man) that doesn’t work without a special key which Hugo needs to find to unlock the secret he believes it contains. On his adventures, he meets with a shopkeeper, George Melies, who works in the train station and his adventure-seeking god-daughter. Hugo finds that they have a surprising connection to his father and the automaton, and he discovers it unlocks some memories the old man has buried inside regarding his past.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

The films of Martin Scorsese are extraordinary, there’s no doubt about it but, even though critics count many of them among their favourites of all time, the box-office has not always been kind. Scorsese movies can be as tough as the language in them. Goodfellas (1990), for instance, was essentially a comedy but its violence was a little too much for broad audiences yet, a year later, his remake of the classic Cape Fear (1991) turned out to be a mainstream success but, even there, Scorsese couldn’t resist adding biblical proportions to the revenge thriller. It’s not his fault, it was already in Wesley Strick‘s script, but it tied into his obsessive behaviour with religious themes. Much the same with Boxcar Bertha (1972) – everyone who saw the film assumed the crucifixion of David Carradine at the end was put in by Scorsese, but it was there in the original script – he was simply drawn to it.

Sin and redemption have always had a home in Scorsese’s films, reaching an apparent apex when Willem Dafoe played an all-too-human Jesus in The Last Temptation Of Christ (1988), only to be topped by Robert De Niro‘s divine-avenger figure in Cape Fear. In his first film Who’s That Knocking At My Door (1967), the camera ferrets out the religious paraphernalia in Harvey Keitel‘s life – the holy candle, statues of Mary and Jesus – and shots of Keitel at confession are jarringly juxtaposed against scenes of a rape. Part of what makes Scorsese’s films so disturbing are his attempts to capture a feeling of almost eavesdropping on someone’s private world, and feeling that anxiety of hearing too much and feeling embarrassed by it. A very delicate area indeed, already traversed by Scorsese’s mentor, John Cassavettes. Scorsese has learned not to use the word ‘art’ in conjunction with his movies, simply because he doesn’t want to scare people away who would read certain articles and might want to see the film, but were put-off because they might be seeing an ‘art’ film. Nowadays he just says no, it’s a film of ‘entertainment’.

Sin and redemption have always had a home in Scorsese’s films, reaching an apparent apex when Willem Dafoe played an all-too-human Jesus in The Last Temptation Of Christ (1988), only to be topped by Robert De Niro‘s divine-avenger figure in Cape Fear. In his first film Who’s That Knocking At My Door (1967), the camera ferrets out the religious paraphernalia in Harvey Keitel‘s life – the holy candle, statues of Mary and Jesus – and shots of Keitel at confession are jarringly juxtaposed against scenes of a rape. Part of what makes Scorsese’s films so disturbing are his attempts to capture a feeling of almost eavesdropping on someone’s private world, and feeling that anxiety of hearing too much and feeling embarrassed by it. A very delicate area indeed, already traversed by Scorsese’s mentor, John Cassavettes. Scorsese has learned not to use the word ‘art’ in conjunction with his movies, simply because he doesn’t want to scare people away who would read certain articles and might want to see the film, but were put-off because they might be seeing an ‘art’ film. Nowadays he just says no, it’s a film of ‘entertainment’.

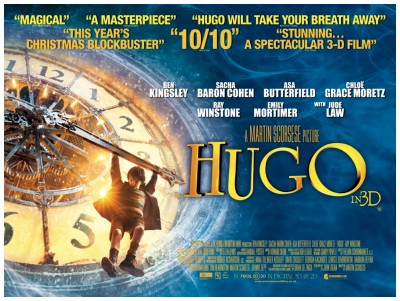

Scorsese is better known for tackling films whose male protagonists are firmly rooted in the underworld, whether the darkness of their mind – Taxi Driver (1976), Shutter Island (2010) – or the world they find themselves in – Raging Bull (1980), The Departed (2006). And while the venerated filmmaker has produced many a hat-trick, Hugo (2011) would have to be the ultimate surprise. A film where the only violence to be seen is a sharp tug on a collar, and where the nastier side of life is naturally inherent but then ever-so-quickly pushed aside by magical imagery or comic relief. And where, oh where is Bobby De Niro?! Or dear Leo DiCaprio?!

Scorsese is better known for tackling films whose male protagonists are firmly rooted in the underworld, whether the darkness of their mind – Taxi Driver (1976), Shutter Island (2010) – or the world they find themselves in – Raging Bull (1980), The Departed (2006). And while the venerated filmmaker has produced many a hat-trick, Hugo (2011) would have to be the ultimate surprise. A film where the only violence to be seen is a sharp tug on a collar, and where the nastier side of life is naturally inherent but then ever-so-quickly pushed aside by magical imagery or comic relief. And where, oh where is Bobby De Niro?! Or dear Leo DiCaprio?!

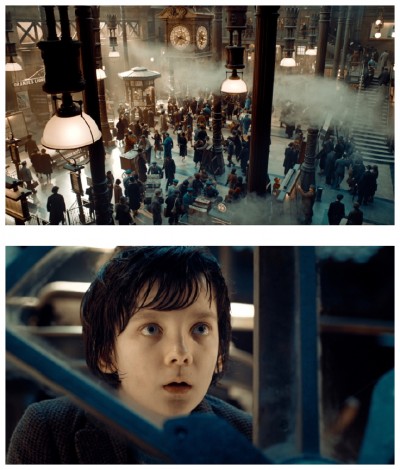

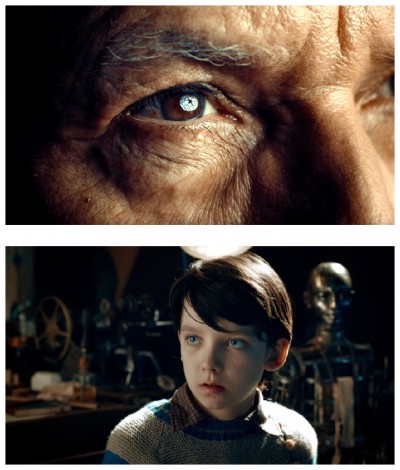

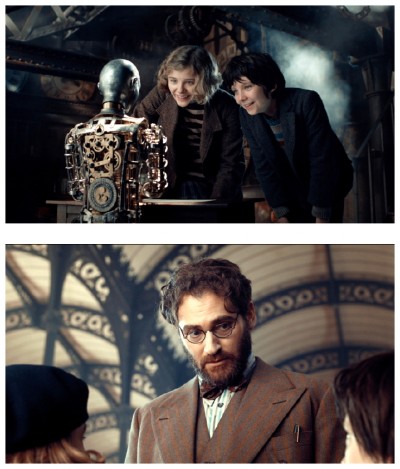

Doll-faced English actor Asa Butterfield – looking a lot like David Bennent in The Tin Drum (1979) – takes the lead role as Hugo who, after the death of his clock-making father (Jude Law), becomes an orphan who lives in a Parisian railway station with his alcoholic uncle (Ray Winstone). The uncle soon flees the scene, leaving Hugo to maintain the clocks in the station. During his down-time the boy steals little gadgets from the local toy-maker Papa Georges (Ben Kingsley) to fix the automaton his father had discovered just before his death. Certain that the automaton contains a message from his father (and as a respite from his loneliness) Hugo becomes obsessed with fixing it. Soon Papa Georges catches him stealing trinkets to make it work, and so begins Scorsese’s tribute to the birth of motion pictures.

Doll-faced English actor Asa Butterfield – looking a lot like David Bennent in The Tin Drum (1979) – takes the lead role as Hugo who, after the death of his clock-making father (Jude Law), becomes an orphan who lives in a Parisian railway station with his alcoholic uncle (Ray Winstone). The uncle soon flees the scene, leaving Hugo to maintain the clocks in the station. During his down-time the boy steals little gadgets from the local toy-maker Papa Georges (Ben Kingsley) to fix the automaton his father had discovered just before his death. Certain that the automaton contains a message from his father (and as a respite from his loneliness) Hugo becomes obsessed with fixing it. Soon Papa Georges catches him stealing trinkets to make it work, and so begins Scorsese’s tribute to the birth of motion pictures.

In Scorsese’s films there are often references to the film industry or small homages to certain mechanisms used within the industry – the heavy symbolism in almost every frame of The Departed, for instance. In the intricate world created in Hugo you can also perceive nods to French cinema, like Jean-Pierre Jeunet, through the little romantic sub-plots unravelling around the main characters, and Sacha Baron Cohen‘s impersonation of Jacques Clouseau. Hugo presents itself like a huge mural: The backdrop and details are so contrived and painstakingly thoughtful that you could sit there and unwrap it for hours. It may appear to be aimed at young audiences, but the story-line traverses so many territories that it would be a shame to pigeon-hole it.

In Scorsese’s films there are often references to the film industry or small homages to certain mechanisms used within the industry – the heavy symbolism in almost every frame of The Departed, for instance. In the intricate world created in Hugo you can also perceive nods to French cinema, like Jean-Pierre Jeunet, through the little romantic sub-plots unravelling around the main characters, and Sacha Baron Cohen‘s impersonation of Jacques Clouseau. Hugo presents itself like a huge mural: The backdrop and details are so contrived and painstakingly thoughtful that you could sit there and unwrap it for hours. It may appear to be aimed at young audiences, but the story-line traverses so many territories that it would be a shame to pigeon-hole it.

While Hugo is a culmination of Scorsese’s knowledge of the industry, it also presented new hurdles for the prodigious director. 3-D cinematography is still in its early days, and brought a new level of challenges to the filmmaker and his crew, in terms of how to navigate the technology. Thanks to Scorsese’s undeterred vision, Hugo garnered multiple Oscar nominations, and he should be commended for making a film that was such new ground for him, yet based on a subject so dear to his heart. Hugo, with its fantastical elements and child-like story, may not appear to be typical Scorsese, but it is the perfect frame for his homage to a much-loved and ever-changing industry. Hold that thought, and I’ll politely ask you to please join me again next week to discover if Hollywood has yielded up another work of substance, or a nonsensical bit of fluff for…Horror News! Toodles!

While Hugo is a culmination of Scorsese’s knowledge of the industry, it also presented new hurdles for the prodigious director. 3-D cinematography is still in its early days, and brought a new level of challenges to the filmmaker and his crew, in terms of how to navigate the technology. Thanks to Scorsese’s undeterred vision, Hugo garnered multiple Oscar nominations, and he should be commended for making a film that was such new ground for him, yet based on a subject so dear to his heart. Hugo, with its fantastical elements and child-like story, may not appear to be typical Scorsese, but it is the perfect frame for his homage to a much-loved and ever-changing industry. Hold that thought, and I’ll politely ask you to please join me again next week to discover if Hollywood has yielded up another work of substance, or a nonsensical bit of fluff for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews