Writing about Ray Bradbury is a little like writing about the ocean – the entity is so vast you hardly know where to begin. Consider there are six billion humans on this planet, yet there is only one man, one name, that readers associate emotionally with one of the great explorations into the unknown. Back in 1987 a syndicated newspaper cartoon depicted a bleak landscape of Mars as we’ve come to know it close up, thanks to the Viking rocket. The scene was desolate except for one feature standing sharp and clear: A mailbox on which the name ‘Ray Bradbury’ was written. More than six decades after his first published story, genre fans still argue as to the merits of Mr. Bradbury’s work. Science fiction stalwarts have complained that Mr. Bradbury was wary of science and hardware. Others have faulted him for an overbearing sentimentality, a nostalgic longing for a mythical mid-west that makes Norman Rockwell seem like an inner-city documentarian.

“People who talk about Bradbury’s imagination miss the point,” my old friend Damon Knight told me back in 1956. “His imagination is mediocre, he borrows nearly all his background and props, and distorts them badly.” But Mr. Knight was also quick to credit Mr. Bradbury’s penchant for writing about the things that are really important to us, not the things we pretend we are interested in. Another old friend of mine, British author Kingsley Amis, noted Mr. Bradbury’s tendency to fall into that particular kind of sub-whimsical, would-be poetical badness that goes straight to the corny old heart of the Saturday Evening Post. Yet Mr. Amis would also concede that despite Mr. Bradbury’s tendency to dime-a-dozen sensitivity, he is a good writer, wider in range than any of his contemporaries or colleagues.

“People who talk about Bradbury’s imagination miss the point,” my old friend Damon Knight told me back in 1956. “His imagination is mediocre, he borrows nearly all his background and props, and distorts them badly.” But Mr. Knight was also quick to credit Mr. Bradbury’s penchant for writing about the things that are really important to us, not the things we pretend we are interested in. Another old friend of mine, British author Kingsley Amis, noted Mr. Bradbury’s tendency to fall into that particular kind of sub-whimsical, would-be poetical badness that goes straight to the corny old heart of the Saturday Evening Post. Yet Mr. Amis would also concede that despite Mr. Bradbury’s tendency to dime-a-dozen sensitivity, he is a good writer, wider in range than any of his contemporaries or colleagues.

Mr. Bradbury was always more of a fantasist than a science fiction writer – someone more at home in, say, Weird Tales magazine than in Amazing Stories. in fact, Astounding Science Fiction magazine editor John W. Campbell refused to publish Mr. Bradbury at all. But when Christopher Isherwood sang his praises, the post-war slicks snatched up his writing, yanking him from the fierce clutches of the science fiction ghetto, and transforming him into the genre’s first internationally-recognised brand name. During the fifties and sixties, Mr. Bradbury was to science fiction what Stephen King would be to horror during the eighties and nineties – the one recognisable name to those who might know nothing else about the genre.

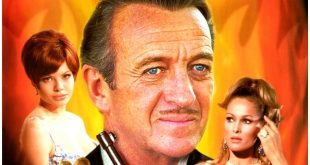

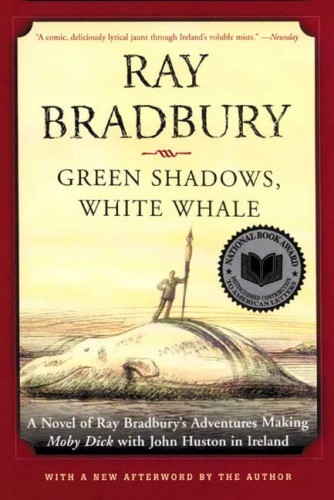

Less is known about Mr. Bradbury’s forays through the dark and deadly voids of Hollywood. Green Shadows, White Whale (published 1992 by Alfred A. Knopf) is an account of Mr. Bradbury’s journey to Ireland to write a screen adaptation of the novel Moby Dick (1956) with director John Huston. I had become a casual member of Mr. Huston’s ‘entourage’ after we met on the set of Beat The Devil (1953), when Mr. Huston had requested Mr. Bradbury’s collaboration on his next big project. Alas, while they made movie magic together, they also made each other profoundly crazy. Mr. Bradbury told me he wrote Green Shadows, White Whale after reading actress Katherine Hepburn’s account of filming The African Queen (1951) with Mr. Huston in Africa. The title itself is a play on Peter Viertel’s novel and film White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), which is also about Mr. Huston.

Less is known about Mr. Bradbury’s forays through the dark and deadly voids of Hollywood. Green Shadows, White Whale (published 1992 by Alfred A. Knopf) is an account of Mr. Bradbury’s journey to Ireland to write a screen adaptation of the novel Moby Dick (1956) with director John Huston. I had become a casual member of Mr. Huston’s ‘entourage’ after we met on the set of Beat The Devil (1953), when Mr. Huston had requested Mr. Bradbury’s collaboration on his next big project. Alas, while they made movie magic together, they also made each other profoundly crazy. Mr. Bradbury told me he wrote Green Shadows, White Whale after reading actress Katherine Hepburn’s account of filming The African Queen (1951) with Mr. Huston in Africa. The title itself is a play on Peter Viertel’s novel and film White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), which is also about Mr. Huston.

On the surface, both men were highly creative – geniuses, in fact – and that’s where the resemblance ends. Mr. Huston was the ultimate in charm and worldly sophistication, and he had a devastating intellect. The only trouble was, although he probed like Plato, he was keener to fasten onto some failure of his fellow man. Mr. Bradbury, like a gullible child, fell into this very complex and perverse intelligence. Mr. Huston later told me that Mr. Bradbury was the most suggestible person he had ever met. For instance, they’d be sitting under a tree and Mr. Huston, who was a brilliant actor, would bite his lip and look worried. Mr. Bradbury would say “What’s the matter, John?” and Mr. Huston would say “That branch doesn’t look safe to me.” So Mr. Bradbury would move. Of course, this was so tempting that Mr. Huston had fun with the ceiling, the walls, the lights – and Mr. Bradbury never did catch on.

On the surface, both men were highly creative – geniuses, in fact – and that’s where the resemblance ends. Mr. Huston was the ultimate in charm and worldly sophistication, and he had a devastating intellect. The only trouble was, although he probed like Plato, he was keener to fasten onto some failure of his fellow man. Mr. Bradbury, like a gullible child, fell into this very complex and perverse intelligence. Mr. Huston later told me that Mr. Bradbury was the most suggestible person he had ever met. For instance, they’d be sitting under a tree and Mr. Huston, who was a brilliant actor, would bite his lip and look worried. Mr. Bradbury would say “What’s the matter, John?” and Mr. Huston would say “That branch doesn’t look safe to me.” So Mr. Bradbury would move. Of course, this was so tempting that Mr. Huston had fun with the ceiling, the walls, the lights – and Mr. Bradbury never did catch on.

There was also the drive to Dublin. Mr. Huston had this conspiracy with his chauffeur. They’d be doing fifty miles an hour, and Mr. Huston would say “What are you doing, Eddie? You’re driving too fast.” Eddie would slow down to thirty miles an hour. After a few moments, Mr. Huston would say “Eddie, didn’t you hear what I said? You’re going too fast!” By this time, Mr. Bradbury was agitated and would agree, “Yes, you’re going too fast, Eddie!” He was doing about ten miles an hour. “You’re still speeding!” Mr. Bradbury would shriek – he seemed on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

There was also the drive to Dublin. Mr. Huston had this conspiracy with his chauffeur. They’d be doing fifty miles an hour, and Mr. Huston would say “What are you doing, Eddie? You’re driving too fast.” Eddie would slow down to thirty miles an hour. After a few moments, Mr. Huston would say “Eddie, didn’t you hear what I said? You’re going too fast!” By this time, Mr. Bradbury was agitated and would agree, “Yes, you’re going too fast, Eddie!” He was doing about ten miles an hour. “You’re still speeding!” Mr. Bradbury would shriek – he seemed on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

While he was torturing others, Mr. Huston was also torturing himself, The trouble was that he couldn’t stop. He was as incapable of changing his behaviour as Mr. Bradbury was in becoming sophisticated by Mr. Huston’s terms. This, of course, is also the secret of Mr. Bradbury’s great genius, of why he is able to transport his readers to so many alien worlds. But if ever there were a mismatched pair for a trip to Mars, Ray and John are them. And I, for one, would very much like to see who got off the spaceship on its return.

While he was torturing others, Mr. Huston was also torturing himself, The trouble was that he couldn’t stop. He was as incapable of changing his behaviour as Mr. Bradbury was in becoming sophisticated by Mr. Huston’s terms. This, of course, is also the secret of Mr. Bradbury’s great genius, of why he is able to transport his readers to so many alien worlds. But if ever there were a mismatched pair for a trip to Mars, Ray and John are them. And I, for one, would very much like to see who got off the spaceship on its return.

Acclaimed actor Rod Steiger, star of the film adaptation of The Illustrated Man (1969), has fonder recollections of his association with Mr. Bradbury. He once told me it was actually he who wrote the last scene of The Illustrated Man: “There was no last scene. Ray was so naive, he was so lost. He’s like a baby Christ – he forgives everyone. So I wrote it in about an hour and a half, and it actually worked. I call him the nicest alien that’s alive. He’s a miraculous angel. He’ll never grow up, and I hope to Christ he never does.” And it’s with that lovely thought in mind I’ll take my leave, until I return next week to sterilise you with fear during another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Acclaimed actor Rod Steiger, star of the film adaptation of The Illustrated Man (1969), has fonder recollections of his association with Mr. Bradbury. He once told me it was actually he who wrote the last scene of The Illustrated Man: “There was no last scene. Ray was so naive, he was so lost. He’s like a baby Christ – he forgives everyone. So I wrote it in about an hour and a half, and it actually worked. I call him the nicest alien that’s alive. He’s a miraculous angel. He’ll never grow up, and I hope to Christ he never does.” And it’s with that lovely thought in mind I’ll take my leave, until I return next week to sterilise you with fear during another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Green Shadows, White Whale – Author Ray Bradbury

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews