SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

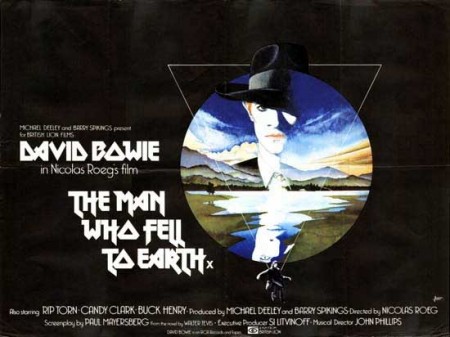

“Thomas Jerome Newton is a humanoid alien who comes to Earth to get water for his dying planet. He starts a high technology company to get the billions of dollars he needs to build a return spacecraft, and meets Mary-Lou, a girl who falls in love with him. He does not count on the greed and ruthlessness of business here on Earth, however.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

By 1975 it had become apparent that a new science fiction film boom was about to start. All the major studios were either making or planning science fiction films. By the beginning of 1976, films that were in various stages of production included The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976), Logan’s Run (1976), Futureworld (1976), The Big Bus (1976), Food Of The Gods (1976), King Kong (1976), Demon Seed (1977), Damnation Alley (1977), Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977) and Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977). But unlike the science fiction boom of the fifties, this one didn’t begin suddenly, nor is it easy to explain its cause. There was no sudden boom in science fiction magazine sales (one of the major reasons for the fifties explosion), rather the opposite. Some of the film companies seem to have decided that science fiction was going to be the next big film trend after the disaster cycle, and so began to buy science fiction properties and put them into production. Noting this, other companies followed suit.

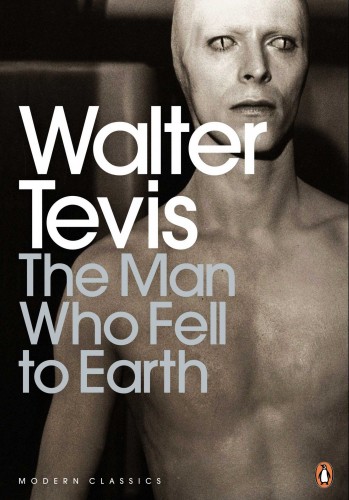

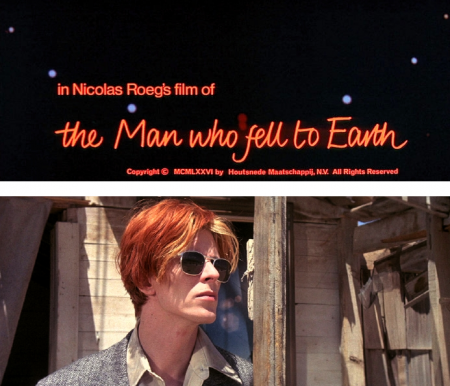

One of the first major science fiction films to be released in 1976 almost stopped the bandwagon in its tracks. Called The Man Who Fell To Earth it was directed by Nicolas Roeg, written by Paul Mayersberg and based on the novel by Walter Tevis. But Tevis’s evocative, almost impressionistic novel about an alien who comes to Earth in order to use the planet’s resources to build a spacecraft large enough to save the inhabitants of his dying world, has been turned into a confused self-indulgent film that alternates between pretentiousness and brilliance. The film is certainly long, pretentious and obscure in places, but the sum total of its images is powerful and, like Solaris (1972), it all makes more sense on a second viewing. The story is disjointed both in space and time because the alien is capable of a kind of psychic time travel – I think – and is eventually corrupted by Earth. His story is strongly reminiscent of the legend of Howard Hughes: The transition from keen young inventor (he patents a number of extraordinary new devices) to ruined recluse, a gin-sodden wreck.

The relatively clear-cut narrative of the novel has been replaced by a non-linear structure that swings back and forth in time in a way that has become Roeg’s trademark as a filmmaker, as with Performance (1970), Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), Eureka (1983) and Insignificance (1985). Elements of the book which were perfectly straightforward (such as the reason for the alien’s visit) have been deliberately obscured. For instance, in the book the alien tries to resist having his head X-rayed because he knows that his ultra-sensitive eyes will be permanently damaged, but in the film the X-rays merely fuse his contact lenses to his eyes. Various unnecessary characters and incidents have been added, including some embarrassing scenes set on the alien’s home planet when his wife and children totter about the sand dunes in what appear to be left-over costumes from an old Buck Rogers serial. There’s also a tedious emphasis on the alien’s sexuality (and every other character’s sexuality too) that wasn’t in the novel and which results in some of the longest, most boring sex scenes ever filmed.

The relatively clear-cut narrative of the novel has been replaced by a non-linear structure that swings back and forth in time in a way that has become Roeg’s trademark as a filmmaker, as with Performance (1970), Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), Eureka (1983) and Insignificance (1985). Elements of the book which were perfectly straightforward (such as the reason for the alien’s visit) have been deliberately obscured. For instance, in the book the alien tries to resist having his head X-rayed because he knows that his ultra-sensitive eyes will be permanently damaged, but in the film the X-rays merely fuse his contact lenses to his eyes. Various unnecessary characters and incidents have been added, including some embarrassing scenes set on the alien’s home planet when his wife and children totter about the sand dunes in what appear to be left-over costumes from an old Buck Rogers serial. There’s also a tedious emphasis on the alien’s sexuality (and every other character’s sexuality too) that wasn’t in the novel and which results in some of the longest, most boring sex scenes ever filmed.

Clearly, like other prestigious filmmakers before him (such as John Boorman), Roeg feels that he can only justify being involved with a science fiction film by making it as pretentious as possible. What he’s trying to say is, “Look, it might appear as if it’s a science fiction film but really it’s very clever.” In effect, he and Mayersberg destroyed all the elements in the book that helped make it good science fiction. I quizzed Paul Mayersberg about this when we met on the set of The Last Samurai (1988). He told me, “When Nicolas Roeg first showed the novel to me, and when we subsequently talked about it, the adaptation looked like a relatively simple matter, at least from the point-of-view of a screenplay. That’s to say there didn’t seem to be any major obstacles in the development of the plot. The characters looked essentially right, the mood was coherent, and so on. Later, as I wrote the first draft, I became aware that the eventual film was not going to be at all easy. Slowly I began to see why the book had not been filmed before. In an odd way it was too much of a good thing. The Man Who Fell To Earth is an extravagant entertainment. It has dozens of scenes that go together, not just in terms of plot, but also like circus acts following one another – the funny, the violent, the frightening, the sad, the horrific, the spectacular, the romantic, and so on. Nic was unwilling to discard any scene, however clumsily written, if he thought it held an element which might be of value, although not perhaps in the form in which it was immediately expressed. The reason was that he believed any thought was worth examining because of what it might lead to. Curiously, I would be inclined to think of the finished film as I wrote, whereas in the early stages of writing, Nic would prefer not to think of the finished film at all.”

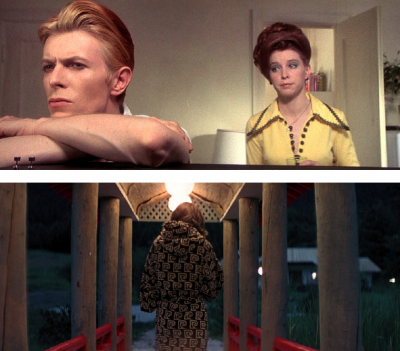

Some of the extraneous ‘circus acts’ are quite impressive, but the film’s main asset is the central performance by David Bowie as the frail, ethereal and vulnerable alien known as Thomas Jerome Newton, whose contact with the harsh world of humanity corrupts and ultimately dooms him. The other members of the cast are fine and dandy too, particularly Candy Clark as Mary-Lou, the crude and boozy girl loving the alien no matter who or what he is. Rip Torn is magnetic as ever in the role of the scientist Nathan Bryce who becomes the Judas who finally betrays Newton, but there are times when it seems that he’s not exactly sure what he’s doing in the film. Rip Torn, of course, continued to intimidate aliens by heading the Men In Black (1997) organisation.

Personally, I like to think of The Man To Fell To Earth as a variation on The Wizard Of Oz (1939). Like another variation, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), it’s about how three people – scientist Nathan Bryce, companion Mary-Lou, lawyer Oliver Farnsworth (Buck Henry) – try to help a stranded alien to return home. But this is an unhappy film, an old-fashioned fairy-tale for those adults who read Jonathan Swift and believe that our world, and those who run it, can be cold, cruel and unfair. The Man Who Fell To Earth lost twenty-three minutes when it was released and many of the so-called ‘circus acts’ were cut, which led one reviewer in Time Magazine to describe it as “Pretty straightforward science fiction.” Before exiting stage left, I must express my extreme thanks to Sight And Sound Magazine Autumn 1975 for assisting me in my research for this article, and then politely ask you to please join me next week to have your innocence violated beyond description while I force you to submit to the horrors of…Horror News! Toodles!

Personally, I like to think of The Man To Fell To Earth as a variation on The Wizard Of Oz (1939). Like another variation, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), it’s about how three people – scientist Nathan Bryce, companion Mary-Lou, lawyer Oliver Farnsworth (Buck Henry) – try to help a stranded alien to return home. But this is an unhappy film, an old-fashioned fairy-tale for those adults who read Jonathan Swift and believe that our world, and those who run it, can be cold, cruel and unfair. The Man Who Fell To Earth lost twenty-three minutes when it was released and many of the so-called ‘circus acts’ were cut, which led one reviewer in Time Magazine to describe it as “Pretty straightforward science fiction.” Before exiting stage left, I must express my extreme thanks to Sight And Sound Magazine Autumn 1975 for assisting me in my research for this article, and then politely ask you to please join me next week to have your innocence violated beyond description while I force you to submit to the horrors of…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews