SYNOPSIS:

“Darryl Revok is the most powerful of all the scanners, and is the head of the underground scanner movement for world domination. Scanners have great psychic power, strong enough to control minds, and can inflict enormous pain and damage on their victims. Doctor Paul Ruth finds a scanner that Revok hasn’t, and converts him to their cause – to destroy the underground movement.”

REVIEW:

David Cronenberg‘s films cover many different genres, from science fiction and horror to drama and thriller, and his films often mix genres with an originality that has changed the traditional understanding of film genres. Born in Canada, Cronenberg directed his first feature film Shivers (1975), but his biggest box-office hit without a doubt would be the re-imagining of The Fly (1986) which gave him the freedom to make such provocative films as Naked Lunch (1991) and Crash (1996). His films often include recurrent themes of disease, sex, and science gone awry. A principal figure of underground cinema, Cronenberg has been called the master of gross-out films because of the graphic display of violence or just plain disgusting subject matter. He has also achieved mainstream success more recent efforts like A History Of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007) and Cosmopolis (2012).

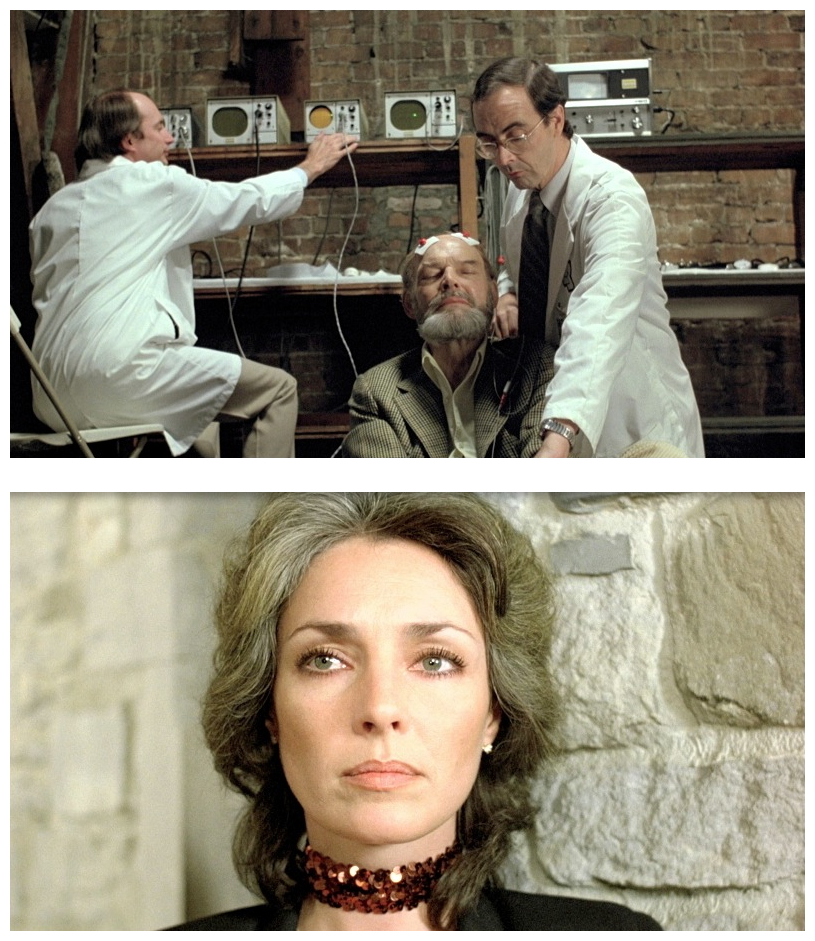

Inspired by a William S. Burroughs story about a hostile organisation of telepaths called ‘Senders’ bent on world domination, Scanners (1981) is, first and foremost, known to most as the exploding head movie, cinema’s most impressive moment of brain splatter. Ten minutes into the story, a battle of minds between two adversaries ends with the head of one of them blasting off its torso (it was originally released with the shocking scene at the very beginning of the film, but Cronenberg re-edited it, pushing the scene back a reel, specifically for latecomers). The forty-seven frames of gushing gore contained in that one masterful shot – composed by leading special effects wizards Dick Smith, Gary Zeller and Chris Walas – became an invitation to audiences to experiment with a new gadget: The video remote control. It’s the kind of scene where you say, “Yuck!” and then play it again in slow-motion a half-dozen times. The effect was accomplished by filling a latex head of the actor (Louis Del Grande) with dog food, leftover lunch, fake blood and rabbit livers, and shooting it from behind with a 12-gauge shotgun.

The exploding head shot in itself should make Scanners memorable, but there is more to the film than just a radical cure for migraine. Coming at a time when conspiracy thrillers were popular – Telefon (1977), Coma (1978), Capricorn One (1978) – Scanners exemplifies ultimate suspicion. No government, no drug, no-one can be trusted, or maybe it’s all in your head. In the case of Scanners, this is to be taken literally. The story revolves around 237 ‘scanners’ who were created as a result of an experimental tranquiliser given to pregnant women back in the forties. The women gave birth to children who grew up to have extraordinary powers, the ability to read thoughts, mentally control people, and cause heads to explode. There are good scanners and bad scanners, with the latter having the power to cause enough intense cerebral pressure to blow the head right off their victim’s shoulders.

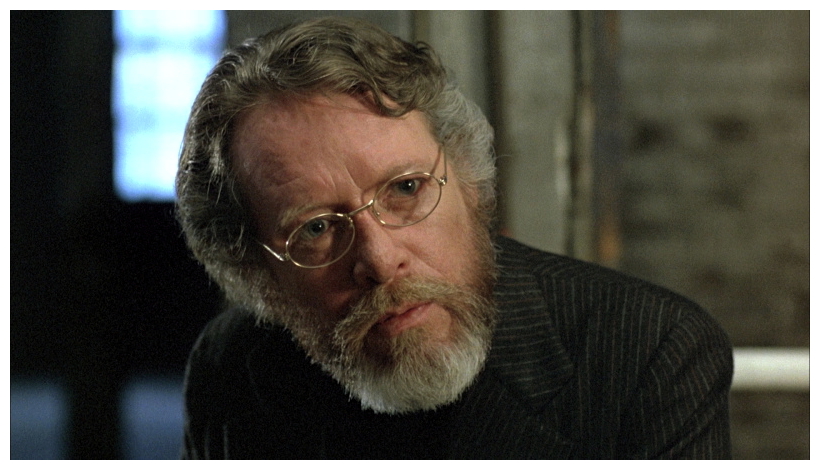

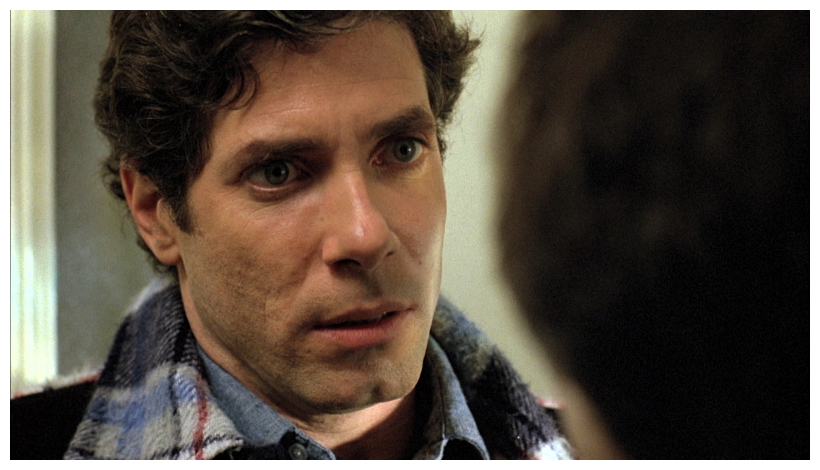

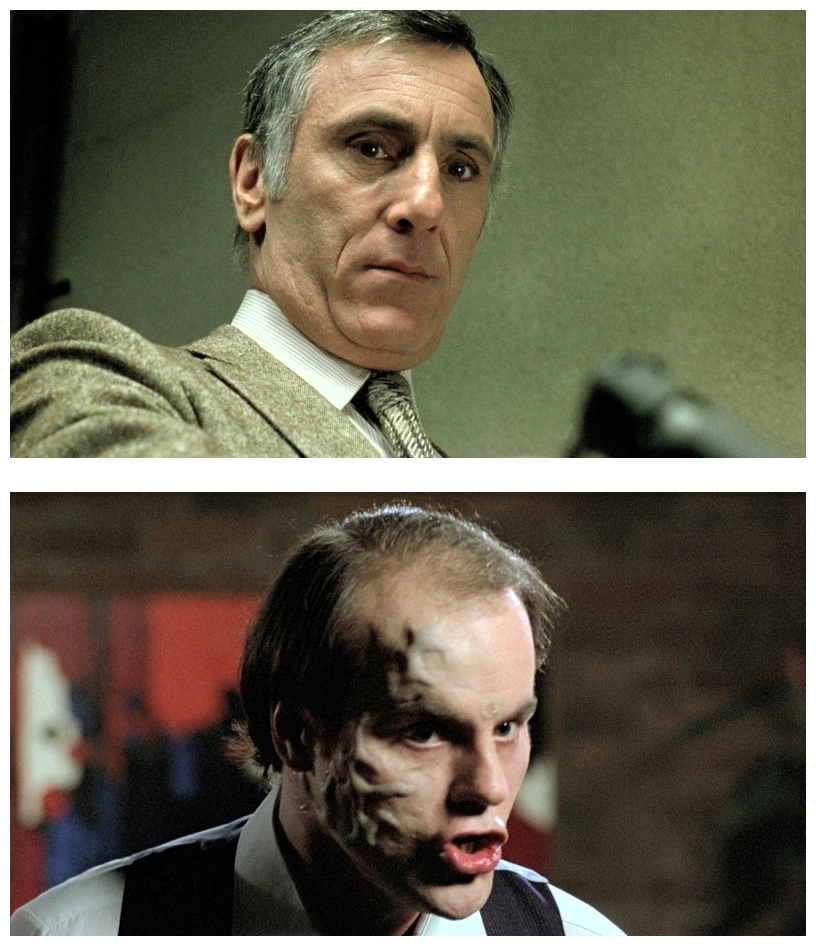

Doctor Paul Ruth (Patrick McGoohan), who invented the drug, recruits scanner Cameron Vale (Stephen Lack) to halt the nefarious activities of scanner Darryl Revok (Michael Ironside), who intends to turn the world’s population into a super-race of scanners. Vale finds himself in the middle of a civil war between the evil Revok’s scanner army and some decent scanners whom Revok is trying to wipe out. Vale eventually confronts Revok in a battle of wills that literally sparks fireworks and the loser gets the worst headache ever. Dick Smith did the amazing makeup effects for the climax as well and, when Revok is set on fire, Ironside is wearing a pair of fake eyes once worn by Dustin Hoffman in Little Big Man (1970). Spectacular stunt work and special effects aside, the film’s real power lies in its overall atmosphere of paranoia and desolation. The film’s urban guerrilla warfare scenes are far more enjoyable than watching heads exploding or eyes popping.

Much of this atmosphere is achieved through a mature treatment of the story, with explicit horror, violence, abuse and a constant blurring of the boundaries between good and evil. It gave Scanners an edgy militant look, one that stood in stark contrast to the other-worldly science fiction of Star Wars and Star Trek. Whether it was because of this militancy, or the exploding head, or because of a shooting at one of the first screenings of the film, Scanners became a surprise box-office success. Its subsequent video release was equally profitable and led to a number of sequels and a cult reputation – all evidence of its enduring appeal. Four sequels were released, none of which involved Cronenberg beyond the creation of original characters and concept.

Scanners II: The New Order (1991) was an effective sequel in which corrupt police chief John Forrester (Yvan Ponton) attempts to use scanners for his own ends, resulting in several exploding heads, and Scanners III: The Takeover (1992) is a technically slick but ultimately mindless movie about a scanner named Helena Monet (Liliana Komorowska) who is turned into a power-hungry killer by an experimental drug. The intriguing notion of the first film has become an excuse for a mediocre horror movie indistinguishable from (and no more distinguished than) a hundred others. Then there was Scanner Cop (1994) and Scanner Cop II: The Showdown (1995) which, needless to say, were simple cop shows about rookie police officer Sam Staziak (Daniel Quinn) who also happens to be a scanner. Just when it looked like a television series was going into production, the franchise was dropped like a hot rock and never heard from again. In 2007 director Darren Lynn Bousman announced a remake and hired David S. Goyer to write the script, but the project was shelved indefinitely due to Cronenberg’s refusal to participate.

According to Cronenberg, Scanners was the most frustrating film he ever made. Rushed through production, shooting had to begin without a complete script and had to wrap within two months so the financing would qualify as a tax write-off, forcing the director to write and shoot at the same time. He also had problems with actors McGoohan and O’Neill, who refused to get along with each other (this might explain why O’Neill doesn’t appear until 37 minutes into the film, despite receiving top billing as Kim Obrist, a member of Ruth’s guerrilla group). But there’s no doubt Cronenberg is proud of his mini-masterpiece, which touches on many different issues (multi-national pharmaceuticals, links between madness and art, sibling rivalry, parallels with thalidomide, etc.) without the messages getting in the way of the action or the horror. The fictional drug ephemerol bears an eerie similarity to the real-life scandal in the late fifties as women who had taken thalidomide during pregnancy (marketed as relief for morning sickness) sadly gave birth to children suffering phocomelia or other physical deformities.

Indeed, there is much here to recommend. Music by Howard Shore, cinematography by Mark Irwin, and excellent performances from both Patrick McGoohan (creator and star of the cult television series The Prisoner) and Michael Ironside (one of cinema’s best ever bad guys). Unfortunately, Stephen Lack is not exactly the most appealing choice for the lead, but certainly adequate. He had a terrible first day on set: “There we were, the first day of Scanners and they had me get into this eighteen-wheel truck with four gearshift levers and have me drive into the shot. It was horrifying. I never drove such a thing and I was pretty disoriented. We were set up on a feeder road to the highway, and all the camera crew and staff were there, and some car on the highway slowed down to gawk, and a truck on the highway rammed them from behind. There was a death and sirens, and the whole crew jumped over the storm fence to help out. I was given a slight reprieve of an hour to figure out the gears.”

There’s also Adam Ludwig, Lawrence Dane, Charles Shamata, and Robert Silverman who plays the artist scanner Benjamin Pierce. A favourite of Cronenberg’s, Silverman can also be seen in Rabid (1977), The Brood (1979), Naked Lunch (1991) and eXistenZ (1999). The bottom line is Scanners may not be a complete success and might not appeal to everyone, but it’s still a damn fine example from one of cinema’s most original and disturbing talents. Please join me next week to discover if cinema has yielded up another work of substance, or a nonsensical bit of fluff, all in the name of…Horror News! Toodles!

Scanners (1981)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Scanners is a great film. When Cronenberg eschews pretentious art films like ‘Naked Lunch’ he ends up making lasting art. Definitely a unique voice in cinema.

Here’s one of my favourite Cronenberg quotes, from a 1983 BBC radio interview: “When people ask me ‘Why do you make horror films?’ I immediately have to go back to Aristotle and his theory of catharsis as being a justification for high tragedy, or even comedy. For me, horror films are films of confrontation, not films of escape at all but, in a horror film, one confronts things that you might not really want to cope with in your real life, in a kind of safe dreamlike way. But you will meet these things eventually – I’m talking about aging, death, separation. That’s the metaphorical level that horror films work on. All my films, I’m aware of it now, are very body-conscious because, for me, the body is really the source of horror in human beings. It is the body which ages and the body which dies. It really is very Cartesian of me, I suppose, because to me the mind-body split is the source of the mystery and also the horror, which I think ultimately we have to confront. You see people whose minds are perfectly together while their bodies begin to distort, begin to change, begin to age, begin to rot, whatever. That to me is horror – I don’t want to give my audience a chance to get too distanced. That’s why my films are very urban and very contemporary in their setting.” Pretty impressive for an ad-lib answer in a radio interview.

Very impressive. There’s truth in that quote and bravery and self-awareness as well. Having a philosophical theme as a backbone to build on adds strength and depth to everything he creates.

Once again Nigel does his subject matter justice.