SYNOPSIS:

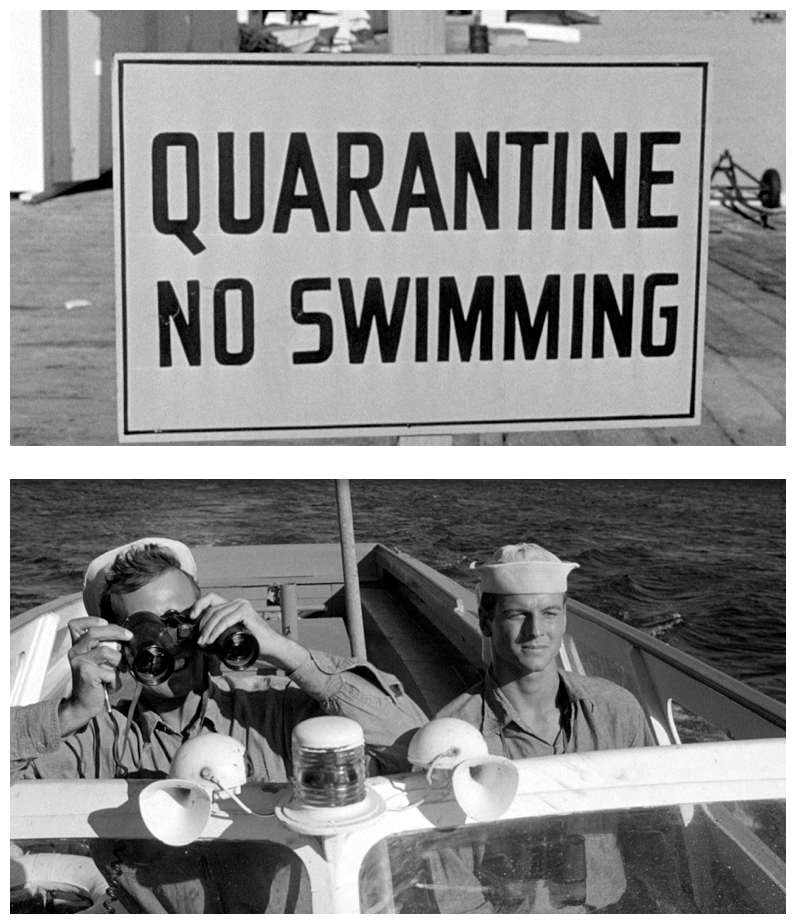

“An earthquake unleashes a giant mollusk in California’s Salton Sea. The site is near a military base and the first victim is a navy skydiver testing parachutes and the two sailors sent to collect him from the water. Soon Naval Investigator Lt. Commander John ‘Twill’ Twillinger is on the case. They find the sailors’ boat which is covered with a white goo. Soon Navy divers are looking for the missing men and recover a large round sac which they recover and sent the base lab. One of the divers is killed in an encounter with the creature and they think the crisis is over. They don’t realise that the sac they transported to the lab is in fact the creature’s egg and another mollusk hatches, this time on the base.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

1957 was a productive year in the history of science fiction monster movies. The Arctic gave birth to The Deadly Mantis (1957). Italy was terrorised by an overgrown Venusian reptile in Twenty Million Miles To Earth (1957). Chicago was overrun by giant grasshoppers in The Beginning Of The End (1957). California was plagued by a cubist nightmare from outer space in Kronos (1957), and a team of scientists on a remote pacific island suffered an Attack Of The Crab Monsters (1957). But the most popular locale for oversized creatures was the desert surrounding the US/Mexican border where the beleaguered citizenry was beset by The Cyclops (1957), The Black Scorpion (1957), The Monolith Monsters (1957) and The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), all within a span of a few months. One of the few films to show more than an average amount of skill and imagination during this epidemic of low budget science fiction was The Monster That Challenged The World (1957).

Although it relied upon many of the traditional elements featured in other genre movies (radioactivity, giant creature, south-west USA, etc.), The Monster That Challenged The World still managed to generate an above-average degree of suspense and believability while maintaining the all-important ‘sense-of-wonder’ in the eye of its beholders. The Monster That Challenged The World was produced by Arthur Gardner and Jules Levy, and directed by Arnold Laven. These three men met while in the army during World War Two and, after each had individually pursued his own film career for a few years, they decided to join forces, pool their resources and make movies by incorporating their talents. Working with limited budgets, they made three moderately successful crime thrillers: Without Warning (1952); Vice Squad (1953); and Down Three Dark Streets (1954). United Artists, the distributor for all three films, was pleased with the financial returns and decided to back the next movie produced by the team.

At first the trio didn’t have one particular property they wanted to film, but soon their ideas began to solidify. Laven: “We had several projects in mind, but those projects did not include The Monster That Challenged The World. They were very nebulous and we wanted to get into business quickly, so we met one day and talked about putting our heads together in order to make a more attractive, more sophisticated science fiction film, a science fiction film with Hitchcockian elements of suspense, reality in the storyline, and which put the actors in a position where they could express themselves more as human beings caught in a dilemma than was true with the average science fiction films being made at the time. With that in mind, we started to knock around some ideas.” Based on an outline by David Duncan, the script was eventually realised by a young woman by the name of Pat Fielder who was working for Levy-Gardner-Laven as their secretary at the time.

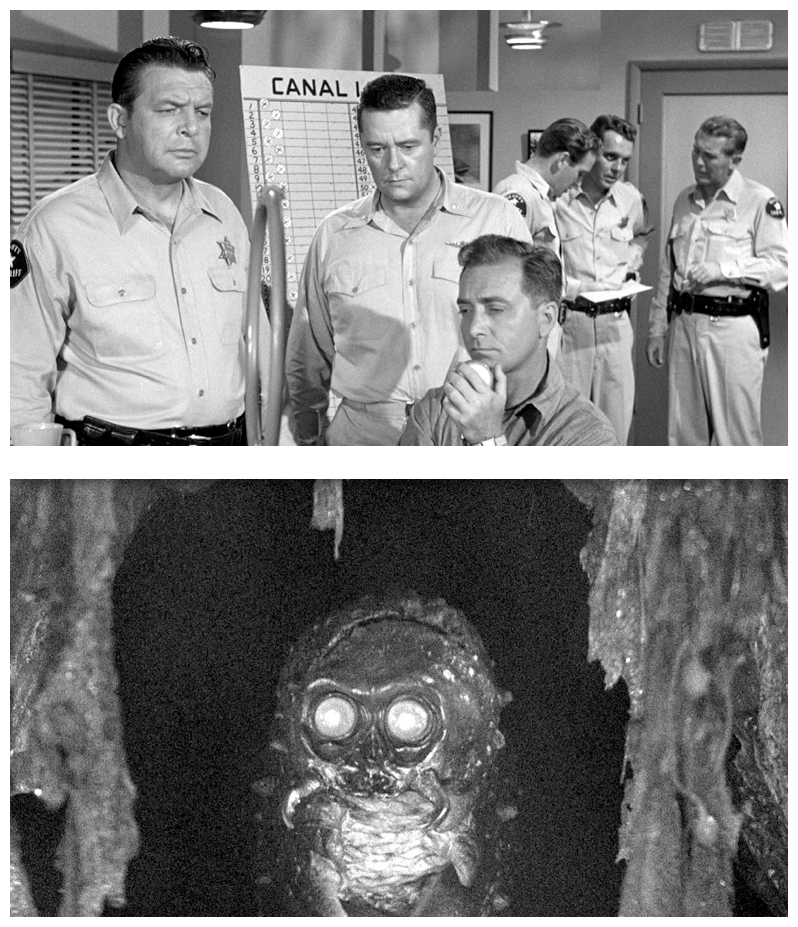

“We knew Pat was a talented girl. Not only was she a marvellous secretary but she had also previously succeeded in publishing material she had written for children. She had a talent for writing and she was also interested in motion pictures, although she had never written a screenplay. Consequently she took on the assignment and eventually came up with a science fiction story which was originally called The Kraken. Somewhere along the line Pat had discovered a piece of literature that related to a prehistoric monster which might still have germs of its existence living in the desert sands. From this she developed the plot outline that ultimately became The Monster That Challenged The World.” Fielder thoroughly researched the subject, consulting all the appropriate scientific sources in an attempt to make the monster as believable as possible, and even contacted the Pentagon to map out how the armed forces would react to such a threat as was posed in her screenplay. She discovered that the Navy would be the branch of service responsible for grappling with such a situation.

Consequently, the Twillinger character was changed from Army to Naval officer. Once the screenplay was complete, Levy-Gardner-Laven then had to find a way to produce the story with the best talent possible within their limited budget. The Monster That Challenged The World was made for a little under US$250,000, shot in eighteen days of first-unit shooting and an additional three days to obtain background footage. “We called every guild and every union, plus all of our friends, to find out who might be available during the brief time we had to make our film. Then we tried to contact the finest technicians hoping we might catch them during a period when they were not involved with other projects and would be available to us.” This resourceful method of putting together a production was highly successful. Respected composer Heinz Roemheld, a friend of Jules Levy from his assistant-director days, had an open period in his schedule and was able to supply The Monster That Challenged The World with one of the most haunting and unusual scores of fifties science fiction.

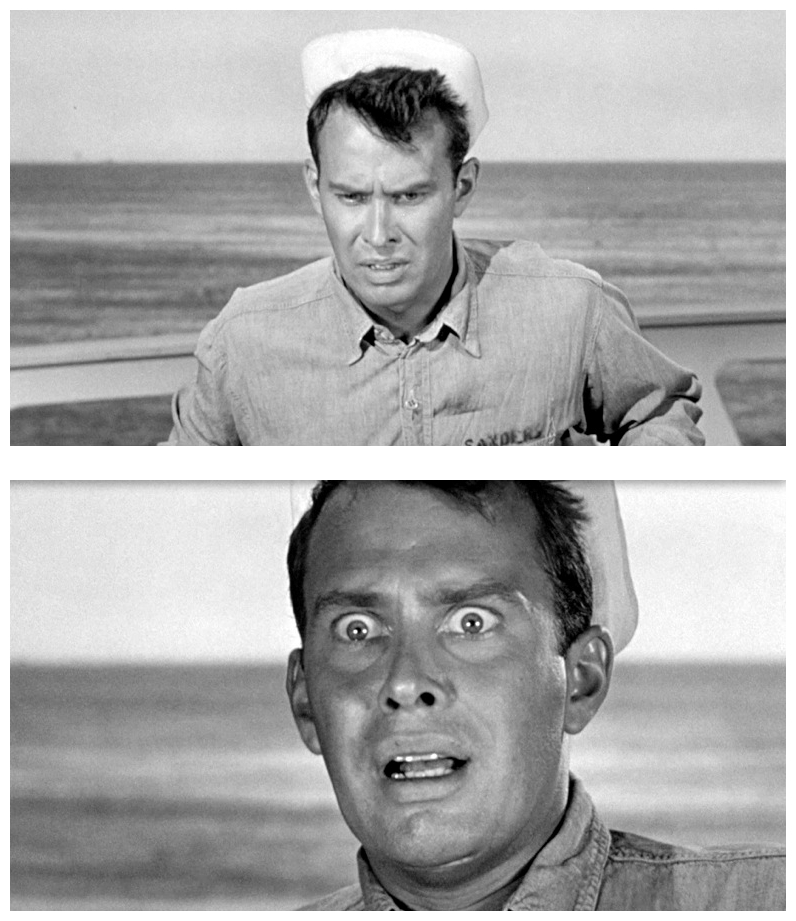

Popular cowboy actor Tim Holt, who had also appeared in such distinguished films as The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre (1948), was in semi-retirement when he was offered the role of Twillinger. The producers got him interested in the screenplay and were able to lure him away from the ranch he was managing in Kansas. For the crucial underwater during the scuba-diving investigation scenes, the producers were able to get Scotty Wellborn, a first rate underwater cinematographer who had begun his career as a glamour portrait photographer at Warner Brothers where Laven had worked as a script supervisor. Assisting Wellborn on the underwater sequences was stuntman Paul Staeder. Laven was forced to rely on the considerable skill of these two men much of the time due to an inner-ear problem which prevented him from doing any deep diving himself. Perhaps the single most important technician recruited for this production was special effects artist Augie Lohman, who was hired to create the mechanical mock-up of the monster. Lohman’s experience in special effects was particularly suited to the task of devising the giant Kraken, as he had recently designed the great white whale for John Huston’s version of Moby Dick (1956).

Through his own research and technical know-how, Lohman and his team were able to produce a sea-beast that was both fearsome-looking and authentically mobile. “If you took the skin off the monster, what you would see is basically a large moulded shell, a giant snail shell, that I remember stood some four or five feet from top to bottom. It was just a huge replica of a snail’s shell built of a lightweight fibreglass material. Fitted into it and then stretched up to a height of eleven or twelve feet was what looked like a giant series of tubes and, if you will, erector-set pieces of metal that were designed so that they could move both laterally and vertically through hydraulic and electric machinery. It was really a marvellous device, a beautifully conceived piece of machinery which could not have existed without Augie Lohman’s unique personal experience as a special effects man. It took three-to-five men to work the rheostats and other controls that would move the monster either up or down, or frontwards or backwards, or give it a rolling forward movement.”

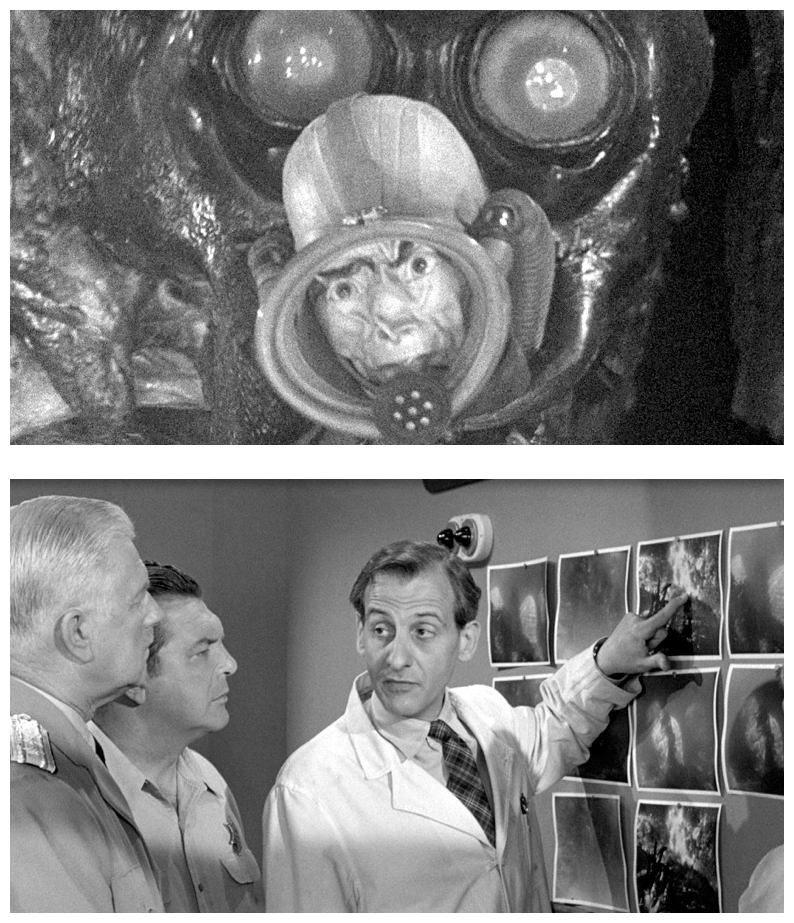

The first full view of the monster is particularly effective. Twillinger (Tim Holt) and Doctor Rogers (Hans Conreid) are in a boat on the Salton Sea when the Kraken suddenly springs up out of the water to one side. The footage of the creature was filmed first and was then rear-projected behind the actors in the boat when the final scene was shot. This dramatic entrance of the monster is not unlike the appearance some twenty years later of the marauding shark in Steven Spielberg‘s Jaws (1975). In a film that required the manipulation of a complex animatronic beast as well as shooting difficult underwater sequences, one might expect that there would have been many irritating snags in the production, but no. “It was a pleasure to make. We had spent a great deal of time making sure that production problems which might occur were anticipated before we started.” By hiring the best available talent and planning well ahead of the shooting schedule, the makers of The Monster That Challenged The World were able to bring in their film on a small budget without any problems, a skill which seems to have eluded many big-budget filmmakers since then.

The end result is a tidy little thriller that features all the usual elements common to genre films of the fifties: a square-jawed hero determined to get to the bottom of all the trouble; a stern scientist who provides the rationale for the beastliness; and the comely love interest who provides the female side of the equation. The Monster That Challenged The World succeeds in delivering a couple of genuinely frightening experiences, due to a thoughtful script and filmmakers who treat the material with respect. The film is peopled with understated performances, particularly those of Hans Conreid in a rare dramatic role and ex-cowboy Tim Holt. The monster of the title may not be as menacing as, say, Alien (1979), but it provides enough creepy moments to satisfy all but the most jaded film goers. Nice photography and crisp editing add to the overall effect. Made sixty years ago, it remains a fresh and satisfying example of the genre.

Even with top-notch technical assistance, the ultimate success of the film rests on the validity of the story. From the start, Levy-Gardner-Laven devoted themselves to developing a convincing script, and then continued to inject intelligent substance into the story when on the shooting stage. “We tried to make the best film possible. Also, we were careful not to condescend to the audience, but attempted only to give them the best of everything we had. I assumed that whoever goes to to a science fiction film is both discriminating on one hand, and willing to overlook less sophisticated elements on the other hand. Above all I wanted to appeal to their best taste and judgement.” And it’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me again next week, but not before thanking Al Taylor and David Everitt for assisting in my research for this article. See you in seven days when I have another opportunity to give your cinematic sensibilities a damn good thrashing with the ugly stick for…Horror News! Toodles!

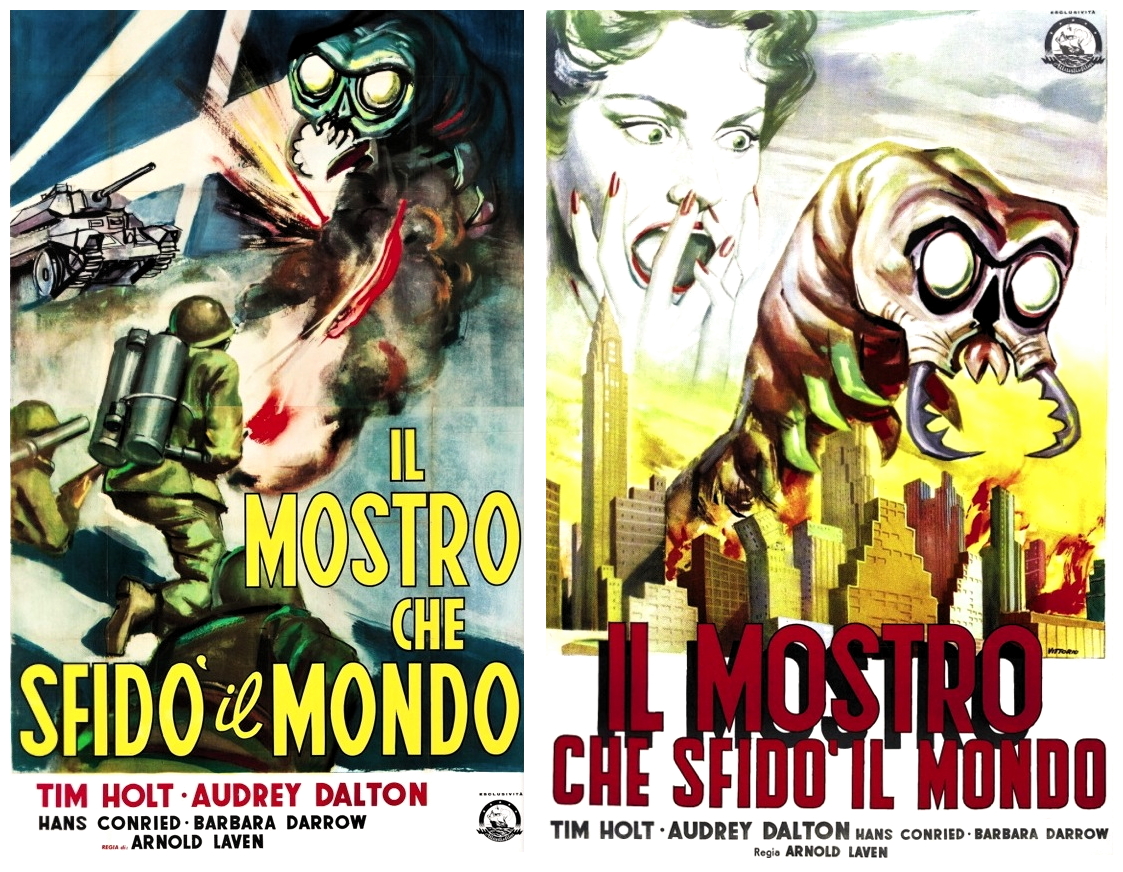

The Monster That Challenged The World (1957)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews