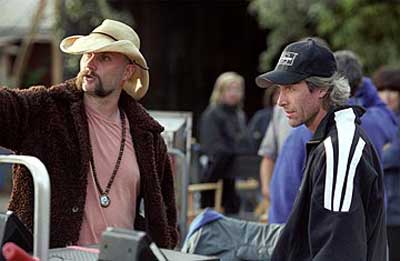

Although he’s only 45, Marcus Nispel has been making TV commercials and music videos for 20 years, as he says, “to pay the bills.” But, obviously, Nispel’s heart has been to make feature films. He burst onto the scene with a revised Texas Chainsaw Massacre, starring Jessica Biel, in 2003. That version of the often-filmed tale in sequels and remakes stood out due to Nispel’s infusion of harsh reality using a washed-out stylized palette of colors and with most of the work created in-camera on set. Now, Nispel is back with another reimagining, this time, with his take on the Friday the 13th series, where he is going back to actually remake the original 1980 film. Like Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Nispel is going to the original root of the material of the first film with Friday the 13th, re-inventing the original myths upon which those legendary horror franchises are based.

Although he’s only 45, Marcus Nispel has been making TV commercials and music videos for 20 years, as he says, “to pay the bills.” But, obviously, Nispel’s heart has been to make feature films. He burst onto the scene with a revised Texas Chainsaw Massacre, starring Jessica Biel, in 2003. That version of the often-filmed tale in sequels and remakes stood out due to Nispel’s infusion of harsh reality using a washed-out stylized palette of colors and with most of the work created in-camera on set. Now, Nispel is back with another reimagining, this time, with his take on the Friday the 13th series, where he is going back to actually remake the original 1980 film. Like Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Nispel is going to the original root of the material of the first film with Friday the 13th, re-inventing the original myths upon which those legendary horror franchises are based.

Why did you decide to take on Friday the 13th, having already remade a horror classic with Texas Chainsaw Massacre?

I think it’s an interesting task to revive the franchises. I enjoy it because watching these types of movies is a ritual. People know what’s going to happen – the different stages. They wouldn’t want it any other way. It’s got a receptive and interested group of fans. You give them what they want but not what they expect. But you can put twists on it. There is a lot to be said for remaking something like it. If you look at the original, that came out after Texas Chainsaw and Halloween. They had spawned that yarn already. It’s a similar type of situation. If it was a crime movie or who-done-it, you wouldn’t want to make it. Here we go back to the original mythology from the first few movies. It’s going back to the root of that.

What specific successes are you taking from your Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake?

There are things you can’t change, but all the rest can be changed – fresh jumps that we come up with. What is the ring that holds it all together? You don’t want to upset the fanboys. In that regard, all remakes are the same. They have a certain value system that you bring along as a director. How far is too far? How little is too little? The story is different.

What is exactly is different with this version of the story?

I read the script and I liked it a lot. It was a page turner like Texas. Everybody liked it. We had been developing it, but no script came in that we liked. Two weeks before the writer’s strike, a script came in that we liked. After two weeks, Michael Bay, the writers and three studios all liked the script. The reason we loved it is there was no development. We couldn’t change it. When it came in, we just loved it and couldn’t screw it up. Usually, with a huge franchise, there would be many rewrites and director changes. It’s rarely like this. If you overwork it, it comes out bad. Better things happen when it’s fresh.

What was your shooting process on the film?

What was your shooting process on the film?

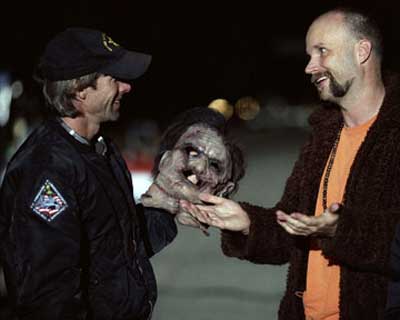

My cinematographer was the DP from the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre [Daniel Pearl]. It was a much more calculated effort. We had as many days and hours as the original. At then end of the day, you have the same type of crew and days to get it done. What you look at as a director is how much time you have to do the damage. Most likely, if you had more time, it wouldn’t be right. I saw the directors’ commentary from John Carpenter. Halloween was redone so many times, and every time that they tried to better it, with more effects and cinematography, [but] that’s exactly where it failed. Most likely, having less is for the better – having to be inventive is much better.

Is there a good deal of gore effects like with Tom Savini in the original Friday the 13th?

We have very little. Every time you put blood on them, they have to do a wardrobe change. You stop doing it. We do it later with CG. At the end, you cut it together, and it’s easier without all of that blood. Without even trying, you end up with something much more sophisticated. We don’t have that much blood in my movies. In the originals, they have less blood than a CSI episode. There’s no gore in the first Texas Chainsaw. It’s a trick.

How did you re-approach the character of Jason?

I broke it up by kills. That’s definitely there. I’d like to believe so. He’s obviously a killer. The writers never refer to Jason this way. They refer to him as the anti-hero. The antagonist is always the asshole who gives everybody trouble in the group of young kids. The monster is a guy who finds our sympathy somehow. I think a lot of the fanboys who like these kind of movies like the killer. Rob Zombie is interested in the kids. Ususally, the killer is wronged in some way by the preppies and yuppies and beauty queens. I always identify with the killer. In Texas, Leatherface’s face was messed up, so these beauty queens who used to heckle him, he takes their pretty faces and wears them as his own face. In Carrie, it’s a revenge movie. Who didn’t go as a geek to prom night feeling ostracized? Jason’s mythology is a kid that was sent to camp and was somewhat off, the camp counselors were supposed to look after him, but the kid drowns when the counselors are f*cking around. And Jason comes back. We are not making a movie-of-the-week, but there’s a reason why these types of characters relate to people in some way. If you just try to come up with the boogeyman, people might not be interested in them. In the first one, where he wasn’t in it, there’s not that much supernatural stuff going on – only in the end where it’s a dream sequence. The monster living and breathing and who could be your neighbor. As exciting as it would be in a sci fi movie, you know that a supernatural CG monster isn’t real.

What were the parameters of the shoot?

Even though we had slightly more money than Texas Chainsaw, we had fewer days – about four weeks. We shot in Texas making it look like New Jersey even though we didn’t have a camp or a lake. We had to figure out how to do that. It was a strange and interesting. The difference between the typical horror movie and this, you don’t have a fly-by-night horror movie. You do wind up with very talented actors. Your duty is to find the next Jamie Lee Curtis or Jessica Biel or Sigourney Weaver. To wind up in a movie of this sort with good actors, you become the type of director who blends into the wall – you make good casting decisions, but let them run and keep things lively. I usually give them three takes max and then we move on so that’s it’s a real experience and nobody gets too comfortable. You want to keep it acute and immediate, and good things come out of that.

Do you generally like use the same crew members from film to film and on this film as well?

Because we wound up back in Austin, a lot of the crew members were the same. They have the same task: almost 40-50 setups per day. For one thing, you have half the days of most movies. You have much less days, so you have to work much faster. I like a lot of detail and choices for the editors. I don’t like a shoot day where people sit around. You want it to be a muscular experience. If I did a movie like The Ring, it would be different. You want to have your angles for the kills. You set up the suspense shots.

How much work did you do with visual effects on the film?

In a movie like this, you don’t want to have too much in it. When I started going to the movies, one of my first big movie experiences was Close Encounters. Nothing looked like digital effects. If it would have looked fake, you would have frowned upon that. Now, there is a whole new generation that grew up with video games. They have a much higher tolerance of digital effects. I think unless you do a cartoonish type of movie like The Spirit and 300, I try to stay away from it. For a suspense movie, where you have to suspend people’s cynicism, you want to make them believe that it is really happening, [and] a digital effect would ruin it. Right away, it would lose its value and authenticity of what it’s trying to be. You deal with fire and dangerous situations, but you don’t want it to read like that. 99% of the scene should be real, but 1% of the moment should be CG. Watching Benjamin Button, 99% of all shots were CG. It’s a real accomplishment, but it’s rare. Plus, you have little money with this type of movie going in. Am I going to spend it on special effects, or am I going to spend it on a great actor? I would like to do a more special effects-based movie. I worked for an optical house, but I never got a chance to use it.

What future movies would you like to make?

I wanted to do 1001 Arabian Nights or The Thief of Baghad. It gets suspicious if you do too many horrors. To do a movie of this sort [Friday the 13th] where people jump out of their seats, it’s a perfect vehicle for that. You want to satisfy yourself on a different level. I’d like to do a thriller next. It all depends on the next script that comes through the door. When I grew up in Germany, movies would come out in America and we would know about them, but for a whole year, we wouldn’t get to see them. We were so hyped by the time the movie came out, we had played the movie in the sandbox and in the treehouse. I’m interested in characters that trigger that, like [in] Conan and Star Wars. Something that really winds up in your DNA. To deal with that type of character would be fun. I get scripts all the time, but the big scripts go to the big directors. To do something decent, it would be winning the lottery to get the super great script. You don’t want to get James Cameron’s leftovers. You always develop something. To develop something from scratch could take years. The great thing with the remakes is that it goes through the system much quicker. Pathfinder was my concept all the way through, but it’s a tough market to compete. You’ve got to come flying out of the gate.

What happened to your movie remake of Frankenstein that was a TV pilot?

Dean Koontz and Martin Scorsese and me. But it was top heavy for a TV show. I’ve never seen anything dark done for TV. You sit in a movie theater and it’s suspenseful. The crinkling of a bag could take you out of a suspenseful movie. On TV, it’s always about urgency and dialogue. That’s the reason. You can have a law show or a sitcom… the moment you try to do suspense, it’s tough to do in that medium.

How does your work go over in Germany?

That’s the country where I seem to sell the least. An R-Rated movie in Germany can only be shown after midnight. The original Texas was declared as illegal. I couldn’t get it on video. In the other European countries, my movies work well.

What do you think is next for you?

Immaculate Conception – it is ostensibly a Rosemary’s Baby – a girl gets pregnant and doesn’t know how. She feels everybody is against her and something is going on. Just when you feel you know where it’s going at the end of the first act, with a demon seed, you realize that it’s a DNA cloned body of Christ. A religious war is being fought over it. It’s more like a thriller or a MarathonMan.

Interview: Marcus Nispel – Director

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews