SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Louis Mazzini’s mother’s frequent tales of how her titled D’Ascoyne family shunned her after she eloped with an Italian commoner causes a simmering resentment in him. On being spurned because of his lowly status by his lifetime (if devious and fickle) sweetheart Sibella he decides to permanently remove all the D’Ascoynes standing between him and the Dukedom. Becoming romantically involved with one of the widows he has created, he finds Sibella’s jealousy could seriously threaten his grand design.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

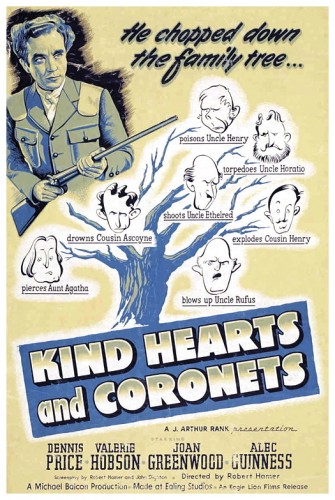

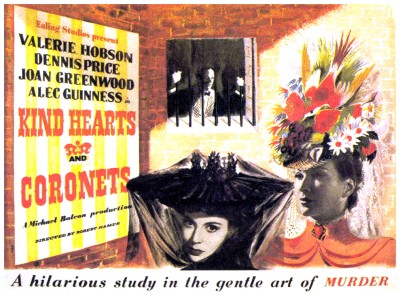

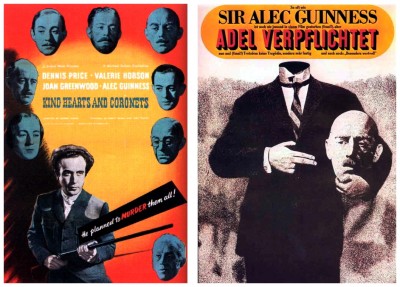

It may not be the greatest British comedy ever made, but it comes close. It’s certainly one of the finest of many quintessential English comedies produced by Michael Balcon at Ealing Studios. Kind Hearts And Coronets (1949) has all the elements of British humour: class warfare; a sense of history; a sardonic black edge; shady glamour; and the adornment of eccentricity. Sex, greed and murder lie at the heart of the movie, always good story-driving plot-lines, but here they are presented with a sly charm that places the viewer on the side of the serial killer rather than his victims. The scenario is, in fact, a classic whodunnit story turned upside-down. From the beginning we know ‘whodunit’ as the disinherited but aspiring Louis Mazzini (Dennis Price), a drapery clerk, takes us into his confidence in his prison cell awaiting execution.

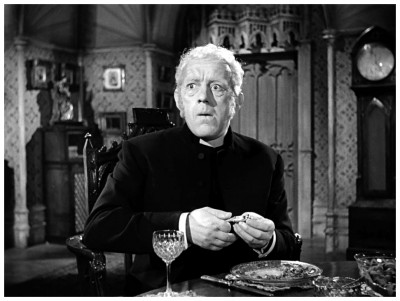

In a series of elaborate flashbacks, he recounts his disposal of the senior members of the aristocratic D’Ascoyne family that stood between him and the Dukedom of Chalfont. It is his way of avenging his mother, a noblewoman by birth who was ostracized from the family, fell into a life of hard labour and was denied a place in the family plot because she had married beneath her class. The fact that all his victims are played by Alec Guinness only adds to the fun. Although he plays eight members of the D’Ascoyne family, Mazzini only kills six of them (Lord Ascoyne D’Ascoyne, the banker, dies of shock when he hears of the ‘accidental’ death of Ethelred D’Ascoyne while hunting) but Mazzini is condemned, ironically, for the one murder he did not commit.

In a series of elaborate flashbacks, he recounts his disposal of the senior members of the aristocratic D’Ascoyne family that stood between him and the Dukedom of Chalfont. It is his way of avenging his mother, a noblewoman by birth who was ostracized from the family, fell into a life of hard labour and was denied a place in the family plot because she had married beneath her class. The fact that all his victims are played by Alec Guinness only adds to the fun. Although he plays eight members of the D’Ascoyne family, Mazzini only kills six of them (Lord Ascoyne D’Ascoyne, the banker, dies of shock when he hears of the ‘accidental’ death of Ethelred D’Ascoyne while hunting) but Mazzini is condemned, ironically, for the one murder he did not commit.

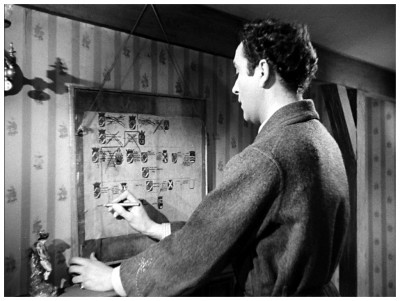

Our ‘hero’ is a complete cad. Along his murderous way, Mazzini seduces both Edith D’Ascoyne (Valerie Hobson) and Sibella (Joan Greenwood) who are competing for his attentions, but Mazzini is so disarmingly indifferent that we forget that we are in the presence – indeed the mind – of a cold-hearted serial killer. We laugh as each person is killed, even though Mazzini’s methods are cruel and only a couple of the victims seem like they really deserve such punishment. As Mazzini gets closer to his title, he becomes increasingly like the arrogant aristocrats he despises. As his narration reflects, he always had the heart and mind of a lord – he speaks of the ‘humiliating’ work his mother endures, and we see her gently polishing a shoe – and, if anything, he regards himself as superior to all of humanity, which corresponds to the Nietzschean aspects of the original novel.

Our ‘hero’ is a complete cad. Along his murderous way, Mazzini seduces both Edith D’Ascoyne (Valerie Hobson) and Sibella (Joan Greenwood) who are competing for his attentions, but Mazzini is so disarmingly indifferent that we forget that we are in the presence – indeed the mind – of a cold-hearted serial killer. We laugh as each person is killed, even though Mazzini’s methods are cruel and only a couple of the victims seem like they really deserve such punishment. As Mazzini gets closer to his title, he becomes increasingly like the arrogant aristocrats he despises. As his narration reflects, he always had the heart and mind of a lord – he speaks of the ‘humiliating’ work his mother endures, and we see her gently polishing a shoe – and, if anything, he regards himself as superior to all of humanity, which corresponds to the Nietzschean aspects of the original novel.

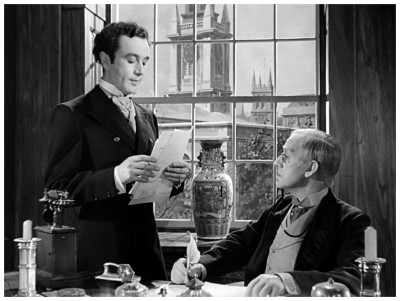

I suppose that what makes his murders tolerable (and funny) is that Guinness conveniently plays all the victims. He was originally offered only four of the roles: “I read the screenplay on a beach in France, collapsed with laughter on the first page, and didn’t even bother to get to the end of the script. I went straight back to the hotel and sent a telegram saying, why four parts? Why not eight?” We are not shocked by each death because we correctly expect Guinness to turn up again quite soon. We also laugh because of the amorality of the whole piece, particularly Mazzini’s cold-blooded narration – it’s so unlike the British comedy of manners it resembles in tone but not content. It’s a beautifully played film with an absolutely exquisite script, the sophisticated dialogue is reminiscent of Oscar Wilde. Adding to the amusement is that while the educated characters engage in smart conversation, or Mazzini’s silver-tongued narration hints at his egocentricity, absolutely silly events occur: One victim blows up in the background, lovers plunge over a waterfall, etc.

I suppose that what makes his murders tolerable (and funny) is that Guinness conveniently plays all the victims. He was originally offered only four of the roles: “I read the screenplay on a beach in France, collapsed with laughter on the first page, and didn’t even bother to get to the end of the script. I went straight back to the hotel and sent a telegram saying, why four parts? Why not eight?” We are not shocked by each death because we correctly expect Guinness to turn up again quite soon. We also laugh because of the amorality of the whole piece, particularly Mazzini’s cold-blooded narration – it’s so unlike the British comedy of manners it resembles in tone but not content. It’s a beautifully played film with an absolutely exquisite script, the sophisticated dialogue is reminiscent of Oscar Wilde. Adding to the amusement is that while the educated characters engage in smart conversation, or Mazzini’s silver-tongued narration hints at his egocentricity, absolutely silly events occur: One victim blows up in the background, lovers plunge over a waterfall, etc.

My only complaint is an overly convenient (for the writers) ending that saves Mazzini from having to make difficult decisions. In the final seconds of the film, Mazzini is proven innocent and pardoned but, upon his release, he realises that he has, fatally, left his hand-written memoirs in his cell. The screenplay by John Dighton was based on the 1907 novel Israel Rank by Roy Horniman. The novel is definitely darker (including the murder of a child) and varies greatly from the finished film. One big difference was that the main character in the novel (Israel Rank) was half-Jewish rather than half-Italian, and his ruthless using of both men and women in his greedy pursuit of position all seem to conform to the stereotypical anti-Semite view of the Jew.

My only complaint is an overly convenient (for the writers) ending that saves Mazzini from having to make difficult decisions. In the final seconds of the film, Mazzini is proven innocent and pardoned but, upon his release, he realises that he has, fatally, left his hand-written memoirs in his cell. The screenplay by John Dighton was based on the 1907 novel Israel Rank by Roy Horniman. The novel is definitely darker (including the murder of a child) and varies greatly from the finished film. One big difference was that the main character in the novel (Israel Rank) was half-Jewish rather than half-Italian, and his ruthless using of both men and women in his greedy pursuit of position all seem to conform to the stereotypical anti-Semite view of the Jew.

The timing of the film hovers over the intersection between ‘old’ Britain and ‘new’ Britain – World War Two was over, a socialist government had been elected and the country was still in the grip of post-war austerity. Nineteenth-century British novelists like Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope and Wilkie Collins had enjoyed a huge revival during the second world war (especially among those serving on the front lines), and George Orwell‘s The Decline Of The English Murder published in 1946 added inspiration. The mixture of nostalgia for a ‘Great’ Britain and the eccentric characters who populate these novels is a theme that director Robert Hamer knowingly teases out. Hamer had made some similarly deft and dark films before Kind Hearts And Coronets, like the Haunted Mirror segment of Dead Of Night (1945), Pink String And Ceiling Wax (1945) and It Always Rains On Sunday (1946), but his later decline into alcoholism is one of the great losses to British cinema.

The timing of the film hovers over the intersection between ‘old’ Britain and ‘new’ Britain – World War Two was over, a socialist government had been elected and the country was still in the grip of post-war austerity. Nineteenth-century British novelists like Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope and Wilkie Collins had enjoyed a huge revival during the second world war (especially among those serving on the front lines), and George Orwell‘s The Decline Of The English Murder published in 1946 added inspiration. The mixture of nostalgia for a ‘Great’ Britain and the eccentric characters who populate these novels is a theme that director Robert Hamer knowingly teases out. Hamer had made some similarly deft and dark films before Kind Hearts And Coronets, like the Haunted Mirror segment of Dead Of Night (1945), Pink String And Ceiling Wax (1945) and It Always Rains On Sunday (1946), but his later decline into alcoholism is one of the great losses to British cinema.

Another great loss was actor Dennis Price, whose career had faded step-by-step into increasingly burlesque appearances in ever-cheaper horror films. In 1967, Price was declared bankrupt due to “Extravagant living and most inadequate gambling,” and towards the end of his life he could be spotted in Twins Of Evil (1971), Horror Hospital (1973), Theatre Of Blood (1973), and a truly star-studded version of Alice In Wonderland (1972) alongside Ralph Richardson, Peter Sellers, Robert Helpmann, Dudley Moore, Terry Thomas and many more. One of the most interesting people involved with the production of Kind Hearts And Coronets could only be found behind the camera – cinematographer Douglas Slocombe OBE. After cutting his industry teeth at Ealing Studios, he photographed more than eighty films in less than half a century before his retirement in 1989, including the original horror anthology film Dead Of Night (1945), The Man In The White Suit (1951), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953).

Another great loss was actor Dennis Price, whose career had faded step-by-step into increasingly burlesque appearances in ever-cheaper horror films. In 1967, Price was declared bankrupt due to “Extravagant living and most inadequate gambling,” and towards the end of his life he could be spotted in Twins Of Evil (1971), Horror Hospital (1973), Theatre Of Blood (1973), and a truly star-studded version of Alice In Wonderland (1972) alongside Ralph Richardson, Peter Sellers, Robert Helpmann, Dudley Moore, Terry Thomas and many more. One of the most interesting people involved with the production of Kind Hearts And Coronets could only be found behind the camera – cinematographer Douglas Slocombe OBE. After cutting his industry teeth at Ealing Studios, he photographed more than eighty films in less than half a century before his retirement in 1989, including the original horror anthology film Dead Of Night (1945), The Man In The White Suit (1951), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953).

Slocombe won the BAFTA Best Cinematography award for The Servant (1963), The Great Gatsby (1974) and Julia (1977), and was nominated for Guns At Batasi (1964), The Blue Max (1966), The Lion In Winter (1968), Travels With My Aunt (1973), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), Rollerball (1975), Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984) and Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989). He has also won the British Society Of Cinematographers award five times, and was finally presented with their Lifetime Achievement award in 1996. Despite this incredible body of work, he has only ever been nominated for three Oscars, winning none whatsoever. I’ll allow you to mull over the questionable judgment of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the next seven days, and ask you to please join me next week when I have another opportunity to force-feed you more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Slocombe won the BAFTA Best Cinematography award for The Servant (1963), The Great Gatsby (1974) and Julia (1977), and was nominated for Guns At Batasi (1964), The Blue Max (1966), The Lion In Winter (1968), Travels With My Aunt (1973), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), Rollerball (1975), Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984) and Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989). He has also won the British Society Of Cinematographers award five times, and was finally presented with their Lifetime Achievement award in 1996. Despite this incredible body of work, he has only ever been nominated for three Oscars, winning none whatsoever. I’ll allow you to mull over the questionable judgment of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the next seven days, and ask you to please join me next week when I have another opportunity to force-feed you more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews