SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“The oceans during the late nineteenth century are no longer safe, and many ships have been lost. Sailors have returned to port with stories of a vicious narwhal (a giant whale with a long horn) which sinks their ships. A naturalist, Professor Aronnax, his assistant Conseil, and professional whaler Ned Land join a US expedition which attempts to unravel the mystery.” (thanks to IMDB for that elaborate synopsis)

REVIEW:

I had always assumed that the spate of filmed adaptations of Jules Verne novels in the fifties must have been because his books came out of copyright fifty years after his death in 1905: Around The World In Eighty Days (1956), From The Earth To The Moon (1958), Journey To The Centre Of The Earth (1959), Master Of The World (1961), Mysterious Island (1961), Five Weeks In A Balloon (1962). That does not, however, explain the release of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954), a Walt Disney production. It seems at least a month too early. Whatever their motivation, the Disney corporation must have been delighted with the enthusiastic response to the film, which proved once and for all that the way ahead for Disney was in live-action movies, as animated features became more expensive to produce.

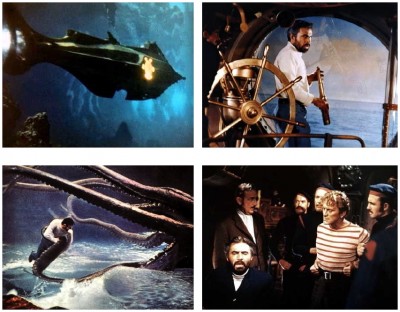

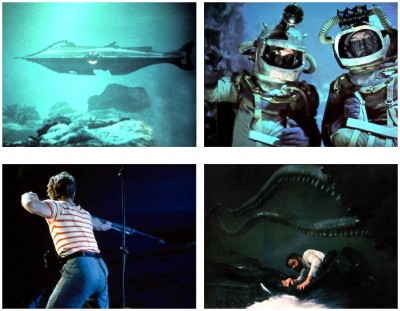

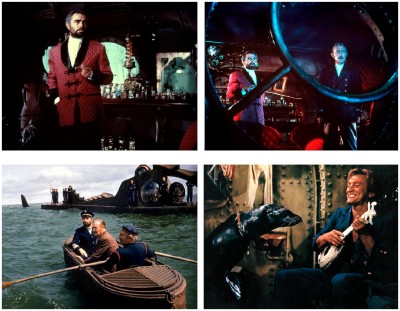

Still considered one of Disney’s most successful non-animated films, 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea may have been a little over-rated, though Richard Fleischer‘s direction is more than adequate, and the set-pieces are well-staged, including the celebrated battle with a giant squid. Also in the film’s favour is a good performance from James Mason as the obsessed Captain Nemo, an anarchist anti-hero alone against the world, who uses his submarine to sink warships – the Nautilus itself is a magnificent piece of Victoriana steam-punk inside and out. On the debit side is the character of harpooner Ned Land, badly scripted and poorly acted as a noisy vulgarian. Because of this, much of the sombre Byronic quality of the original novel is lost, although James Mason’s darkly intelligent performance helps a great deal.

Still considered one of Disney’s most successful non-animated films, 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea may have been a little over-rated, though Richard Fleischer‘s direction is more than adequate, and the set-pieces are well-staged, including the celebrated battle with a giant squid. Also in the film’s favour is a good performance from James Mason as the obsessed Captain Nemo, an anarchist anti-hero alone against the world, who uses his submarine to sink warships – the Nautilus itself is a magnificent piece of Victoriana steam-punk inside and out. On the debit side is the character of harpooner Ned Land, badly scripted and poorly acted as a noisy vulgarian. Because of this, much of the sombre Byronic quality of the original novel is lost, although James Mason’s darkly intelligent performance helps a great deal.

The film’s plot, which has very little to do with Verne’s original, concerns Professor Aronnax (Paul Lukas) and his two companions, Conseil (Peter Lorre) and Ned Land (Kirk Douglas), who board an American warship to take part in a search for a mysterious sea monster that has been plaguing shipping in the area. A large reptilian form with jagged scales and large glowing eyes, the sea monster is sighted and fired upon by the warship, with the result that it turns around and rams the warship with tremendous force. The Professor, Conseil and Ned escape from the sinking ship in a lifeboat and eventually find themselves alongside the sea monster, which turns out to be a man-made vessel. Upon entering the vessel they are greeted by Captain Nemo, a scientist ahead of his time who, with the aid of his underwater ship Nautilus, is conducting a campaign of destruction against weapons manufacturers, by ramming and sinking their ships. Nemo wants to force the nations of the world to abolish war, but at the same time he is seeking revenge on those responsible for the death of his wife and child, both of whom died at the hands of arms dealers attempting to force Nemo to hand over his scientific secrets.

The film’s plot, which has very little to do with Verne’s original, concerns Professor Aronnax (Paul Lukas) and his two companions, Conseil (Peter Lorre) and Ned Land (Kirk Douglas), who board an American warship to take part in a search for a mysterious sea monster that has been plaguing shipping in the area. A large reptilian form with jagged scales and large glowing eyes, the sea monster is sighted and fired upon by the warship, with the result that it turns around and rams the warship with tremendous force. The Professor, Conseil and Ned escape from the sinking ship in a lifeboat and eventually find themselves alongside the sea monster, which turns out to be a man-made vessel. Upon entering the vessel they are greeted by Captain Nemo, a scientist ahead of his time who, with the aid of his underwater ship Nautilus, is conducting a campaign of destruction against weapons manufacturers, by ramming and sinking their ships. Nemo wants to force the nations of the world to abolish war, but at the same time he is seeking revenge on those responsible for the death of his wife and child, both of whom died at the hands of arms dealers attempting to force Nemo to hand over his scientific secrets.

The film ends with Nemo’s suicide as his atomic submarine explodes in a symbolic mushroom cloud. Verne’s submarine was, of course, not nuclear-powered, but the Disney version of the story is the one most people remember. Admittedly, the original novel is quite long and has not dated well, but it’s amusing to know that when the first real-life nuclear submarine was named Nautilus, the US Navy’s homage to Verne was rather inaccurate. Disney himself was fascinated with technology, and it’s possible that the character of Nemo had some special appeal for him. He poured a great deal of money into the project, ensuring not only that the special effects were first class, but also that the film contained a lot of expensive location work and underwater photography. To direct the film he chose my old friend Richard Fleischer, who was then thirty-seven years old and had been directing since 1946, when he made Child Of Divorce (1946) followed by a number of small-budgeted but impressive films, including Trapped (1949), The Armoured Car Robbery (1950) and Arena (1953), which established his reputation as an above-average filmmaker. But Disney’s choice was a strange one, seeing that Fleischer is the son of Max Fleischer, a pioneer animator who was one of Disney’s greatest rivals. It was a paradox that also puzzled Richard Fleischer at the time, or so he told me when I was lucky enough to run into him on the set of Conan The Destroyer (1984).

The film ends with Nemo’s suicide as his atomic submarine explodes in a symbolic mushroom cloud. Verne’s submarine was, of course, not nuclear-powered, but the Disney version of the story is the one most people remember. Admittedly, the original novel is quite long and has not dated well, but it’s amusing to know that when the first real-life nuclear submarine was named Nautilus, the US Navy’s homage to Verne was rather inaccurate. Disney himself was fascinated with technology, and it’s possible that the character of Nemo had some special appeal for him. He poured a great deal of money into the project, ensuring not only that the special effects were first class, but also that the film contained a lot of expensive location work and underwater photography. To direct the film he chose my old friend Richard Fleischer, who was then thirty-seven years old and had been directing since 1946, when he made Child Of Divorce (1946) followed by a number of small-budgeted but impressive films, including Trapped (1949), The Armoured Car Robbery (1950) and Arena (1953), which established his reputation as an above-average filmmaker. But Disney’s choice was a strange one, seeing that Fleischer is the son of Max Fleischer, a pioneer animator who was one of Disney’s greatest rivals. It was a paradox that also puzzled Richard Fleischer at the time, or so he told me when I was lucky enough to run into him on the set of Conan The Destroyer (1984).

“He had called me out of the blue and had asked me to come in and see him. I did so and he presented the project to me, asking ‘What do you think?’ And I said, ‘It looks marvelous and I’d be very interested in working on it, but do you know who I am? More to the point, do you know who my father is?’ And he said, ‘Yes I do.’ I said, ‘Well, I’d love to do the picture but I don’t want to offend my father. He might feel I was betraying him by working for you. I wouldn’t want to take this assignment without his blessings.’ And Walt said, ‘You phone your father tonight and tell him you what you want to do, then phone me tomorrow with the answer.’ So I phoned my father and he said, ‘That’s absolutely fantastic. Your career is your career and you must do that film. Tell Walt that I think he’s got very good taste in choosing you.’ And after that my father and Walt became very good friends after years of animosity. My father, who had retired by then, lived in New York and from then on, whenever Walt went to New York, he would always phone my father and arrange to have lunch with him. It was a marvelous thing to have happened, that these two giants of animation finally buried their differences and became friends.”

“He had called me out of the blue and had asked me to come in and see him. I did so and he presented the project to me, asking ‘What do you think?’ And I said, ‘It looks marvelous and I’d be very interested in working on it, but do you know who I am? More to the point, do you know who my father is?’ And he said, ‘Yes I do.’ I said, ‘Well, I’d love to do the picture but I don’t want to offend my father. He might feel I was betraying him by working for you. I wouldn’t want to take this assignment without his blessings.’ And Walt said, ‘You phone your father tonight and tell him you what you want to do, then phone me tomorrow with the answer.’ So I phoned my father and he said, ‘That’s absolutely fantastic. Your career is your career and you must do that film. Tell Walt that I think he’s got very good taste in choosing you.’ And after that my father and Walt became very good friends after years of animosity. My father, who had retired by then, lived in New York and from then on, whenever Walt went to New York, he would always phone my father and arrange to have lunch with him. It was a marvelous thing to have happened, that these two giants of animation finally buried their differences and became friends.”

“When Walt first asked me to his studio and showed me the material he had so far on 20,000 Leagues, the project hadn’t really got very far. There was no script, there wasn’t even a storyboard, it was just a collection of production ideas and illustrations showing what the submarine would look like and what some of the episodes would be about. But it looked a fascinating subject and I’d always been interested in the book since I was a child. The thing that was most interesting to me, and was the real challenge of the story, was just how to get the wonder of a submarine across to modern-day audiences for whom the submarine was no miracle but a familiar piece of technology. At the start I wasn’t sure whether or not it could be done but, when I saw the sketches and plans, I knew it was a very good and worthwhile project.”

“When Walt first asked me to his studio and showed me the material he had so far on 20,000 Leagues, the project hadn’t really got very far. There was no script, there wasn’t even a storyboard, it was just a collection of production ideas and illustrations showing what the submarine would look like and what some of the episodes would be about. But it looked a fascinating subject and I’d always been interested in the book since I was a child. The thing that was most interesting to me, and was the real challenge of the story, was just how to get the wonder of a submarine across to modern-day audiences for whom the submarine was no miracle but a familiar piece of technology. At the start I wasn’t sure whether or not it could be done but, when I saw the sketches and plans, I knew it was a very good and worthwhile project.”

“I spent a year preparing the film. I worked on the screenplay with the writer Earl Fenton right from the start because, to begin with, there was no actual story. You can’t make a story out of the book because it doesn’t have one. The book really consists of a series of unrelated incidents with a few clues as to what might be a story about Nemo. There were all sorts of allusions as to what he is doing under the sea and why, allusions to what his politics are and what happened to his family and so on. So Earl Fenton and I found it very interesting to try to reconstruct a story from what was hinted at in the Jules Verne original. The odd thing is that now 20,000 Leagues is always thought of in terms of our story, the story of the film, instead of what is in the actual book. Our trick was to retain the basic incidents that people always remembered from the book, but not necessarily in the same order. For instance, everybody remembers the underwater burial and the fight with the squid, so we had to include those two incidents, but our motivations for them were quite different from the book. I must say that it was Earl Fenton who came up with a way of approaching the whole thing. He decided, and I fully agreed, that the only way you could tell this story and make it work as far as suspense was concerned, was to make it a prison/jailbreak story, and that is basically what we did. The three men were captured by Nemo and kept in the submarine, and we treated them as if they were in a prison story – all their time was spent planning an escape, and making several aborted attempts along the way, before finally succeeding at the end.”

“I spent a year preparing the film. I worked on the screenplay with the writer Earl Fenton right from the start because, to begin with, there was no actual story. You can’t make a story out of the book because it doesn’t have one. The book really consists of a series of unrelated incidents with a few clues as to what might be a story about Nemo. There were all sorts of allusions as to what he is doing under the sea and why, allusions to what his politics are and what happened to his family and so on. So Earl Fenton and I found it very interesting to try to reconstruct a story from what was hinted at in the Jules Verne original. The odd thing is that now 20,000 Leagues is always thought of in terms of our story, the story of the film, instead of what is in the actual book. Our trick was to retain the basic incidents that people always remembered from the book, but not necessarily in the same order. For instance, everybody remembers the underwater burial and the fight with the squid, so we had to include those two incidents, but our motivations for them were quite different from the book. I must say that it was Earl Fenton who came up with a way of approaching the whole thing. He decided, and I fully agreed, that the only way you could tell this story and make it work as far as suspense was concerned, was to make it a prison/jailbreak story, and that is basically what we did. The three men were captured by Nemo and kept in the submarine, and we treated them as if they were in a prison story – all their time was spent planning an escape, and making several aborted attempts along the way, before finally succeeding at the end.”

“The Disney special effects and technical people were really fantastic on that film. One of the things they devised was the first real underwater camera. It didn’t exist before that film. The idea of putting a Mitchell underwater was all theirs, it was designed and developed at the studio. We spent ten weeks doing the underwater work in the Bahamas, then we went to Jamaica, where we did the cannibal island sequence, for about a month. Then we came back to the studio and did the rest of the picture inside, which was really the bulk of it. Of all my films I think it’s one of my best efforts, though I haven’t seen it recently. The Disney people re-release it every once in a while, and it had an enormous success in Paris in 1977 – it got great reviews from the French critics. It’s kind of a thrill for me to feel that a film I made thirty years ago is still a successful film for modern audiences.” On that rather upbeat note, I’d like to thank Cinefantastique Magazine volume 14 issue 3 for assisting me in my research for this article, and invite you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the back-streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

“The Disney special effects and technical people were really fantastic on that film. One of the things they devised was the first real underwater camera. It didn’t exist before that film. The idea of putting a Mitchell underwater was all theirs, it was designed and developed at the studio. We spent ten weeks doing the underwater work in the Bahamas, then we went to Jamaica, where we did the cannibal island sequence, for about a month. Then we came back to the studio and did the rest of the picture inside, which was really the bulk of it. Of all my films I think it’s one of my best efforts, though I haven’t seen it recently. The Disney people re-release it every once in a while, and it had an enormous success in Paris in 1977 – it got great reviews from the French critics. It’s kind of a thrill for me to feel that a film I made thirty years ago is still a successful film for modern audiences.” On that rather upbeat note, I’d like to thank Cinefantastique Magazine volume 14 issue 3 for assisting me in my research for this article, and invite you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the back-streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews