SYNOPSIS:

“In Africa, girl Jill Young trades a baby gorilla with two natives and raises the animal. Twelve years later, the talkative and persuasive promoter Max O’Hara organises a safari to Africa with the Oklahoma cowboy Gregg to bring attractions to his new nightclub in Hollywood. They capture several lions and out of blue, they see a huge gorilla nearby their camping and they try to capture the animal. However, the teenager Jill Young stops the men that intended to kill her gorilla. Max seduces Jill with a fancy life in Hollywood and she signs a contract with him where the gorilla Joseph ‘Joe’ Young would be the lead attraction. Soon she realises that her dream is a nightmare to Joe and she asks Max to return to Africa. However he persuades her to stay a little longer in the show business. But when three alcoholic costumers give booze to Joe, the gorilla destroys the spot and is sentenced by the justice to be sacrificed. Will Jill, Gregg and Max succeed in saving Joe?” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

King Kong (1933) was a daring and original reinterpretation of the ‘Beauty And The Beast’ theme, in which an adventurous film crew set off to shoot a movie on Skull Island, legendary home of the giant ape known as Kong, worshipped by the locals. Their female lead Ann Darrow (Fay Wray), in a simple twist of fate finds herself offered up as a sacrifice to the fifty-foot tall gorilla by the natives. After a lengthy build-up, Kong eventually reveals himself to be the true star of the film, making off with the convincingly terrified Ann, hauling her up to safety from the ravenous dinosaurs to his mountain retreat. Modern technology eventually allows the crew to rescue Ann and capture the unfortunate Kong, who is taken back to New York to be put on display. He escapes, captures Ann again and climbs up the Empire State Building, where the poor besotted beast is gunned down by airplanes, but not without ensuring Ann’s safety.

The film relies very heavily on the brilliant stop-motion animation techniques developed by Willis O’Brien, who had worked on The Lost World (1925) which vividly bring to life Kong’s island world and his doomed adventures in the Big Apple. Filmmakers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack immediately tried to build on their success with the inferior Son Of Kong (1933) and, after World War Two, re-teamed to film another giant ape script entitled Mister Joseph Young Of Africa. Once again they brought in Kong’s creator O’Brien, who enlisted the aid of model-maker Marcel Delgardo and a young animator named Ray Harryhausen, who had been enthralled with stop-motion animation ever since seeing King Kong in 1933. Harryhausen had made several short films using O’Brien’s techniques, and had shown the veteran effects expert samples of his work. O’Brien felt Harryhausen was ready to work on a major motion picture and, as it developed, Harryhausen was responsible for about eighty percent of the animation scenes with O’Brien acting in a supervisory capacity only.

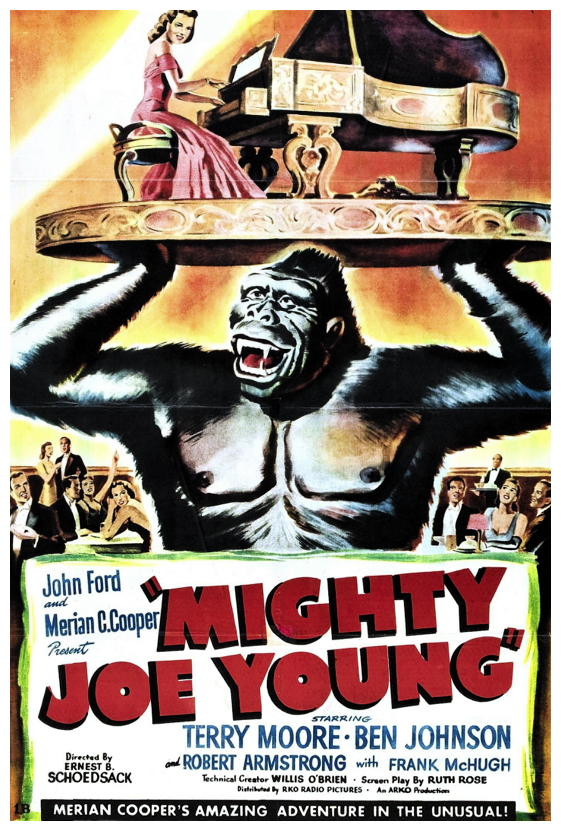

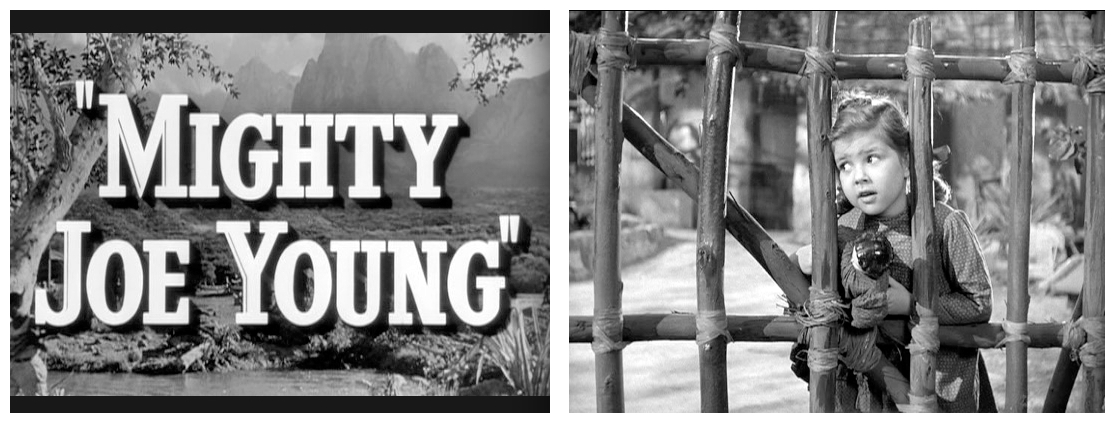

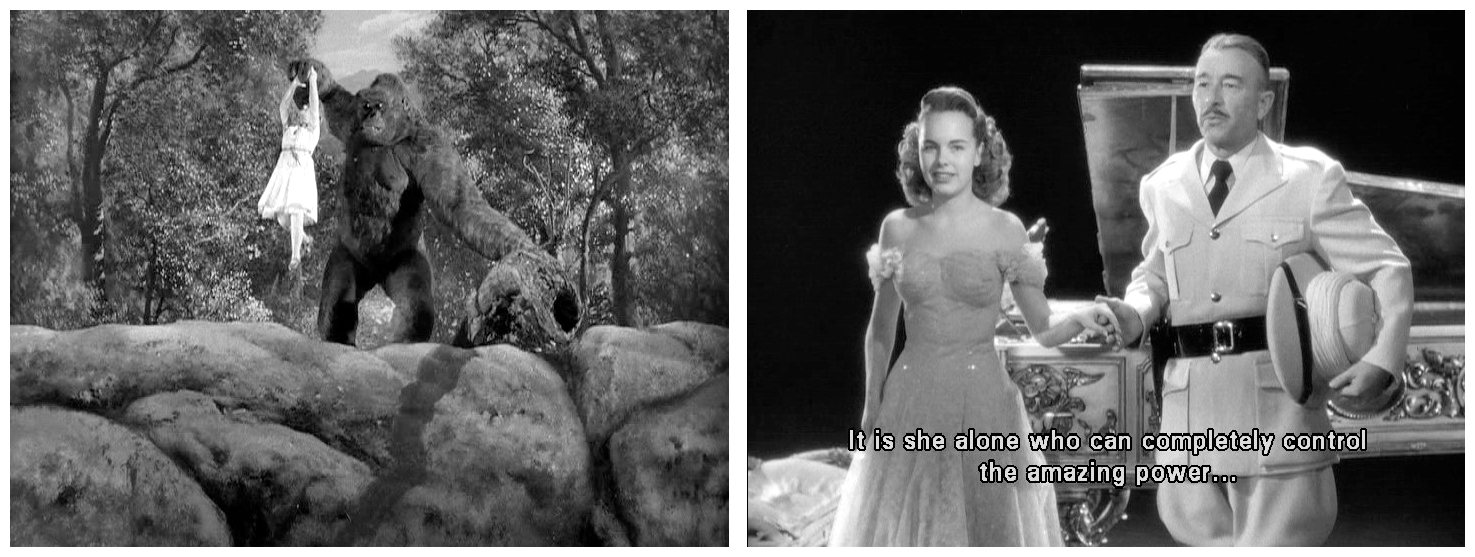

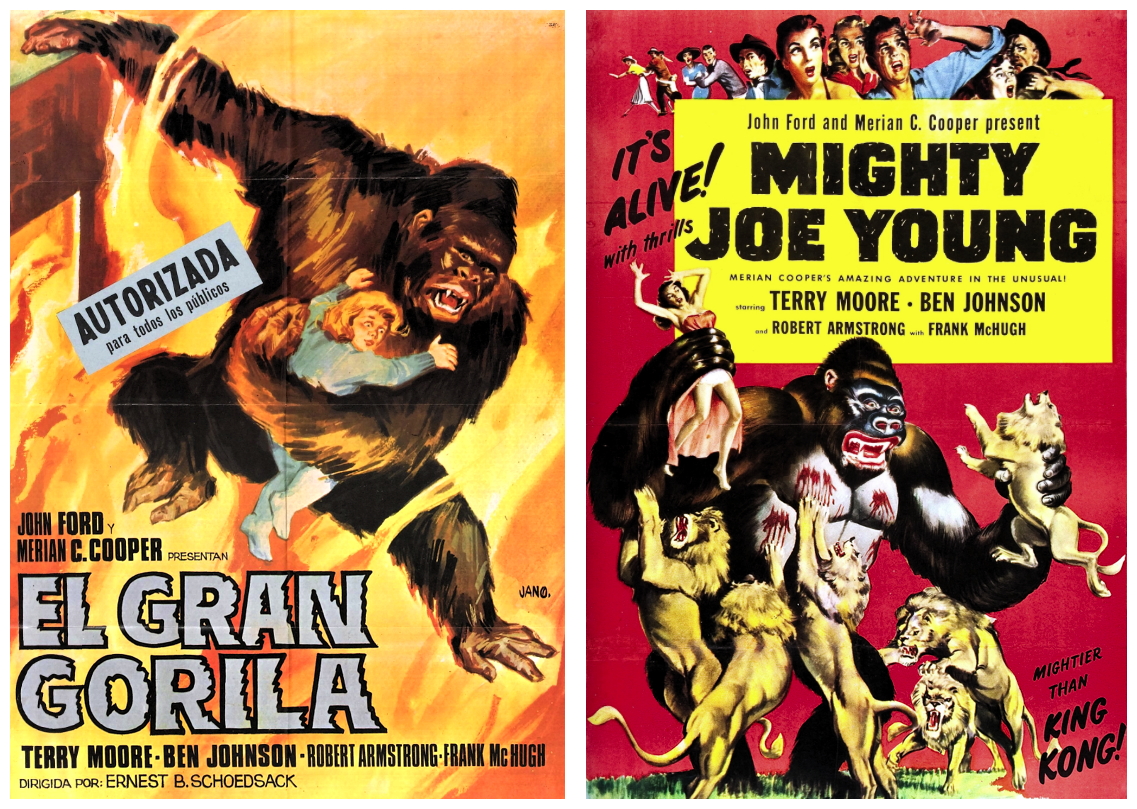

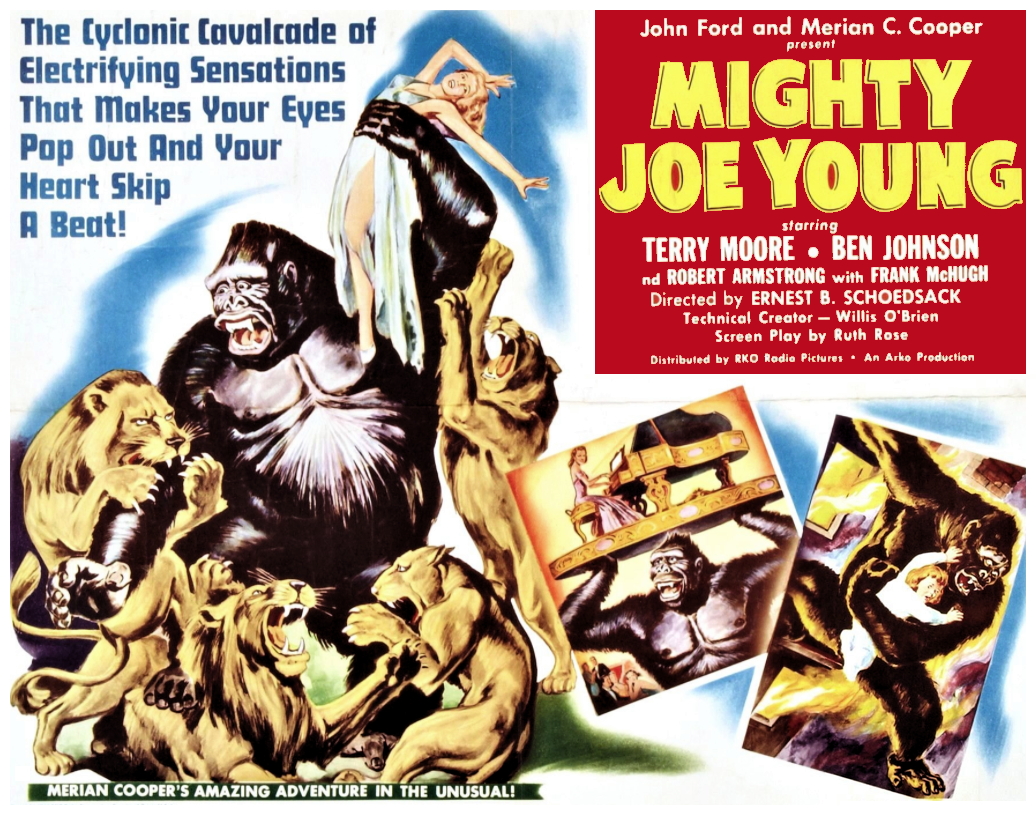

The resulting film, Mighty Joe Young (1949), owes more to Son Of Kong than King Kong, in that the ape is smaller (almost twelve feet tall) and generally used to comic effect. As with Son Of Kong, the film has sadly paled into comparative insignificance next to King Kong, but the animation is the best O’Brien was ever involved with. Joe has grown up in Africa under the care of a pretty little girl named Jill Young, now a young woman (Terry Moore, long-time mistress of billionaire Howard Hughes). New York showman Max O’Hara (Robert Armstrong essentially reprises his role of Kong’s Carl Denham) convinces Jill to come to Broadway where she and Joe will be the main attraction at his nightclub. Beautiful Dreamer, played on a grand piano by fearless Jill, is the ear-worm…I mean, the song that soothes the savage beast, who is not especially savage when he’s treated kindly. Although Jill falls in love with rodeo cowboy Gregg (Ben Johnson), she hates to see Joe so miserable in the big city, regarded as a freak by audiences and being forced to sleep in a cage.

When some rowdy customers get Joe drunk, he wrecks the nightclub and is condemned to be shot. Luckily (if that’s the right word) an orphanage bursts into flame so Joe can save some children and clear his name. Cooper’s much-beloved massive monkey movies, all scripted by Ruth Rose and blessed with O’Brien’s animation, are really in a class of their own. Grandly adventurous in the vein of Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. Rider Haggard and, ultimately, Indiana Jones, these films provided much needed escapism for the reality-beset atomic era, mixing exotic fantasy with two-fisted action and spectacular jaw-dropping special effects. After World War Two, the original Kong creative team was asked to do it all over again, this time with a softer, more storybook approach that seemed to accommodate some of the story’s more outrageous notions. Mighty Joe Young is a western/jungle/monster movie with the charms of a youth-oriented romantic comedy.

Guileless leads Terry Moore and Ben Johnson play like gentle variations of Ann Darrow and Jack Driscoll, while Robert Armstrong himself is back as yet another reckless PT Barnum-type, this time with James Cagney‘s best mate Frank McHugh as his long-suffering sidekick. Also tossed into Cooper’s ingratiating mix is a welcome touch of self-parody, although the campy excesses of Son Of Kong have been carefully avoided. Speaking of which, kids openly cried when baby Kong’s bandaged hand disappeared beneath the churning waves in 1933. Similarly, they gasped in misty-eyed awe as a winded, wounded Joe nearly perishes while rescuing orphans from a burning building. With no Empire State Building to climb in this storyline, Cooper and company devised a substitute that more than delivers, a fiery climax tinted Technicolor amber. O’Hara’s astonishingly cavernous nightclub is another unforgettable creation, with dioramas filled with living African animals (take that, Museum of Natural History!) all spectacularly smashed when Joe goes on his drunken rampage.

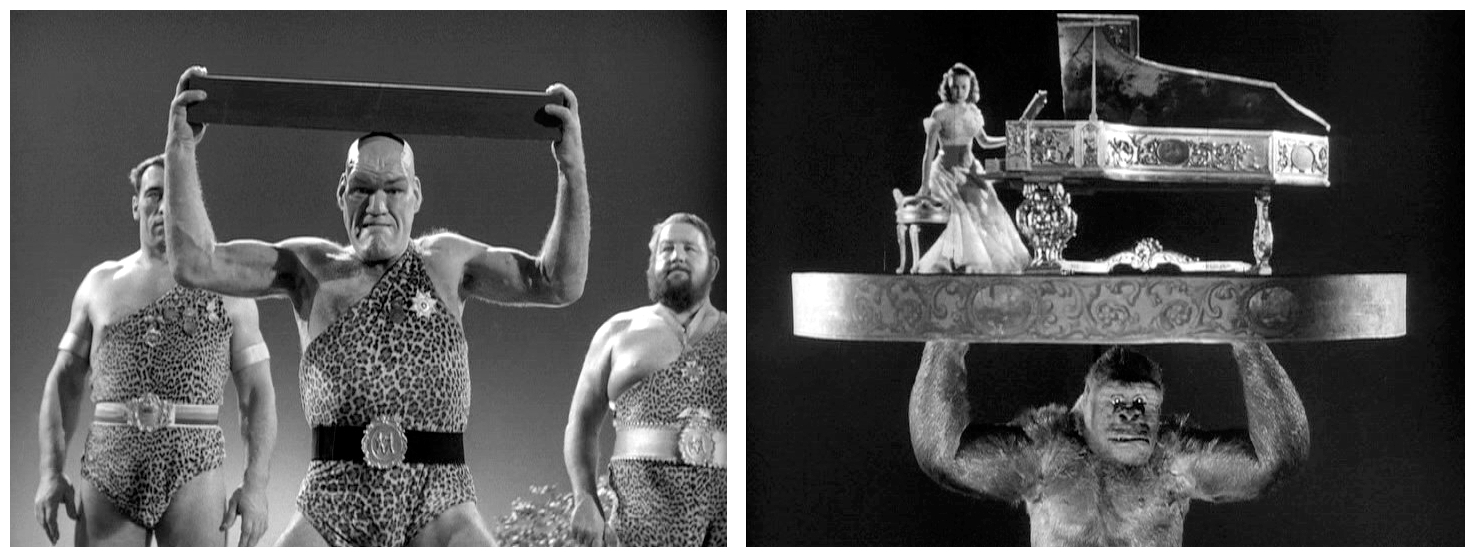

The screenplay by Rose has its ups and downs, but Joe is a fabulously loveable (yet not completely domesticated) creature. The special effects and stop-motion work by O’Brien and Harryhausen are marvellous, and took fourteen months to complete. Joe actually seems real, so subtle are his movements and expressions and, when he snatches a moving child off a burning ledge with a swing of the arm, you’ll be wondering how it was done. One famous scene has Joe winning a tug-of-war contest with several legendary musclemen, including Man Mountain Dean, Primo Carnera and the original Swedish Angel Phil Olafsson. Familiar faces to keep an eye out for include Regis Toomey, Ellen Corby, Richard Farnsworth, Dwayne Hickman, Irene Ryan and William Schallert. Familiar voices to keep an ear out for include the screams of Fay Wray, lifted directly from the soundtrack of King Kong. Photographed by J. Roy Hunt and directed by Schoedsack, ably assisted by one of Hollywood’s greatest filmmakers ever, John Ford, who had so much confidence in the project he took on duties as both executive producer and second-unit director.

Although it lacks the pure driving force of King Kong, Mighty Joe Young has many scenes of complex stop-motion work, not least the exciting burning orphanage sequence. It won for O’Brien a well-deserved Oscar, the award he should have been given for King Kong. A sequel was planned in which Joe would meet Tarzan (Lex Barker), but was shelved due to disappointing box-office returns, barely covering its million-dollar budget. With warmth, humour and future effects superstar Harryhausen as assets, Mighty Joe Young surprised its producers by bombing at the box-office, which is somewhat inexplicable, especially since King Kong would earn its greatest profits when re-released four years later in 1953. But repeated viewings on television assured the film’s status as a legitimate classic, and even a tepid nineties remake from Walt Disney studios couldn’t dull the original’s multi-generational charms. Following Mighty Joe Young, the rest of O’Brien’s career drifted in a sea of unrealised projects and forgettable films.

With his second wife Darlene, O’Brien wrote a script called The Valley Of The Mist, another ‘Lost World’ opus in which a young boy and his pet bull do battle with an allosaurus. It was to be produced by Jesse Lasky, who sold the project to brothers Edward Nassour and William Nassour, after which it was shelved indefinitely. During the fifties Cooper approached O’Brien with a number of proposals, including a remake of King Kong in Cinerama (an unwieldy 3-camera 3-screen process that allowed for beautiful panoramas, but couldn’t do closeups!), and an adaptation of the HG Wells story Food Of The Gods, neither of which, of course, got beyond the drawing-board. Food Of The Gods eventually did make it to the big screen, but under the direction of Hollywood hack Bert I. Gordon, with clumsy full-size models and some of the tackiest blue-screen matte effects of the seventies, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I shall politely ask you to please join me again next week when I have another opportunity to give your cinematic sensibilities a damn good thrashing with the ugly stick for…Horror News! Toodles!

Mighty Joe Young (1949)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews