SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Walter Craig, an architect, is summoned down to a house called Pilgrim’s Farm by a prospective client whom he does not know. On arrival he experiences strongly the feeling that he has been to the place before. He is taken into the house and introduced by his host to a group of people. These also are familiar, though none of them appear to know him. After somewhat constrained greetings he tells them that he has met them all, and the house, and the situation, is a recurring dream. He explains how this dream always starts quietly and pleasantly – at the present moment – but after a certain small incident invariably begins to darken into ghastly nightmare, culminating in horror – a horror of his own creation – from which he wakes up sweating with fear. He never remembers his dream for more than a few moments after waking, until the next time it occurs. He then describes the incident which will mark the turning point of his dream – the breaking of a pair of glasses belonging to one of the party, a psychiatrist. Increasingly fascinated, the party one by one reveal that each has at some time undergone an inexplicable experience. The narration of these make up the body of the film.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

A current cliche tells us that modern horror films suffer from being too literally horrible (blood and gore) and that things were done better in the olden days, when horror was conveyed by subtlety and implication, and the cold chill that resulted was because the viewer’s own imagination was allowed to conjure up sinister shapes that were only hinted at. The weakness of this viewpoint is clearly seen in films like The Uninvited (1944) – all atmosphere and no real substance. The big-budgeted Hollywood fantasy productions of the forties shunned the monsters that dominated the previous decade, but retained an interest in ghosts. Portrait Of Jennie (1948), for example, is a better film than The Uninvited, and its romanticism strikes deeper. Portrait Of Jennie won an Oscar for its special effects, but was not a huge commercial success because, fundamentally, it is a rather European film about unhappiness and failure. It is sensitively made and compelling, however, and over the years has quietly assumed the status of a minor supernatural classic.

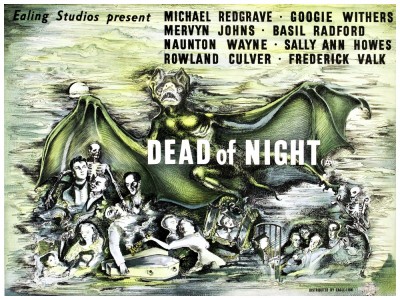

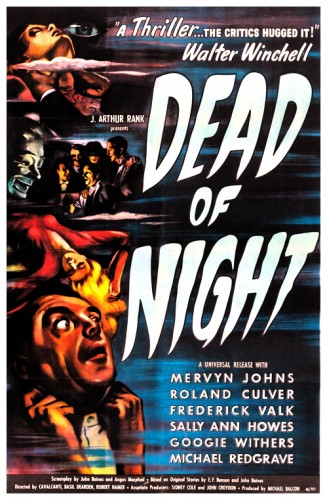

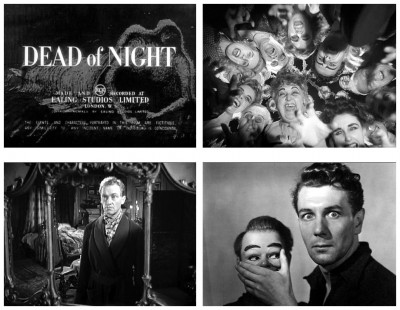

So too has an unusual English essay in the well-bred ghost-story film Dead Of Night (1945), featuring five brief supernatural tales linked by a sixth story of an architect’s recurring nightmare which at the very end (sometimes missed because the final credits have already rolled) turns out to be possibly true. This seminal horror anthology film is where you’ll discover the cinematic origins of several of the creepiest you’ve seen on television since the fifties. An architect (Mervyn Johns) finds himself invited to a large mansion. The strangers inside are the people he’s been seeing in his nightmares. While he waits for disaster to begin, just as in his nightmare, other guests ask a skeptical psychiatrist (Frederick Valk) to explain the strange experiences they’ve had. Five supernatural tales are then told.

So too has an unusual English essay in the well-bred ghost-story film Dead Of Night (1945), featuring five brief supernatural tales linked by a sixth story of an architect’s recurring nightmare which at the very end (sometimes missed because the final credits have already rolled) turns out to be possibly true. This seminal horror anthology film is where you’ll discover the cinematic origins of several of the creepiest you’ve seen on television since the fifties. An architect (Mervyn Johns) finds himself invited to a large mansion. The strangers inside are the people he’s been seeing in his nightmares. While he waits for disaster to begin, just as in his nightmare, other guests ask a skeptical psychiatrist (Frederick Valk) to explain the strange experiences they’ve had. Five supernatural tales are then told.

Basil Dearden directs the framing story as well as the first episode entitled Hearse Driver, a retelling of the original urban legend better known as Room For One More, in which a hospital patient (Anthony Baird) has a spooky vision that later saves his life. Golfing Story is a light-hearted tale from the director of A Fish Called Wanda (1988), Charles Crichton, about two obsessed golfers named Parratt (Basil Radford) and Potter (Naunton Wayne), one of whom becomes haunted by the other’s ghost. Based on a short story by my old friend H.G. Wells, these very English characters are derivatives of Charters and Caldicott, created for the Alfred Hitchcock film The Lady Vanishes (1938). The double-act proved to be so popular that Radford and Wayne were paired up as similar sport-obsessed gentlemen in a number of productions, including this one. The changed names neatly sidestepped any copyright issues.

Basil Dearden directs the framing story as well as the first episode entitled Hearse Driver, a retelling of the original urban legend better known as Room For One More, in which a hospital patient (Anthony Baird) has a spooky vision that later saves his life. Golfing Story is a light-hearted tale from the director of A Fish Called Wanda (1988), Charles Crichton, about two obsessed golfers named Parratt (Basil Radford) and Potter (Naunton Wayne), one of whom becomes haunted by the other’s ghost. Based on a short story by my old friend H.G. Wells, these very English characters are derivatives of Charters and Caldicott, created for the Alfred Hitchcock film The Lady Vanishes (1938). The double-act proved to be so popular that Radford and Wayne were paired up as similar sport-obsessed gentlemen in a number of productions, including this one. The changed names neatly sidestepped any copyright issues.

Two of the best stories are directed by Alberto Cavalcanti. In Christmas Party, a young woman (Sally Ann Howes) comforts a sobbing little boy (Michael Allan) in another room where the party is being held, only to learn that he had been murdered years ago by his sister. This particular ghost story is loosely based on a real-life murder mystery. In 1860, Francis Saville Kent (only four years old) was murdered, and his sixteen-year-old half-sister Constance Kent later confessed to the crime. Due to a lack of evidence in the case, she wasn’t actually arrested and put on trial until 1865. The case garnered national attention in the United Kingdom and was partially responsible for the birth of modern detective techniques and the popularity of fictional sleuths such as Sherlock Holmes and his rivals. Unfortunately, American distributors considered the original print of the film too long, so Golfing Story and Christmas Party were cut. This only confused audiences who couldn’t understand why Michael Allan, from Christmas Party, was in the framing story.

Two of the best stories are directed by Alberto Cavalcanti. In Christmas Party, a young woman (Sally Ann Howes) comforts a sobbing little boy (Michael Allan) in another room where the party is being held, only to learn that he had been murdered years ago by his sister. This particular ghost story is loosely based on a real-life murder mystery. In 1860, Francis Saville Kent (only four years old) was murdered, and his sixteen-year-old half-sister Constance Kent later confessed to the crime. Due to a lack of evidence in the case, she wasn’t actually arrested and put on trial until 1865. The case garnered national attention in the United Kingdom and was partially responsible for the birth of modern detective techniques and the popularity of fictional sleuths such as Sherlock Holmes and his rivals. Unfortunately, American distributors considered the original print of the film too long, so Golfing Story and Christmas Party were cut. This only confused audiences who couldn’t understand why Michael Allan, from Christmas Party, was in the framing story.

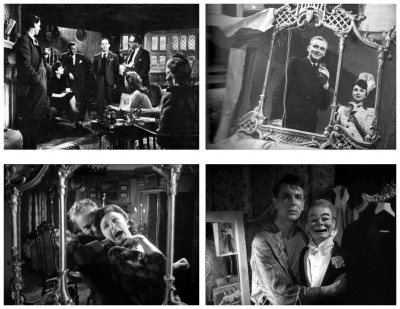

The other Cavalcanti episode deservedly became the most famous. Actor Michael Redgrave plays a nervous ventriloquist who becomes increasingly insane from worrying that his dummy – a foul-mouthed unpleasant-looking wooden fellow named Hugo – is looking for a new partner. He descends into madness as Hugo comes to life, eventually speaking and acting with all the mannerisms of the dummy that has possessed him. Most ventriloquist stories are terrifying, but this one really make me jittery. That being said, the strongest episode is arguably Haunted Mirror directed by Robert Hamer, concerning a young urban couple (Ralph Michael and Googie Withers) in the 20th century who are influenced by an antique mirror within which a sinister 19th century atmosphere is reflected, including the previous owner, a jealous maniac who strangled his wife. The maniac eventually possesses and destroys the soul of the young husband – the film’s biggest jolt comes when he starts to strangle his own wife and she looks into the mirror at a startling image.

The other Cavalcanti episode deservedly became the most famous. Actor Michael Redgrave plays a nervous ventriloquist who becomes increasingly insane from worrying that his dummy – a foul-mouthed unpleasant-looking wooden fellow named Hugo – is looking for a new partner. He descends into madness as Hugo comes to life, eventually speaking and acting with all the mannerisms of the dummy that has possessed him. Most ventriloquist stories are terrifying, but this one really make me jittery. That being said, the strongest episode is arguably Haunted Mirror directed by Robert Hamer, concerning a young urban couple (Ralph Michael and Googie Withers) in the 20th century who are influenced by an antique mirror within which a sinister 19th century atmosphere is reflected, including the previous owner, a jealous maniac who strangled his wife. The maniac eventually possesses and destroys the soul of the young husband – the film’s biggest jolt comes when he starts to strangle his own wife and she looks into the mirror at a startling image.

The entire film is remarkably restrained, though atmospheric in its depiction of mainly upper-class horrors. Horror films were heavily censored in the United Kingdom from 1937 to 1950, given a ‘H’ certificate indicating Horror content, to restrict them to people sixteen years of age or older (before 1937 they were all rated ‘O’ for ‘Orror – or so I was told). Some films were banned outright, such as Freaks (1932) and Island Of Lost Souls (1932), or mercilessly censored as King Kong (1933) was, losing the close-ups in which Kong steps on natives and chews on people. The release of ‘H’ certificate films was totally banned between 1942 and 1945, so the making of Dead Of Night (while World War Two was still raging) was an act of courage, and it’s not surprising if parts of it seem so tasteful today as to be almost prissy. The endeavour was a success and the censor rewarded an obviously good film by merely giving it an ‘A’ certification, meaning it could be viewed by younger people in the company of an adult.

The entire film is remarkably restrained, though atmospheric in its depiction of mainly upper-class horrors. Horror films were heavily censored in the United Kingdom from 1937 to 1950, given a ‘H’ certificate indicating Horror content, to restrict them to people sixteen years of age or older (before 1937 they were all rated ‘O’ for ‘Orror – or so I was told). Some films were banned outright, such as Freaks (1932) and Island Of Lost Souls (1932), or mercilessly censored as King Kong (1933) was, losing the close-ups in which Kong steps on natives and chews on people. The release of ‘H’ certificate films was totally banned between 1942 and 1945, so the making of Dead Of Night (while World War Two was still raging) was an act of courage, and it’s not surprising if parts of it seem so tasteful today as to be almost prissy. The endeavour was a success and the censor rewarded an obviously good film by merely giving it an ‘A’ certification, meaning it could be viewed by younger people in the company of an adult.

Near the end of the film, the architect wakes up, revealing that it has all been a dream. Therefore, the five stories in the film are flashbacks, essentially dreams within the dream. Furthermore, the Ventriloquist Dummy story also includes a flashback, which means that it is a flashback within a flashback (or a dream within a dream). This may sound a little confusing, but you may be surprised to hear that Dead Of Night, an anthology of ghost stories, inspired one of the more important theories in the science of astronomy. A trio of famous cosmologists – Fred Hoyle, Thomas Gold and Hermann Bondi – developed the Steady State Theory of the universe (an alternative to the Big Bang Theory) after seeing this film, and stated that the circular nature of the plot inspired their model.

Near the end of the film, the architect wakes up, revealing that it has all been a dream. Therefore, the five stories in the film are flashbacks, essentially dreams within the dream. Furthermore, the Ventriloquist Dummy story also includes a flashback, which means that it is a flashback within a flashback (or a dream within a dream). This may sound a little confusing, but you may be surprised to hear that Dead Of Night, an anthology of ghost stories, inspired one of the more important theories in the science of astronomy. A trio of famous cosmologists – Fred Hoyle, Thomas Gold and Hermann Bondi – developed the Steady State Theory of the universe (an alternative to the Big Bang Theory) after seeing this film, and stated that the circular nature of the plot inspired their model.

The strong Shakespearean-trained British cast also includes Roland Culver, Judy Kelly, Miles Matheson, Mary Merrall, Renee Gadd, Peggy Bryan and Hartley Power, but one of the most interesting people involved with the production of the film could only be found behind the camera: Cinematographer Douglas Slocombe OBE cut his industry teeth at Ealing Studios, and Dead Of Night was his first full-length motion picture. Born in 1913 (yes folks, this one’s still alive!) he photographed more than eighty films in less than half a century before his retirement in 1989, including the original serial-killer comedy Kind Hearts And Coronets (1949), The Man In The White Suit, The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953).

The strong Shakespearean-trained British cast also includes Roland Culver, Judy Kelly, Miles Matheson, Mary Merrall, Renee Gadd, Peggy Bryan and Hartley Power, but one of the most interesting people involved with the production of the film could only be found behind the camera: Cinematographer Douglas Slocombe OBE cut his industry teeth at Ealing Studios, and Dead Of Night was his first full-length motion picture. Born in 1913 (yes folks, this one’s still alive!) he photographed more than eighty films in less than half a century before his retirement in 1989, including the original serial-killer comedy Kind Hearts And Coronets (1949), The Man In The White Suit, The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953).

Slocombe won the BAFTA Best Cinematography award for The Servant (1963), The Great Gatsby (1974) and Julia (1977), and was nominated for Guns At Batasi (1964), The Blue Max (1966), The Lion In Winter (1968), Travels With My Aunt (1973), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), Rollerball (1975), Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984) and Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989). He has also won the British Society of Cinematographers award five times, and was finally presented with their Lifetime Achievement award in 1996. Despite this incredible body of work, he has only ever been nominated for three Oscars, winning none whatsoever. I’ll allow you to mull over the questionable judgment of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the next seven days, and I’ll vanish mysteriously into the night, but not before inviting you to rendezvous with me at the same time next week when I’ll discuss another dubious treasure for…Horror News! Toodles!

Slocombe won the BAFTA Best Cinematography award for The Servant (1963), The Great Gatsby (1974) and Julia (1977), and was nominated for Guns At Batasi (1964), The Blue Max (1966), The Lion In Winter (1968), Travels With My Aunt (1973), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), Rollerball (1975), Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984) and Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989). He has also won the British Society of Cinematographers award five times, and was finally presented with their Lifetime Achievement award in 1996. Despite this incredible body of work, he has only ever been nominated for three Oscars, winning none whatsoever. I’ll allow you to mull over the questionable judgment of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the next seven days, and I’ll vanish mysteriously into the night, but not before inviting you to rendezvous with me at the same time next week when I’ll discuss another dubious treasure for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews