SYNOPSIS:

“Scientist Andre Delambre becomes obsessed with his latest creation, a matter transporter. He has varying degrees of success with it. He eventually decides to use a human subject, himself, with tragic consequences. During the transference, his atoms become merged with a fly, which was accidentally let into the machine. He winds up with the fly’s head and one of it’s arms and the fly winds up with Andre’s head and arm. Eventually, Andre’s wife, Helene discovers his secret and must make a decision whether to let him continue to live like that or to do the unthinkable and euthanize him to end his suffering.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

During and after the Vietnam war, the image of our bodies as intensely vulnerable to decay and mutilation reached its climax (or its nadir) in the work of George Romero, David Cronenberg and others. Such imagery, however, did not just spring up out of no where. They were the wild children of an already existing family of images, a family with a history. The scientist whose work dreadfully deforms him in Tarantula (1955) is an early example of a long line of cinematic victims of technology, people who are rendered into monsters, whose bodies are changed or damaged, sometimes subtly, sometimes horribly. The saddest of all monsters is the one that was once just like you and me.

A woman whose husband undergoes an unpleasant change was also the subject of The Fly (1958) directed by Kurt Neumann, the prolific German-born filmmaker whose only other genre efforts were Rocketship XM (1950), She Devil (1957) and Kronos (1957). Despite an unusually absurd story, The Fly turned out to be the surprise box-office hit of the year, mainly because of the cunning approach adopted by Neumann, who also produced it. Instead of making another cheap exploitation movie, he shot the film in colour and hired a good cast and a competent scriptwriter – James Clavell adapted the original short story by George Langelaan that appeared in Playboy magazine the year before.

A woman whose husband undergoes an unpleasant change was also the subject of The Fly (1958) directed by Kurt Neumann, the prolific German-born filmmaker whose only other genre efforts were Rocketship XM (1950), She Devil (1957) and Kronos (1957). Despite an unusually absurd story, The Fly turned out to be the surprise box-office hit of the year, mainly because of the cunning approach adopted by Neumann, who also produced it. Instead of making another cheap exploitation movie, he shot the film in colour and hired a good cast and a competent scriptwriter – James Clavell adapted the original short story by George Langelaan that appeared in Playboy magazine the year before.

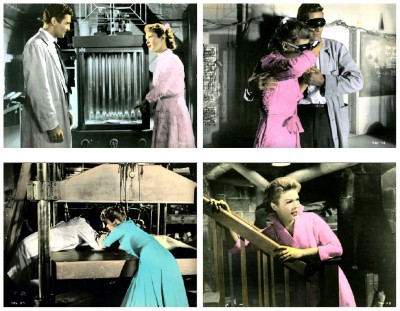

Neumann also insisted that the cast play it absolutely straight, although it must have been difficult at times as my old friend Vincent Price has his usual problem keeping his tongue out of his cheek. Patricia Owens plays Helene who, at the start of the film, has been arrested for crushing her husband’s head to a pulp in a giant steam press. In flashback we learn that the events that led her to take this extreme action. It seems that the husband Andre was a scientist experimenting with a matter transmitter in the basement of their house and, one day, had a nasty accident (Al Hedison – who later changed his name to David Hedison – plays Andre as Michael Rennie had dropped out after he discovered that he’d spend much of the film with his face covered).

Neumann also insisted that the cast play it absolutely straight, although it must have been difficult at times as my old friend Vincent Price has his usual problem keeping his tongue out of his cheek. Patricia Owens plays Helene who, at the start of the film, has been arrested for crushing her husband’s head to a pulp in a giant steam press. In flashback we learn that the events that led her to take this extreme action. It seems that the husband Andre was a scientist experimenting with a matter transmitter in the basement of their house and, one day, had a nasty accident (Al Hedison – who later changed his name to David Hedison – plays Andre as Michael Rennie had dropped out after he discovered that he’d spend much of the film with his face covered).

Helene starts suspecting something is wrong when he refuses to come out of the basement and starts asking for bowls of milk laced with rum to be left outside the door. When she finally persuades him to let her in, he greets her by draping a hood over his head and then, via a series of notes, instructs her to track down a certain fly that’s loose in the house, a fly with curious white markings. We discover that during an experiment, Andre had become mixed up with an ordinary house-fly which had got into one of the matter transmitter cabinets. The result is that he now has the head and arm of a fly, while the fly has his head and arm. The scene in which Helene pulls off Andre’s hood and sees his fly head – and he sees numerous images of her screaming face – is quite shocking, certainly one of the greatest moments in horror cinema. This worked primarily because actress Patricia Owens had a real fear of insects, and Neumann used this by not allowing her to see the makeup until the unmasking scene. Director Ridley Scott achieved a similar effect with the chest-burster scene in Alien (1979) by not warning the other actors involved that John Hurt’s chest was about to explode.

Unfortunately, many of the movie’s moments have not aged so well, like when Helene orders her small son Philippe (Charles Herbert) and housekeeper (Kathleen Freeman) to search the house and garden for the fly so her husband can reverse the experiment. We see lots of close-ups of flies, people swat flies only to hear Helene hysterically shout at them “I said catch them, not crush them!” At the end of the film, after Helene has done the right thing by crushing her husband in a steam press, we see a close-up of a fly caught in a web, complete with tiny human head and arm, squealing “Help me! Help me!” The police inspector in charge of the case promptly picks up a rock and crushes the evidence that would save Helene. But how is it that Andre still seemed to have his brain within the fly’s head firmly established upon his shoulders? What happened to the fly’s brain? Why do the doctors who performed the autopsy on the full-size body fail to detect that the crushed parts belonged to a large fly?

Unfortunately, many of the movie’s moments have not aged so well, like when Helene orders her small son Philippe (Charles Herbert) and housekeeper (Kathleen Freeman) to search the house and garden for the fly so her husband can reverse the experiment. We see lots of close-ups of flies, people swat flies only to hear Helene hysterically shout at them “I said catch them, not crush them!” At the end of the film, after Helene has done the right thing by crushing her husband in a steam press, we see a close-up of a fly caught in a web, complete with tiny human head and arm, squealing “Help me! Help me!” The police inspector in charge of the case promptly picks up a rock and crushes the evidence that would save Helene. But how is it that Andre still seemed to have his brain within the fly’s head firmly established upon his shoulders? What happened to the fly’s brain? Why do the doctors who performed the autopsy on the full-size body fail to detect that the crushed parts belonged to a large fly?

Possibly the most interesting element of the film is that this is one scientist-treading-where-no-man-should-tread movie in which the emphasis is placed on the wife of the scientist as she endures tragedy and tries everything in her power to save her husband. Although it shouldn’t be taken too seriously, The Fly is actually a feminist film in that a hapless wife becomes extremely capable – even though she understandably screams – when her husband, in a unique way, becomes handicapped and confined to his lab. Special credit must also be given to the film’s attempt at maintaining a realistically scientific atmosphere. When Vincent Price asks Helene what scientific breakthrough Andre has been working on, he actually suggests Flatscreen Television, one of the earliest mentions of such technology in cinema. The laboratory set cost only US$28,000 and included some surplus military equipment, and part of the set was Emerac, the computer from the 20th Century Fox production of Desk Set (1957).

Possibly the most interesting element of the film is that this is one scientist-treading-where-no-man-should-tread movie in which the emphasis is placed on the wife of the scientist as she endures tragedy and tries everything in her power to save her husband. Although it shouldn’t be taken too seriously, The Fly is actually a feminist film in that a hapless wife becomes extremely capable – even though she understandably screams – when her husband, in a unique way, becomes handicapped and confined to his lab. Special credit must also be given to the film’s attempt at maintaining a realistically scientific atmosphere. When Vincent Price asks Helene what scientific breakthrough Andre has been working on, he actually suggests Flatscreen Television, one of the earliest mentions of such technology in cinema. The laboratory set cost only US$28,000 and included some surplus military equipment, and part of the set was Emerac, the computer from the 20th Century Fox production of Desk Set (1957).

The Fly became the biggest box-office hit for director Neumann and his most influential film but, sadly, he never knew it. He died a month after the premiere of the film, and only a week before it went into general release. The film had spawned two less-than-mediocre sequels – Return Of The Fly (1959) and Curse Of The Fly (1965) – as well as an excellent re-imagining of The Fly (1986) on a genetic level directed by David Cronenberg, which spawned its own sequel imaginatively titled The Fly II (1989). It has also been thoroughly referenced in popular culture, from the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and The Simpsons to Beetlejuice (1988) and The Emperor’s New Groove (2000). The Fly was also the principal inspiration for ‘Mant!’ the movie-within-a-movie in Joe Dante’s wonderful homage to fifties exploitation films, Matinee (1993). And it’s with that recommendation in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

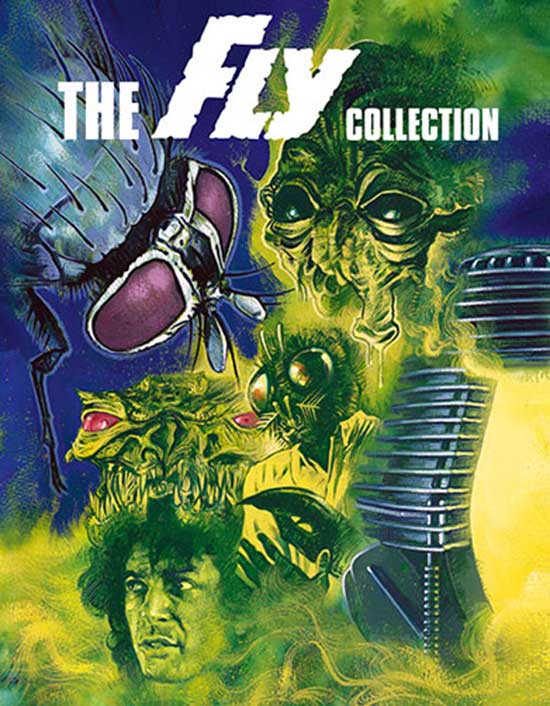

The Fly (1958) is now available on blu ray per THE FLY COLLECTION from Shout Factory

Bonus Features

DISC ONE: THE FLY (1958)

- NEW Audio Commentary With Author/Film Historian Steve Haberman And Filmmaker/Film Historian Constantine Nasr

- Audio Commentary With Actor David Hedison And Film Historian David Del Valle

- Biography: Vincent Price

- Fly Trap: Catching A Classic

- Fox Movietone News

- Theatrical Trailer

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews