SYNOPSIS:

“The year is 2018. There is no crime and there are no more wars. Corporations are now the leaders of the world, as well as the controllers of the people. A violent futuristic game known as Rollerball is now the recreational sport of the world, with teams representing various areas competing for the title of champion. The defending championship team – the Houston team led by the determined ten-year veteran Jonathan E. – is looking to repeat as champions. However, Bartholomew, the sinister corporate head, wants Jonathan to retire, even though he is the most respected athlete of his time. Jonathan’s rebellious quest will not come out with complications, both for him and his teammates, after he decides to continue playing despite Bartholomew’s threats.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

One theme you’d think would be too depressing to be considered entertainment is life after the collapse of civilisation as we know it – after nuclear war, or zombie plague, or ecological disaster, or something simpler like running out of fossil fuels. Oddly enough, such films can have their upbeat moments too. A lunatic sub-genre of future dystopia cinema is the ‘bread-and-circus’ killer-sports films. Two of the best-remembered were released the same year. The cheap one, Death Race 2000 (1975), was made to cash-in on the publicity for the expensive one, Rollerball (1975). Actually, the low-budget shocker from New World Pictures, produced by the shrewd old king of exploitation, Roger Corman, is considered by many to be the better film. The script is amusing and, because the film does not take its absurd premise too seriously, it’s all good dirty fun. Rollerball, on the other hand, takes itself very seriously indeed. Four decades ago, Rollerball was one of the last big-budget pre-Star Wars science fiction films, a work which spanned many genres but remained deeply rooted in the lengthy literary traditions of true speculative fiction. Directed by Norman Jewison, Rollerball is set in a seemingly blissful utopian near-future where the bloodthirstiness of the coddled masses is placated with the brutal sporting event of the film’s title.

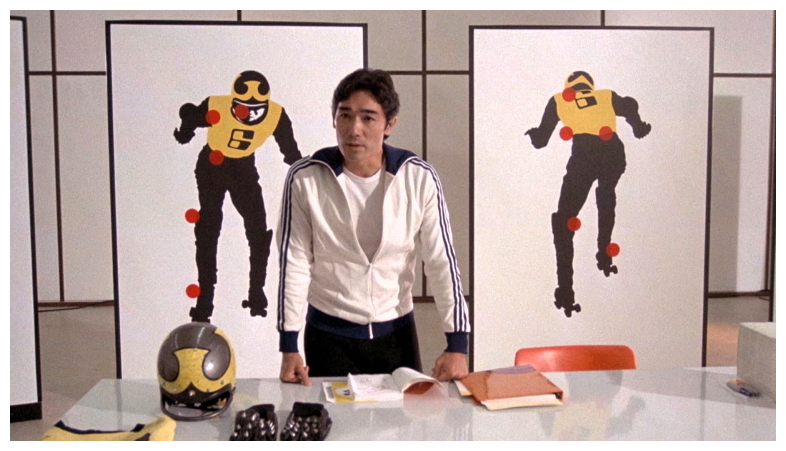

Thematically the film deals with what its director called, “The fight for the very freedom to exist.” Visually, the primary influence was A Clockwork Orange (1971), most obvious in its frequent use of zooms, modern architecture and classical music. While changing fashions and unimaginable advances in computer technology date the film badly, Rollerball seems more relevant in the pay-per-view blood-sporting trial-by-media of today than it was in the tumultuous decade of its original release. Based on his own short story, screenwriter William Harrison credibly establishes the film’s futuristic milieu. Set in the far-flung future year of 2018, sometime after the ‘Corporate Wars’, nations are bankrupt and the world is run by massive corporations based in various cities around the globe. These conglomerates (Energy, Food, Information, Luxuries, Transport, etc.) keep the planet’s economy going. To ensure the population’s instinctive need for conflict never spills over to disrupt their carefully balanced society, the corporations have created Rollerball, a shockingly brutal cross between football, basketball, roller derby, and Roman gladiatorial combat. The game has only one purpose – to demonstrate the futility of individual effort. To this end, nationalism has been completely eradicated, replaced instead by team spirit, and the people love it.

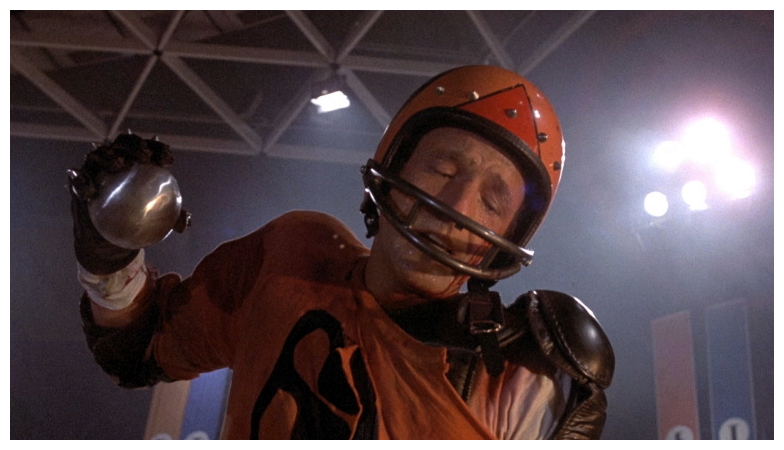

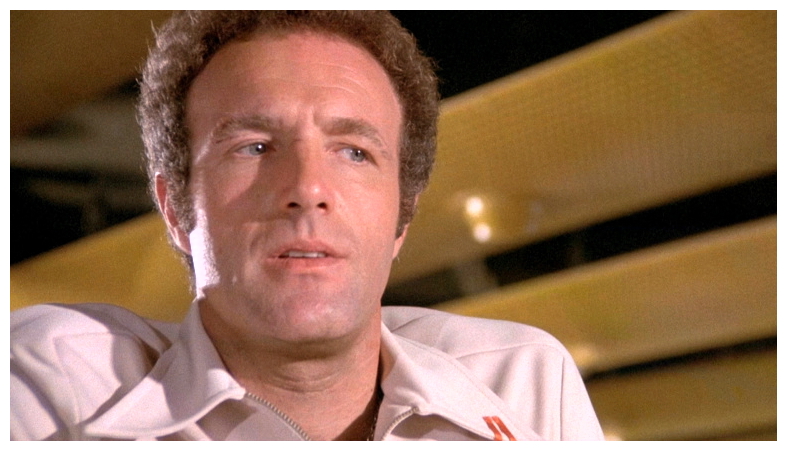

The storyline, despite its many genre trappings, is quite simple. Jonathan E. (James Caan), captain of the Houston-based Energy Corporation’s Rollerball team, has survived the game for over ten years, making him the greatest player ever. But no player is supposed to be greater than the game itself and, as the latest season draws to a close, the CEO of the Energy Corporation, Bartholomew (fatherly John Houseman) demands without explanation that Jonathan quit playing. Not understanding why, Jonathan refuses and embarks on a quest to learn who ultimately controls the game and why they want him to quit. As Jonathan begins to unravel the intricacies of corporate decision-making, the rules of Rollerball itself are changed by the corporations hoping the game becomes so deadly that not even the great Jonathan can survive. Jonathan, however, plays on. Not surprisingly, the three breathtaking Rollerball sequences themselves are the heart of the film.

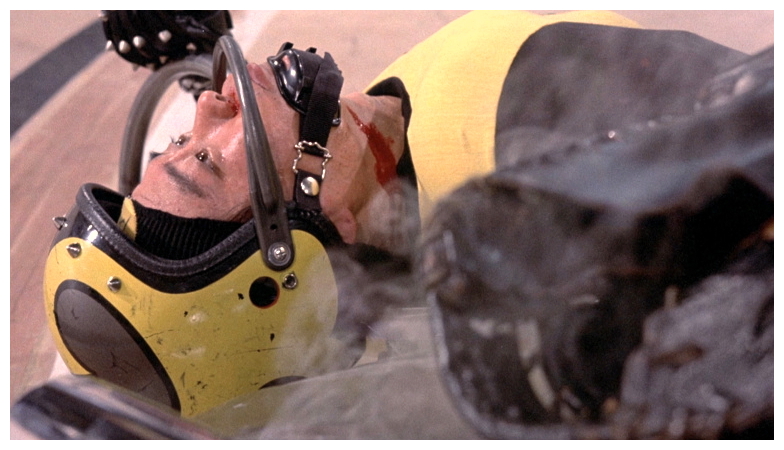

From the production design to the attention paid to every detail of this non-existent sport (the rules of the game were so thoroughly realistic that cast and crew would often play a few rounds between takes), these moments are some of the very best of seventies cinema. Masterfully shot by Douglas Slocombe (who later became Steven Spielberg‘s favourite cinematographer), they have a rough documentary style to them reminiscent of old sports movies, creating a look and realism sadly lacking in much of today’s Hollywood action cinema, pummelling the audience with every blood-drenched blow. Death is a reality here, but Jewison had to be careful that he didn’t turn the audience on with the violence, but turn them off. He succeeds admirably. Rather than cheer as a motorcycle runs over a downed player, one can’t help but wince over the broken body. The complete lack of music during these sequences, leaving the filmmakers to rely only on editing and their filmic coverage of the scenes, testifies to their success. Like Ridley Scott‘s Blade Runner (1982) and its sequel, Rollerball works best when delving into its own fictitious world and less so when building plot, drama and characterisation.

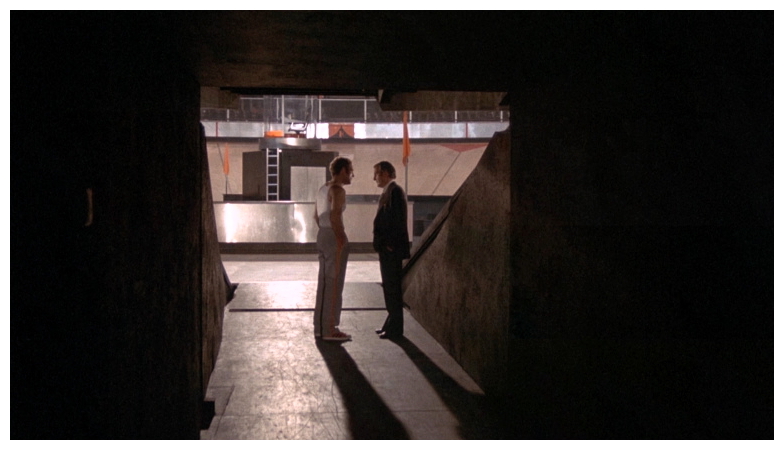

Ella (Maud Adams), the ex-wife Jonathan never stopped loving even after she was taken away by an executive who wanted her, best sums up the philosophy of the film’s future, explaining the whole of human history has been a struggle against poverty and need. The corporations gave humanity a choice between comfort and freedom. Of course, mankind opted for comfort, bought off with increased privilege and lack of want. The corporations devised the game as a means of keeping the population under control, the idea being that if people are able to watch men on skates beating each other up, they won’t want to indulge in any awkward political activity. While corporate executives represent a new upper class, race and poverty no longer divide the world, leaving everyone free to enjoy days filled with trips to luxury centres full of edited and transcribed books and other media. However, the Rollerball players are portrayed as this future’s new slave class. While the players lead lives of increased privilege, they are looked down upon by almost everyone.

At a party for Jonathan’s ‘multi-vision’ TV special, an executive looks around at the players, quipping to his date in a display of superiority to, “Smell the lions.” Bartholomew himself explains that executives dream of giving in to their baser instincts by taking drugs and dreaming that they are great Rollerballers, they have muscles, and they bash in faces. Of course, executives are far too refined to ever actually carry out such desires. Even when a celebrity of Jonathan’s stature goes looking for unexpurgated reading material, a lowly clerk explains that a person like him would have little use for such material. The film relies heavily on established science fiction tropes. The paranoid fear of computer technology remains pervasive throughout Rollerball. As in the earlier 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), the film ridiculously insinuates the encompassing presence of computers will ultimately spell certain doom for the human race. During one out-of-place tacked-on sequence, Jonathan travels to Geneva to consult with the ‘fluidic’ computers there.

He meets a strange librarian (amusingly portrayed by Ralph Richardson) and his master computer ZERO, the world’s most advanced mainframe. After learning that ZERO has misplaced records pertaining to the entire 13th Century earlier that day (“Not much in the 13th Century, just Dante and a few corrupt Popes…”) Jonathan asks it about who makes corporate decisions. This only confuses the poor old mainframe. Making excuses for the clearly insane ZERO, the librarian explains that everything has become so very difficult for the computer to ingest, and its answers are so ambiguous they’re virtually meaningless: “It’s as if he knows nothing at all.” While the notion of over-complication and too much information seems more valid today than ever before, corporations themselves seem far more dangerous than any personal device could ever be. One of the film’s more curious conceits, especially looking back from today’s politically-correct perspective, are the roles women play in the movie. Although a woman does sit on the Corporate ruling council, for the most part females remain little more than tools and fashion accessories traded back and forth by both the male executives and the Rollerball players.

The future, it seems, allows women only the freedom to exist as little more than bedside tissues, thrown away after the act is over, needing only to look good and take the best designer drugs. Ella, the film’s most significant female presence, remains an emotional traitor who betrayed Jonathan by leaving him. While some (particularly women) will automatically write this off as misogynistic (and it certainly is), one need only attend any celebrity party to see beautiful cosmetically enhanced women too willing to trade themselves off to the highest bidder for money, fame and quality heroin. The film rightfully debunks the ridiculous notion of sexual equality without even knowing it. Even Jonathan himself, a relatively sympathetic character who really does love his wife, treats women as disposable, first sending his lover Mackie (Pamela Hensley) packing near the beginning of the film, and later slipping her replacement Daphne (Barbara Trentham) aphrodisiacs to keep her quiet. The performances in the film are rather mediocre with one major exception.

While James Caan‘s brooding monotone serves his terminally depressed character well, and John Beck‘s twangy sidekick Moonpie provides the requisite humour, it’s John Houseman‘s portrayal of Bartholomew which instantly raises the movie above borderline pulp, through his malevolent performance as a subdued pill-popping megalomaniac with a finger on every button. As he sits enjoying his quiet-time in an office filled with razor-sharp wind-chimes designed to draw blood from all who enter, one can only imagine what must go through the head of a man who makes such decisions. Every time his mannered voice spouts another corporate truism, the film reaches a new level. Unfortunately, unless one takes the genre elements contained within the story seriously as an end unto themselves, not much remains to hold the attention of a mainstream audience between Rollerball games.

When a short story idea is stretched out to fill over two hours of screen time, the end result often involves a lot of padding and fake profundity. Jonathan’s desire to discover the hows and whys of corporate decision-making remains a non-mystery throughout the film, and generates very little tension. It’s as if the filmmakers assumed everyone had already read Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four, implicitly understanding exactly why book-censoring violence-sanctioning totalitarian societies are a bad thing. By the end of the film, Jonathan hasn’t learned much except, no matter what, he still loves to play Rollerball, even if it kills him. The Rollerball sequences are well-staged and exciting but off the track the film is slow and boring, consisting mainly of watching James Caan brood about what it all means. As science fiction the film is ultimately unsatisfactory because we are told very little about this future world of 2018, apart from the fact that corporations have abolished all individual nations and that war, poverty and disease no longer exist.

As a result the events in the film are left suspended in a cultural and social limbo, yet Jewison’s intention was to issue a warning about the growing violence in popular sports and how this caters to the baser instincts, but audiences so loved the action of the game that there was actually talk about forming rollerball leagues in the wake of the film, which downright horrified the director. Despite its shortcomings, Rollerball remains a significant moment in the history of genre cinema, richly evocative of an all-too-possible retro-future world. While other films like The Tenth Victim (1965), The Gladiators (1969), Death Race 2000 (1975), Turkey Shoot (1982), The Running Man (1987), Robot Jox (1990) and The Hunger Games (2012) franchise cover much of the same territory, Rollerball’s studio-sized budget and top-shelf talent invest the film with a credibility the others lack. Also, the passage of four decades gives the film not only an added charm but also an interesting subtext that is more relevant today than when it was first released.

Bartholomew states: “Corporate society was an inevitable destiny. A material dreamworld. Everything man touched became attainable.” Jonathan replies: “I’ve been touched all my life – caressed or hit – don’t seem to matter much anymore.” One need look no further than recent mergers of ever-larger media conglomerates or the suffocating advertising touting new devices and operating systems to comprehend we are all (perhaps irrevocably) immersed within the binding confines of corporate society. Whether it be a caress or a blow, judging from the daily bombardment of television talk shows describing the banal atrocities neighbours and friends inflict against one another, the future postulated in Rollerball isn’t scary enough. It’s about what people want, what people demand from each other, and sometimes they demand blood. In today’s society, as in the film’s apocalyptic final Rollerball game, there is no time limit, no substitutions, and everyone is a player until they die. What better implications can one ask of a classic science fiction film?

Director John McTiernan was declared the new hope for action movies in the eighties, and struck gold with the double-whammy of Predator (1987) and Die Hard (1988), ranking alongside The Terminator (1984) as the best action films of the decade. After the rousing thrills of The Hunt For Red October (1990) and the too-clever-for-its-own-good Last Action Hero (1993), it has been a long, slippery downhill journey for McTiernan. Medicine Man (1992), The Thirteenth Warrior (1999), The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) and Rollerball (2002), his sorry remake of the seventies original starring Chris Klein as Jonathan Cross. It was panned by critics and flopped at the box-office, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll ask you to please join me next week with your morbid curiosity well-prepared for another step beyond the inner limits of the outer sanctum with a touch of evil from the amazing zone known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Rollerball (1975)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews