SYNOPSIS:

John Harrington and his wife, Mildred, run an exclusive salon devoted to wedding apparel for women. Although he seems a harmless fashion designer, John is actually a serial killer, doing in his young customers on their wedding nights. With each murder, John is able to see a bit more of the long-repressed memory of his mother’s death. When he murders his wife, she returns to haunt him.

REVIEW:

Filmmaker extraordinaire Mario Bava changed the face of Italian cinema in 1963 when he crafted what is generally credited as the first giallo, The Girl Who Knew Too Much (also known as The Evil Eye). The subgenre would not only further Bava’s already-impressive success but also launch the careers of Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci, among others, not to mention its later impact on the American slasher.

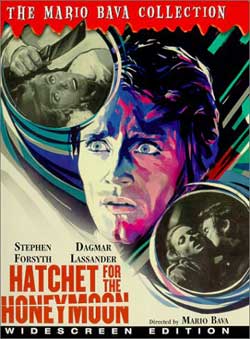

Bava helmed numerous gialli throughout his storied career, but an interesting point came in 1970, when Bava released not one but two films in the subgenre – Five Dolls for an August Moon and Hatchet for the Honeymoon. Both are classified as giallo films, but neither fully adheres to the structure he created. While the former fits at least some of the subgenre’s framework, Hatchet for the Honeymoon is a bit more difficult to classify.

The picture immediately forgoes a giallo staple: the whodunit mystery. As he reveals to viewers in a voiceover following the opening scene, John Harrington (Stephen Forsyth) is a paranoiac. Although he says the enchanting word is “so civilized, full of possibilities,” he confesses that he is completely mad. No one suspects that the 30-year-old bridal shop owner is a deadly madman, but he has already killed multiple brides prior to the events in the movie.

Since we already know who the killer is, the film explores why he is driven him to murder. John’s tendencies stems from his mother’s death, more of which is revealed with each kill. To add to his stress, John is trapped in a loveless marriage with his spiteful wife, Mildred (Laura Betti), who refuses to divorce him. Complicating things further, John also has a police inspector, Russell (Jesús Puente), hot on his trail, and a model, Helen (Dagmar Lassander), after his riches.

Hatchet for the Honeymoon fails to live up to the explicit title. (The translation of its Italian title, The Red Sign of Madness, is much more appropriate.) Despite being about a serial killer, it’s tame in terms of violence. The plot, frankly, is messy at best and dull at worst. It begins as a horror movie, following a twisted killer; then in shifts gears into the paranormal realm, when John is haunted by his wife whom he murdered (it’s no surprise to learn that the character was written into the script after Betti showed interest in a leading role); and lastly, it concludes in the fashion of a thriller.

What Hatchet for the Honeymoon lacks in storyline, however, it makes up for in visuals. Quite likely an influence on Dario Argento, the movie possesses a dreamlike quality. Bava uses his experimental cinematography to convey John’s mental instability. There are many camera zooms, often on actors’ eyes; a technique that can be tacky, but Bava has a way of making it elegant. The film also shares a surprising amount in common with American Psycho. Much like Patrick Bateman, John is a cunning playboy whose mask of sanity slowly slips away. Meanwhile, those around him remain oblivious to his dark secret. The two characters even share a penchant for black humor and inner monologues.

Hatchet for the Honeymoon has been remastered in high definition from an archival 35 mm print, now available from Kino Lober’s Redemption Films. It doesn’t seem to have been polished much; the audio pops and crackles at times, while the video has imperfections here and there. The transfer is perfectly watchable – better than it has ever looked – but it’s not great. Unfortunately, the Mario Bava: Maestro of the Macabre documentary found on the previous Anchor Bay release is absent, but there is an audio commentary by Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark author Tim Lucas. Much like on his Black Sunday track, he is knowledgeable about all things Bava.

There’s a reason Hatchet for the Honeymoon is not brought up as a top-tier effort in Bava’s filmography: he has many greatly superior works. That’s not to say that it’s not a good movie, but rather misunderstood. Bava has said that it’s his most personal film, and it’s also among his most ambitious (in a career full of ambition). While it doesn’t quite live up to his impressive canon, but Hatchet for the Honeymoon’s visual enticement alone warrants a watch.

Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews