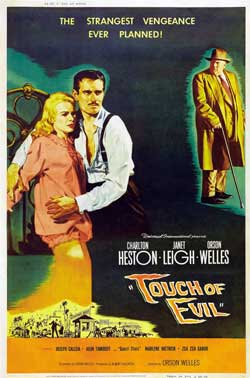

SYNOPSIS:

A stark, perverse story of murder, kidnapping, and police corruption in a Mexican border town.

REVIEW:

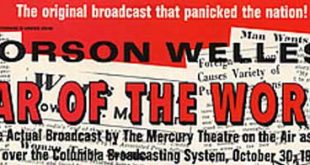

“This isn’t the real Mexico. You know that. All border towns bring out the worst in a country.”

A quintessential entry in the classic film noir genre, Orson Welles’ misanthropic thriller is not only one of his most polished films but one of the most influential and uncompromising pictures of the 20th century. Very loosely based on the 1956 novel, Badge of Evil, by Whit Masterson, Welles’ challenge was to direct a good film out of a bad screenplay (while having never read the novel). The result of his efforts, re-edited by Universal International was, upon its initial release, a commercial failure in the U.S. despite accolades by such innovative filmmakers as Francois Truffaut (400 Blows, Jules and Jim, Shoot the Piano Player), Peter Bogdanovich (Last Picture Show, Paper Moon, Targets), Brian DePalma (Scarface, Sisters, Phantom of the Paradise), and Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless, Contempt, Week End, Alphaville, Vivre sa Vie). Today, its baroque individualism and moral conundrums fare well, as does Welles’ inimitably grotesque style and the darkly satirical screenplay.

Charlton Heston is drug enforcement official, Miguel Vargas, who becomes embroiled in a ring of corruption and debauchery. The film opens with a historically-virtuosic, unbroken tracking shot totaling over three minutes: Vargas and his wife, Susan (Janet Leigh), are strolling down a city street when a car is driven over the U.S.-Mexico border and explodes – the result of a car bomb planted only moments before on Mexican soil. In the restored version, this scene is groundbreaking not only in its effective use of incidental music as characters walk down a busy street in the fictional Mexican town of Los Robles (where cabaret orchestras fade in and out of earshot) but in the sheer amount of choreography involved in its execution. The audience is thus immediately immersed in Welles’ Kafkaesque world filled with nauseating close-ups and sardonic tones, looming shadows and seedy locales.

The Police Chief, District Attorney, and corrupt police captain, Hank Quinlan (played by Welles, wearing a fake nose and padded clothing to make his frame look bigger) soon become involved in the incident. Quinlan, an alcoholic whose narcissistic marque of justice leads more towards venality than integrity, is Vargas’ antagonist but also his proverbial twin.

The duality lies in their objective; where they differ is method. Vargas is a self-righteous puritan and in many ways an idealist, lobbying for equality and moral rectitude. Quinlan is a disillusioned flouter not above planting evidence or falsifying information to secure a conviction. And it isn’t long before Quinlan begins acting on a hunch, interrogating a young Mexican man by the name of Sanchez for the crime. However, with no evidence to support his theory, he plants dynamite in the suspect’s apartment. Vargas knows the evidence was planted and begins his own investigation. Later, there are moments of sheer horror, especially for Susan Vargas, as she is dropped off at a motel by her husband as he grapples with his investigation of Quinlan’s agenda-driven conclusions. It is in this juxtaposition of plot that Susan is framed by Quinlan’s associates as a junkie in an attempt to discredit Vargas.

Quinlan is a most interesting character. Tanya, a fortune teller played by Marlene Dietrich, tells the captain, “Your future’s all used up.” She is telling his fortune even as she refuses him. Quinlan’s future, as described by Tanya, is also an ironic premonition into Welles’ own cinematic career in that he would never direct another picture within the Hollywood system again. Later, Tanya says of Quinlan, “He was some kind of man … what does it matter what you say about people?” His wife was strangled by an anonymous killer in some unspecified incident in the past (“That was the last killer that ever got out of my hands”); he is a man who once attempted to battle his demons and lost. His sense of justice is now a distorted delusion of righteousness, fervently condemning criminals yet dismissive of the crimes he enacts to convict them. His partner, Pete Menzies, tells him, “You’re a killer,” to which Quinlan replies, “Partly. I’m a cop.” His instinct is impeccable, but ethically he is bankrupt.

The cinematography is flamboyantly vivid where every scene, with a remainder of the preceding, filters into the next with sheer fluidity. It was Welles’ way to entangle every character together in typical Kafkaesque fashion where there is only a lateral progression, of characters trapped within destinies of their own making and doomed to repeat them.

Rating: A+

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews