SYNOPSIS:

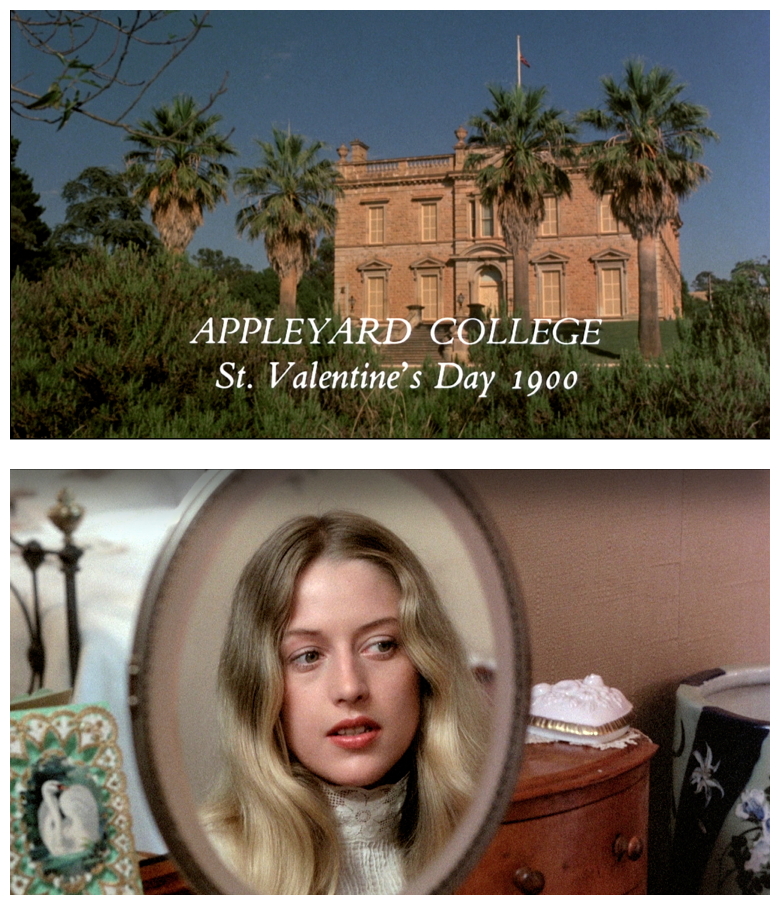

“On Valentine’s Day 1900, most of the small student body and staff of Appleyard College, a private girls’ boarding school in Victoria State, Australia, are going on a day long picnic to nearby Hanging Rock. Two people who will not be going are Mrs Appleyard, the school’s owner and proprietress, and Sara, a student who is being punished for a situation outside of her control. Later that evening, the picnickers arrive back to the college later than expected minus four people: teacher Miss McCraw, and students Miranda, Irma and Marion, all of who have gone missing. The three girls plus a tag-along student, Emily, went exploring up the rock, when Emily came rushing off the rock by herself in a frightened panic, with several cuts and bruises and her dress torn. By that time, no one had noticed that Miss McCraw had also gone missing. Emily cannot remember anything about the incident beyond seeing Miss McCraw off in the distance climbing up the rock when she herself was heading down. As the authorities go on an exhaustive search for the missing four, their disappearance elicits different reactions from people involved. Michael Fitzhubert, a young well off man who, along with his valet Albert, saw the four girls climbing up the rock, and feels compelled to find them. Sara, who idolised Miranda, is quietly affected as she keeps several secrets about herself and what Miranda told her earlier that day. And Mrs Appleyard, although concerned about the welfare of the missing four, seems more concerned about the possibly tarnished reputation of the school, to which her name is attached, and the affect the scandal may have on its viability.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

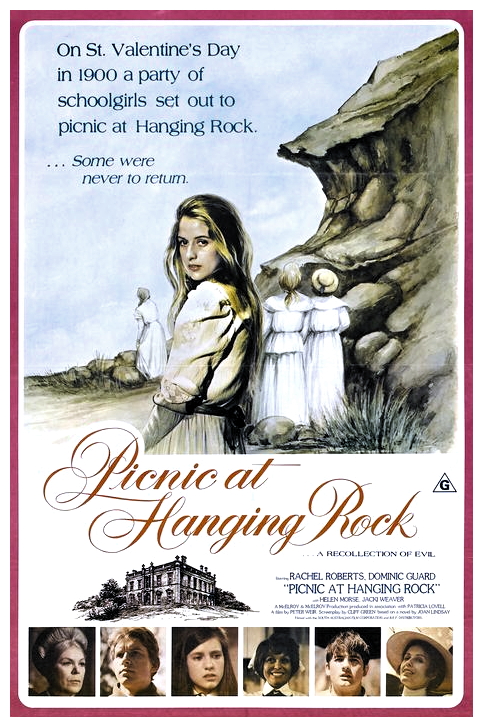

Horror takes much of its vividness from dualisms, tensions between opposites, often symbolised by the meeting of two very different worlds. A similar tension to that between modern and ancient is that between the rational and the irrational, the routine and the mysterious. At the heart of many horror films is the mysterious protruding into the banalities of everyday life. To enter such a mystery is often to find that the inside is bigger than the outside. One small item of irrationality opens a door to a maze which becomes wilder the more deeply it is explored. This is the central image of Picnic At Hanging Rock (1975) directed by Peter Weir.

One of Australia’s seventies New Wave directors and something of a poet of emotional and physical claustrophobia, Weir became adept at maintaining the basic integrity of his films while still scoring success at the box office. Gallipoli (1981) followed cinema’s tradition of historical inaccuracy, but was emotionally on-target. The Year Of Living Dangerously (1983) successfully conjured up an entire lost decade that may be close to us in time but far away in comprehension, and Master And Commander (2003) fastidiously recreated life on board an early nineteenth century Man-Of-War. Other career highlights include Witness (1985), Dead Poets Society (1989), Green Card (1990), Fearless (1993), and The Truman Show (1998).

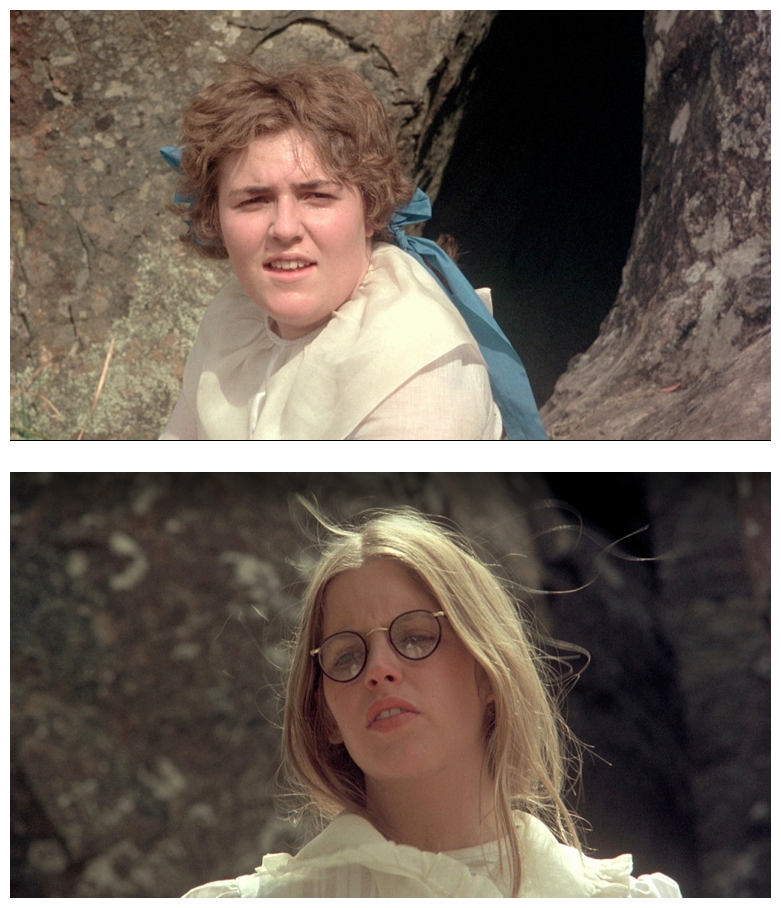

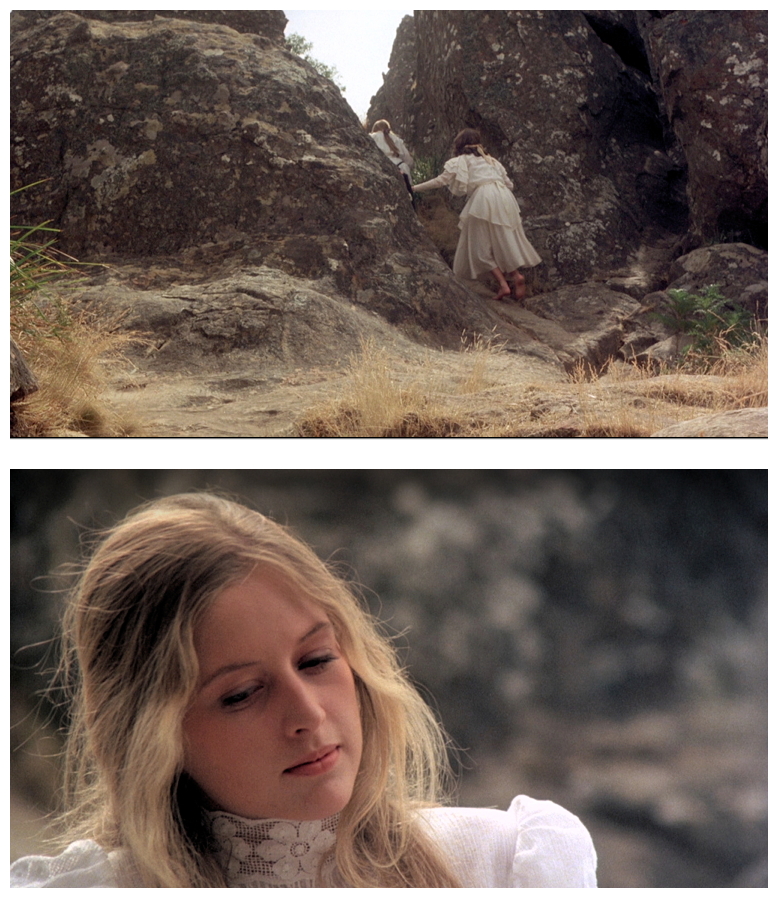

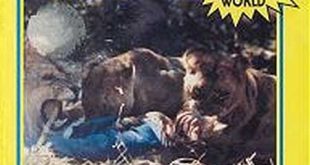

The opening line in Picnic At Hanging Rock, spoken by Miranda (Anne-Louise Lambert), quotes Edgar Allan Poe: “What we see and what we seem are but a dream, a dream within a dream.” On Valentine’s Day 1900, a group of normal chattering schoolgirls from a rather posh boarding school set out on a picnic in a rural area of Victoria, Australia. Once at Hanging Rock they find that their watches have stopped at exactly twelve noon (the door that leads out of the everyday has just been opened). Four of the more active girls ascend to the weirdly contorted top of the hill. The first three disappear into thin air, the fourth, a struggling chubby girl, is left behind. The rest of the film circles like some fluttering bird, around this oasis of enigma in the desert of routine. Its mystery only deepened when one of the girls reappears, her memory wiped.

Why were these girls taken and not the others? Was it something to do with sexuality? A series of blandly impervious images offers tantalising hints but no explanation. The camera explores the natural world near the school with grace and lyricism, vignettes of upper-class life are photographed to look like Fin de siècle academy pictures by Tissot – all straw hats, long dresses, autumn leaves and rippling water. Darker images intrude, schoolgirl propriety suddenly erupts into screaming hysteria, the relentless buzzing of blowflies portends the discovery of a suicide’s body. The red of carnality obtrudes on the pastels of chastity. Cinematographer Russell Boyd enhanced the film’s diffuse and ethereal look by simply placing a bridal veil over the camera lens, and composer Bruce Smeaton‘s haunting score hums like a call from another dimension.

The film’s opening sequence (girls wash in flower-scented water, whisper among themselves, hold hands, blow kisses, read poetry, exchange valentines and help each other tie their corsets while director Weir inserts cold austere shots of the unfriendly school) conveys that domineering Mrs Applyard’s (Rachel Roberts) school is not so much a finishing school as an institute for sexual repression. The ascent of the dazed dressed-in-white virgins through the surreal rock formations (phallic boulders merge with shots of narrow virginal passageways) and their subsequent disappearance represents both their rite of passage into sexual womanhood and an escape into another world where there is no sexual repression.

The key is the lovely Miranda, who is not of this world. She is the embodiment of sexual desire stifled, as was her namesake in The Tempest by William Shakespeare. She is like a Peter Pan whose mission is to deliver herself and three other sexually repressed females into a sexual never-never land, far away from adults like Mrs Appleyard and the uncaring parents who would entrust them to such a witch. The first part of the film is absolutely spellbinding with a sinister atmosphere but, compared to what happens at Hanging Rock, everything that comes afterward is a little anticlimactic, despite an excellent cast that includes Vivean Gray, Dominic Guard, Tony-Llewellyn Jones, John Larrett, Helen Morse, Margaret Nelson, Karen Robinson, Jane Vallis and Jacki Weaver (recently seen supporting Patrick Stewart in the Seth MacFarlane comedy series Blunt Talk).

It is quite a remarkable film, weaving its intricate elegant variations, playing games with Freud and Marx and even the possibility of flying saucers, to tease us about a mystery whose whole point must be that it remains a mystery. The unsolvable mystery of the disappearances was arguably the key to the success of both the novel Picnic At Hanging Rock (published 1967) by Joan Lindsay and the subsequent film. This aroused enough interest that a book of hypothetical solutions was released entitled The Murders At Hanging Rock (published 1980) by Yvonne Rousseau. The novel is written in the form of a true story, with a pseudo-historical prologue and epilogue, adding to the overall feeling of mystery. However, while the geological feature known as Hanging Rock and the towns mentioned are actual places, the story is entirely fictitious.

Lindsay’s original draft of the novel included a final chapter in which the mystery was resolved, but her editor demanded that it be removed. In missing chapter eighteen, the girls become dizzy and feel as they are being pulled from the inside out. They throw their corsets from the top of the cliff but, instead of falling, the corsets stand still in mid-air. They then encounter a hole in space, by which they physically enter a crack in the rock. This time-warp explains the author’s many references to clocks and time. In fact Lindsay was known amongst her friends for being able to stop watches and clocks in her vicinity, a phenomenon that occurred and was recorded many times during her life. It’s with this bombshell I’ll politely ask you to please join me next week to have your innocence violated beyond description again while I force you to submit to the horrific horrors of…Horror News! Toodles!

Picnic At Hanging Rock (1975)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

“Lindsay’s original draft of the novel included a final chapter in which the mystery was resolved, but her editor demanded that it be removed.”

The idea of a ‘final’ or ‘missing chapter’ is based on hearsay only. Three years after Lindsay’s death, her editor presented a text which he attributed to Lindsay, with the story of it having been withdrawn at his advice.

The problem is: there is no material proof for his assertion. No manuscript. No annotated typoscript. No correspondence between Lindsay and her author. No diary entry by Lindsay. No transfer of rights by her. No notary document. No last will entry.

As said; the story is based on hearsay.

Yet we can see and hear Joan Lindsay being interviewed about ‘Picnic’ and explicitly saying that she never wrote ‘a solution’ to the mystery presented in her book. She conceived the novel as open-ended, in the same vein as Henry James ‘The Turn of the Screw’ (Lindsay mentioned this example). It was totally fascinating to her how people simply could not accept that no ‘solution’ ever existed, and that readers should use their imagination.

So here is our dilemma: do we believe Lindsay, or her editor? Given the total absence of material proof for his attribution, any rational scientist would not hesitate to deem that ’18th chapter’ a literary hoax, as there have been so many literary hoaxes and false attributions in the history of literature. I am sure that the editor made a good buck by the sale of ‘The Secret of Hanging Rock’ and the renewed interest in ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’ – three years after Lindsay’s death, so she was conveniently not around anymore to refute the authenticity of that ’18th chapter’.

Thanks for reading, and the intricate, intelligent comment. I don’t think we can be entirely sure one way or the other but, as I mention, it would certainly explain her references to clocks and time in the novel, as well as her own personal experiences. I had read articles and checked Wikipedia, of course, but I decided to go with the most straightforward explanation.