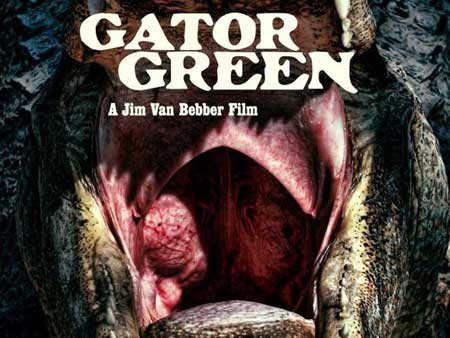

SYNOPSIS:

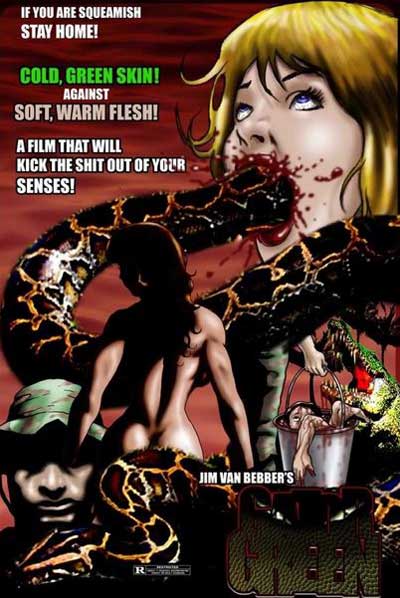

Florida, 1973. Vietnam vet Jack Andrew runs a bar with two of his Nam buddies. In the early hours of a Sunday morning Andrew snaps, and together with his cohorts terrorizes the patrons. He chops up the bartender and feeds the pieces to the hungry alligators nearby. When a drug dealer and his girlfriend arrive with a load of weed for the bartender in the morning, the trio victimizes them both. The dealer is torn apart alive by the gators, while the woman is tied up and shot to death.

REVIEW:

If the synopsis above seems bare or underdeveloped, it’s because Gator Green is a 16-minute short that was made with the purpose of raising funds for a feature. This is not an uncommon origin for many well-known films, in the horror genre or otherwise. But where many short films were later reshot and expanded into a feature, such as The Evil Dead or Saw, Gator Green is based on an excerpt from the middle of a feature-length script, and is actually intended to be incorporated into the final product.

Director Jim Van Bebber is no stranger to the difficulties of securing funds for a film. Like Gator Green, his earlier shorts Roadkill: The Last Days of John Martin (1994) and Chunk Blower (1990) were supposed to eventually take shape as feature films, but the former unfortunately remained an enticing sampler, while the latter saw the light of day as a trailer for a movie that never materialized. This foreshadows the recent trend of fake trailers that have been developed into popular neo-grindhouse crowd-pleasers, such as Machete or Hobo with a Shotgun, the genesis of both provided by Grindhouse (2007).

It was in the decade that killed off the grindhouse that Van Bebber started making a name for himself in the underground, with his kick-ass debut feature Deadbeat at Dawn (1988), an ultra-low-budget action/splatter film that took several years to complete. His only other feature to date, his controversial magnum opus The Manson Family, was started around the same time but wasn’t completed until 2003 – some fifteen years later. Gator Green screened with The Manson Family at its theatrical revival in 2013, and is featured on the 10th anniversary release of the film on disc.

While in its current truncated form Gator Green is understandably disjointed and unsatisfying, Van Bebber deserves credit for still being able to deliver stuff that drags the grindhouse kicking and screaming into the new millennium, without trying to capitalize on any trend – forget the studio-backed self-conscious homages of Robert Rodriguez or Rob Zombie. Shot in 16mm with bad sound, shoddy effects and sporadic incoherence, Gator Green is an unashamed throwback that feels closer to something like Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive (1977) than much of the current crop of neo-grindhouse.

With the theme of crazed, crippled Vietnam vets on the loose, shots of the Stars and Stripes, and footage of infamous war atrocities, you might think there is some personal or political statement at the root of the film. Nope. The director (and lead actor) himself has stated that while there is some political subtext, his film is “nasty and unapologetic and aspires to no social meaning.” What you see is what you get: hippie dealers, alligators devouring helpless victims, eight-tracks and overgrown ’70s bush, clumsy splatter, and an actor in blackface wearing a pink suit that looks like it came from Pimps’R’Us.

Gator Green pools some interesting talent around its legendary director. Special effects wizard Marcus Koch (100 Tears, Slow Torture Puke Chamber) makes yet another appearance, and producer Stephen Biro (head honcho of extreme/cult horror DVD label Unearthed Films) also has a small acting role. Van Bebber subsequently teamed up with both for American Guinea Pig: Bouquet of Guts and Gore, in which he made a brief appearance, in addition to his role as cinematographer. Many viewers (and headbangers) will otherwise know him from his collaboration with Necrophagia, Through Eyes of the Dead (2000). While Gator Green is far from the best place to start for those new to Jim Van Bebber, it’s good to know that he’s still leaving his grimy fingerprints on the ravaged body of exploitation cinema.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews