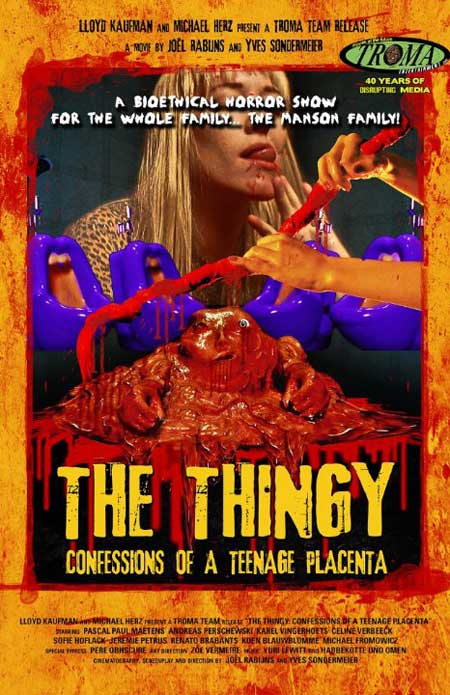

SYNOPSIS:

It’s the placenta coming of age story the world’s been waiting for. As Luke the Placenta enters his teenage years, he tries desperately to connect with those around him, only to be met with indifference, confusion, and cruelty. And the sweet taste of oral fixation.

REVIEW:

Love, like all intangibles, is an enigma. The only way it can be identified is by its surroundings, by its effect, by results, by what it is not, and whether it’s worth it. It’s different things to different people. And, for most of those people, it’s an abstraction, an enigma, even though they feel it, they see its results, but they still can’t pinpoint it. It’s like a subatomic particle which can either be observed or located in space, but not both at the same time. This intangibility leads to a problem, namely: love can create the greatest of freedoms or the greatest of no-exit traps.

The Thingy (original title: The Miracle of Life) is all about the feverish traps. A mother’s overwrought love for her child; a child’s clinging love for his mother; a person’s single-minded devotion to physical perfection; a wife’s dogmatic protection of her deceased husband’s memory; a teenager’s burning desire for acceptance; a trainer’s autocratic obsession with competitive success; a priest’s affected love of God; a teenager’s choked lust for sex; and the same priest’s compulsive lust for Luke the Placenta. Love, desire, lust, obsession; they all stem from the same DNA source, the same need to belong, the same need to be a part of something, to connect with something while not knowing how to do it, while not knowing what that something is, while fumbling about in the dark, groping for something solid to hold close, something to absorb into yourself and with which to become one.

This uncertainty is made clear early on in the film when Marianne (Pascal Maetens), Luke’s mother, takes the newborn to Father Julio (Karel Vingerhoets) to be baptized. She slurs her words; she mumbles under her breath, and finds difficulty articulating what she feels, being fully aware of the absurdity of the situation, as any mother with a particularly odd child would be; yet pushed forward by her dual enigmatic love for God and her child, she presses it and finally blurts out with only slight conviction that Luke (operated by Zoë Vermeire) needs to be baptized.

Love, disguised as lust, is brought to the fore midway through the film, as Luke straddles the alter in church, attempting to make sense of his hunger for Rihanna (Sofie Hoflack), the hottest girl in school; Father Julio, hungry for details, tells Luke to describe her legs; Luke ignores this and continues to pine over Rihanna; Father Julio persists and, again, hungrily insists Luke describe her legs; Luke, absorbed in his own ravenousness for Rihanna, remains oblivious to the priest’s edacity; Father Julio finally backs off of his proclivity for finger-lickin’ luscious legginess but still wants details, the more intimate the better. Soon, the scene spirals into a maelstrom of what can only be described as the priest’s spirited, giddy tickle-molestation of Luke.

The film is made up almost entirely of such scenes, scenes of lust, love, addiction, consummation (as in eating), obsession, desire, fear and hate derived from not being accepted, not being loved and not knowing what love is. Marianne’s maniacal, yet oddly humorous, preoccupation with having a monstrously over-developed right arm is a continuous example of addiction (read: misdirected love) running through the film until it reaches its not-so humorous conclusion. Despite such absurd humor saturating the film, there are black, gaping holes present in every character, holes that the characters instinctively know are there but which they don’t know how to fill without, either literally or metaphorically, consuming, or being consumed by, that which they long for.

Although it’s obviously meant to dredge up silly, scatological memories of the VHS revival of 42nd Street grindhouse twaddle (which, don’t get me wrong, I can be a fan of), Yves Sondermeier and Joël Rabijns, predominant creators of the film, show their serious hand through the black subtext prevalent in the script (but rarely prevalent on 42nd Street) and the highly disturbing last fourteen minutes of the story.

Their technical competence gives them away, as well; the cinematography is lively and eclectic, with plenty of tilts for obliqueness, hand-held shots for tension, low angles to enhance uncertainty, high angle shots of Luke in order to diminish his significance, and the use of a tilt-focus lens for blurry-edged, deep-focused shots in order to create a sense of the unreal. As directors, they’re able to pull out the appropriate over-the-top performances needed from the actors while keeping the portrayals consistent within the context of the story. They do a nice job of blocking-out scenes in tight quarters, notably during the apartment landing segments with the two homeless men, once again using a hand-held camera for jiggly urgency and sharp edits for tension, creating a feeling that the world is closing in on Marianne and Luke.

The music, for the most part, is little more than a low hum, but none the less effective in its molar-grinding malevolence. The special effects are clunky and obvious, but this is to be expected from a film that’s trying to draw out campy laughs from the audience and pay respectable homage to the godfather of neo-grindhouse, Frank Henenlotter.

So, the question still remains: what are we talking about when we talk about love? Raymond Carver would probably say doubt, elusion, a dissembling. The two makers of this film, Yves and Joël, are a bit more visceral and would probably add insecurity, consumption, overindulgence, and digestion to that. After all, near the end of the film, during Luke’s final confession, Father Julio tells Luke “lovers eat each other, you know”, which makes one feel a bit dirty for some reason. But, then, Father Julio also tells Luke, perhaps rightly, that “feeling dirty is a way of repenting”. Something wisely kept in mind after watching any exploitation movie.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews