SYNOPSIS:

The breakup of the body that this drug causes, helped me to symbolize a breakup too visually Interior unstoppable.

REVIEW:

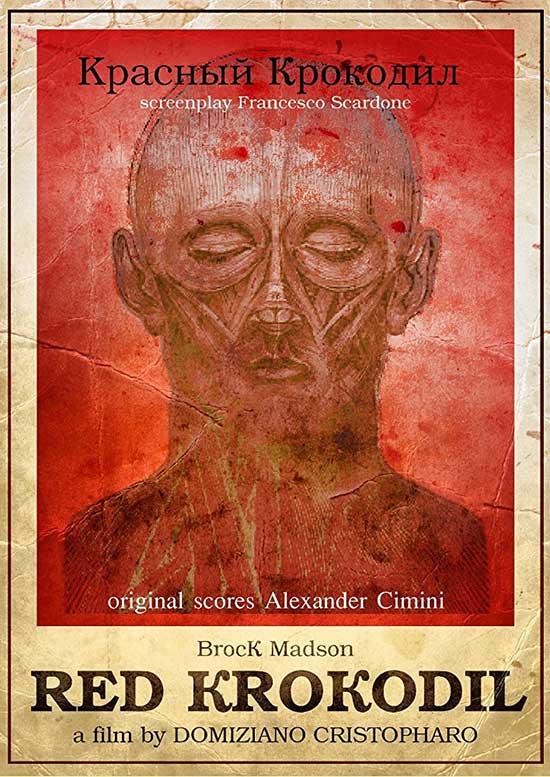

Domiziano Cristopharo is an Italian filmmaker who has played a variety of roles over the years – writer, director, editor, producer, cinematographer, and there’s even a little bit of special effects makeup work on his resume. His films tend to deal with dark and sometimes taboo subject matter, and often feature a variety of beautiful women in various stages of undress as well as a veritable bloodbath as a direct result of his characters (some of them the aforementioned women) being killed in violent and twisted ways. Red Krokodil, then, stands out as a bit of a departure for Cristopharo, as there is no sadistic killer chopping their way through the cast (at least literally, anyway) and no women, beautiful or otherwise, to be found. However, when it comes to the dark subject matter, this film is steeped in it.

Cristopharo’s (director of House of Flesh Mannequins and Bloody Sin, producer of American Guinea Pig: Sacrifice and the John Wayne Gacy-inspired Torment) film first appeared at the Samain du Cinema Fantastique film festival in France back in 2012, but just last month (January, 2018) was re-released as a director’s cut by Unearthed Films. Directed by Cristopharo and written by Francesco Scardone, Red Krokodil is ultimately a film depicting the horrors of drug use, focusing solely on “Him” (played by Brock Madson in what appears to be his acting debut), a man addicted to desomorphine, aka krokodil. Desomorphine is an opioid, around since the 1930s – a faster and more powerful pain killer than morphine – but taken off the market in the early 1980s.

Today, desomorphine is being made at home using ingredients like paint thinner and hydrochloric acid, and much like meth, it’s quickly burning its way through its users. Its users are essentially eaten away from the inside, often losing limbs and succumbing fairly rapidly. Among other names (“flesh-eating drug” and “the zombie drug”), it’s called krokodil because the skin around the injection site slowly dies and becomes green and scaly.

Throughout Red Krokodil, “Him” paces his small, dirty, sparsely-furnished apartment, alternately cooking up new drugs and spinning out of control thanks to the high and subsequent withdrawal of said drugs, and all against a post-Chernobyl wasteland backdrop. We, the audience, see the life of the user as it is: at times, it is euphoric, and our protagonist runs nude through the fields of his dreams or tries to communicate with the reflections of light dancing across his wall. Other times, it isn’t so pretty, as the dope sick “Him” writhes in sweaty pain, inspects the rotting flesh under the bandages covering his track marks, and has paranoid hallucinations of others there with him, whether in the form of a bunny man standing over him, or a mutant-like monster behind a door, or even the eye of god peering though a hole in his wall. Much like the narrative of Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Red Krokodil ebbs and flows right along with the man’s drug usage, bringing us up and down with him.

The way Cristopharo shows the self-inflicted destruction of “Him” from both points of view, an “outer” that the audience witnesses and an “inner” that is witnessed/imagined through his senses, is both artistic and upsetting. While he sometimes sees himself as clean, strong, muscular, we see him as he really is: hair falling out, missing teeth, sores mapping out his past highs. Through a limited voiceover monologue, we know that, at times of clarity, “Him” knows he needs help, knows he hasn’t always been like this and needs to find a way out. But just as quickly, he is shooting up again, to kill the pain, or the voices, or the nightmares, or the reality. Knowing what we know about the effects of this drug, we never assume there will be a happy ending, but rather find ourselves dreading just how bad it will all get before an escape is found. Thankfully, the finale is one of the high points of the film, a bittersweet sequence that, once complete, seems like the only possible way this story could truly end.

Red Krokodil is a dark, brooding, depressing film that moves at a slow but purposeful pace. It is visually fascinating, with a certain beauty brought to the ugliness of the story, a credit to the cinematography skills of the director (of special note, a simple scene of a centipede on a wall in the bathroom ends up mesmerizing). Madson’s portrayal of the addict is dead-on, never going over the top but still selling the depravity of his situation, an impressive feat as this is for the most part a one-man show. The film is one part physical decay (think Thanatomorphose or Contracted), one part mental decline, and ten parts debilitating, irrational addiction that almost makes Requiem for a Dream look hopeful in comparison. It is upsetting, it is depressing, it is borderline nihilistic, and it is a masterful accomplishment.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews