SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Harry Powell marries and murders widows for their money, believing he is helping God do away with women who arouse men’s carnal instincts. Arrested for auto theft, he shares a cell with condemned killer Ben Harper and tries to get him to reveal the whereabouts of the $10,000 he stole. Only Ben’s nine-year-old son, John and four-year-old daughter, Pearl know the money is in Pearl’s doll and they have sworn to their father to keep this secret. After Ben is executed, Preacher goes to Cresap’s Landing to court Ben’s widow, Willa. He overwhelms her with his Scripture quoting, sermons and hymns, and she agrees to marry him. On their wedding night he tells her they will never have sex because it is sinful. When the depressed, confused, guilty woman catches him trying to force Pearl to reveal the whereabouts of the money, she is resigned to her fate but the children manage to escape downriver, with Preacher following close behind.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Cult movies need to be found or rediscovered, by the viewing public as much as by critics. The French magazine Cahiers Du Cinema (in print since 1951) promoted a new way of thinking about movies that dusted off many forgotten masterpieces. They brought the work of B-movie directors such as Nicholas Ray, Samuel Fuller and many others to a new audience. In doing so, they created the idea of cult cinema. Sometimes cult films may be simply enjoyably awful, such as Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959), or they may be vaguely worthy as interesting works hidden among the detritus of drive-in exploitation, such as the ‘educational’ film Reefer Madness (1936) or the downright bizarre Glen Or Glenda (1952). Cult movies cannot be created, although filmmakers such as Roger Corman, Russ Meyer, David Lynch, Jim Jarmusch, Alex Cox, Quentin Tarantino, John Waters and the Coen Brothers all play upon the eccentricity of their work in the cult market.

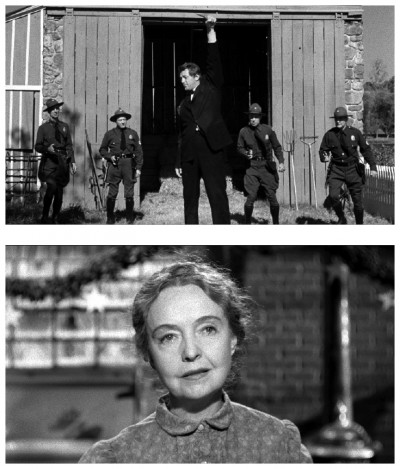

The Night Of The Hunter (1955) is a prime example of a cult movie. Beautifully crafted, it was largely ignored upon its release, but grew in critical stature over the next decade. The only film to be directed by British actor Charles Laughton, produced late in his career, is a chilling, expressionistic, childlike fantasy inspired by the silent films of D.W. Griffith, and stars Griffith’s favourite leading lady Lillian Gish. Adapted by James Agee from the novel by the eccentric Davis Grubb and strikingly photographed by Stanley Cortez, it is a fascinating, truly unique work, part Gothic horror film, part religious parable, part fairy-tale: Beware of a wolf in sheep’s clothing or, more precisely, a false prophet in preacher’s garb. Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) is a demented itinerant evangelist during the Depression who uses his tattooed fingers (HATE on one hand, LOVE on the other) to demonstrate his sermons. He also kills, he says, on behalf of the Lord.

The Night Of The Hunter (1955) is a prime example of a cult movie. Beautifully crafted, it was largely ignored upon its release, but grew in critical stature over the next decade. The only film to be directed by British actor Charles Laughton, produced late in his career, is a chilling, expressionistic, childlike fantasy inspired by the silent films of D.W. Griffith, and stars Griffith’s favourite leading lady Lillian Gish. Adapted by James Agee from the novel by the eccentric Davis Grubb and strikingly photographed by Stanley Cortez, it is a fascinating, truly unique work, part Gothic horror film, part religious parable, part fairy-tale: Beware of a wolf in sheep’s clothing or, more precisely, a false prophet in preacher’s garb. Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) is a demented itinerant evangelist during the Depression who uses his tattooed fingers (HATE on one hand, LOVE on the other) to demonstrate his sermons. He also kills, he says, on behalf of the Lord.

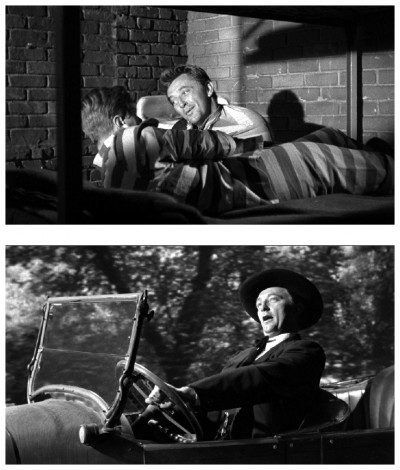

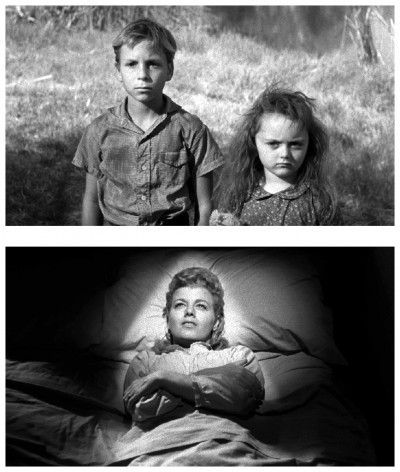

Powell has just been released from prison on a car-theft charge. While inside he meets Ben Harper (Peter Graves) on Death Row for an armed robbery, who boasts of his $10,000 haul from the job, but fails to reveal where he’s hidden it. Powell heads for Harper’s hometown, locates his widow (Shelley Winters) and convinces her to marry him. Unfortunately, she knows nothing about the loot so, in frustration, he stabs her to death. Her young son (Billy Chapin) – the only person who doesn’t trust the preacher – grabs the moneybag and his little sister (Sally June Bruce) and they flee, with the preacher following on horseback, intent on killing the children for the money. Most impressive is the haunting multi-plane shots when the canoe carrying the runaway children floats downstream.

Powell has just been released from prison on a car-theft charge. While inside he meets Ben Harper (Peter Graves) on Death Row for an armed robbery, who boasts of his $10,000 haul from the job, but fails to reveal where he’s hidden it. Powell heads for Harper’s hometown, locates his widow (Shelley Winters) and convinces her to marry him. Unfortunately, she knows nothing about the loot so, in frustration, he stabs her to death. Her young son (Billy Chapin) – the only person who doesn’t trust the preacher – grabs the moneybag and his little sister (Sally June Bruce) and they flee, with the preacher following on horseback, intent on killing the children for the money. Most impressive is the haunting multi-plane shots when the canoe carrying the runaway children floats downstream.

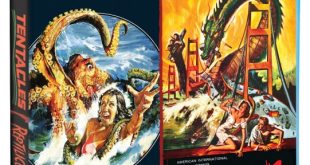

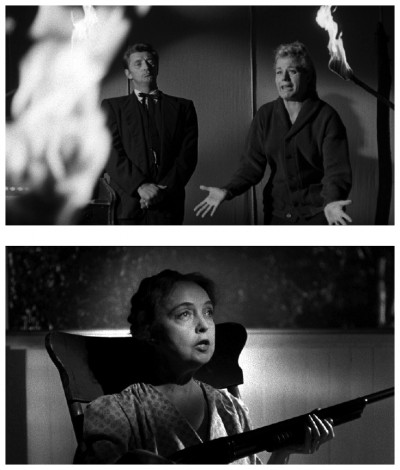

The children are like Hansel and Gretel traveling through the woods following the river, only to find a sweet old lady named Rachel (Lillian Gish), a truly Christian woman who takes in orphan children. When the preacher comes after the two children, she recognises him for the hypocrite he is. She is determined to protect the kids, even against this intimidating Devil figure. The strong-bodied preacher versus the strong-willed woman make great opponents, particularly when he sings the religious hymn Leaning On The Everlasting Arms while standing in the darkness and planning to strike, and she joins in, singing the correct words including a reference to Jesus.

The children are like Hansel and Gretel traveling through the woods following the river, only to find a sweet old lady named Rachel (Lillian Gish), a truly Christian woman who takes in orphan children. When the preacher comes after the two children, she recognises him for the hypocrite he is. She is determined to protect the kids, even against this intimidating Devil figure. The strong-bodied preacher versus the strong-willed woman make great opponents, particularly when he sings the religious hymn Leaning On The Everlasting Arms while standing in the darkness and planning to strike, and she joins in, singing the correct words including a reference to Jesus.

Laughton’s audacious visual style, borrowed from Griffith and German Expressionists, is almost too arty for an American film, but there are moments of amazing beauty. Everyone involved bought into Laughton’s idea (a nightmarish Mother Goose tale) to create a truly unique movie. There were many rumours and reports that screenwriter James Agee, very late in his career, was often drunk and couldn’t care less about this, his final film script ever. These rumours were laid to rest in 2004 when Agee’s first draft of the script was discovered. That document, although 293 pages in length, is scene-for-scene the film that Charles Laughton directed. Laughton, confronted with such a hugely overwritten script, simply renewed Agee’s contract and ordered him to cut it in half.

Laughton’s audacious visual style, borrowed from Griffith and German Expressionists, is almost too arty for an American film, but there are moments of amazing beauty. Everyone involved bought into Laughton’s idea (a nightmarish Mother Goose tale) to create a truly unique movie. There were many rumours and reports that screenwriter James Agee, very late in his career, was often drunk and couldn’t care less about this, his final film script ever. These rumours were laid to rest in 2004 when Agee’s first draft of the script was discovered. That document, although 293 pages in length, is scene-for-scene the film that Charles Laughton directed. Laughton, confronted with such a hugely overwritten script, simply renewed Agee’s contract and ordered him to cut it in half.

Robert Mitchum turns in a career-transforning performance of undiluted psychopathic evil, a role originally intended for my old friend and fellow thespian Sir Laurence Olivier. When Sir Larry became unavailable, Gary Cooper was offered the role, but he turned it down saying it would be detrimental to his career. Mitchum’s demonic performance as the demented preacher played against type, but proved he was an actor to be reckoned with. His unfortunate victim was also a career-making role for the amazingly beautiful Shelley Winters. For those viewers made uncomfortable by Mitchum’s violent interaction with the children on-screen, it is enough to know that the openly homosexual Laughton was even more uncomfortable directing child actors, so Mitchum tenderly directed most of these scenes himself.

Robert Mitchum turns in a career-transforning performance of undiluted psychopathic evil, a role originally intended for my old friend and fellow thespian Sir Laurence Olivier. When Sir Larry became unavailable, Gary Cooper was offered the role, but he turned it down saying it would be detrimental to his career. Mitchum’s demonic performance as the demented preacher played against type, but proved he was an actor to be reckoned with. His unfortunate victim was also a career-making role for the amazingly beautiful Shelley Winters. For those viewers made uncomfortable by Mitchum’s violent interaction with the children on-screen, it is enough to know that the openly homosexual Laughton was even more uncomfortable directing child actors, so Mitchum tenderly directed most of these scenes himself.

Unfortunately, distributors United Artists weren’t exactly sure how to market the film – it wasn’t a straightforward thriller but not exactly an art-house piece either. Upon its release, audiences found it simply too weird, and it flopped. Laughton was so disappointed by the poor critical and commercial reception of his film that he vowed never to direct again, and he never did. It’s with this sad thought in mind I’ll thank Simon Callow (author of the British Film Institute book on The Night Of The Hunter) for assisting my research for this article, and I’ll politely request your persistence…I mean, presence next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Unfortunately, distributors United Artists weren’t exactly sure how to market the film – it wasn’t a straightforward thriller but not exactly an art-house piece either. Upon its release, audiences found it simply too weird, and it flopped. Laughton was so disappointed by the poor critical and commercial reception of his film that he vowed never to direct again, and he never did. It’s with this sad thought in mind I’ll thank Simon Callow (author of the British Film Institute book on The Night Of The Hunter) for assisting my research for this article, and I’ll politely request your persistence…I mean, presence next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations to ever be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews