Hideshi, a typical salary man, is not having a good week. His beautiful girlfriend, Kyoko, is sleeping with a colleague, Nakamura, and his boss at the computer company where he works has been berating him for not doing a good job. He locks himself in his flat, and not even his boss bothers to ring him up to see if everything is alright. The solution seems simple, suicide, but as befits a Guinea Pig film, it is easier said than done, and despite slitting his wrists, strangling himself, cutting his throat and dismembering various body parts until he is just a disembodied head, Hideshi never dies.

REVIEW:

The third instalment in the notorious Guinea Pig series of films, He Never Dies is a great deal more fun than the previous two instalments – The Devil’s Experiment (Za Ginī Piggu: Akuma no Jikken: 1985) and Flower of Flesh and Blood (Za Ginī Piggu: Chiniku no Hana?: 1985) – which focus on the terrorising and murder of hapless female victims and foreground the horrific over the comedic. While not the best in the series – Mermaid in a Manhole (Za Ginī Piggu: Manhōru no naka no Ningyo?: 1988) is the stand out film for me – He Never Dies is entertaining enough to seek out, especially as most of what was been written about the series focuses on the apparent misygonism of the first two films and has resulted in the other films in the series being criminally overlooked.

The premise for the Guinea Pig films, is found footage, supposedly real events captured on video tape, and indeed according to urban myth Charlie Sheen mistaking fiction for reality after seeing one of the first two films called in the FBI to investigate these ‘snuff’ films. However, He Never Dies abandons the found footage aspect, for a more mondo documentary approach with an American scientist introducing us to the video footage, and commenting on the events as they take place. Despite his insistence that ‘this is reality captured on film’, He Never Dies never pretends to be real footage – unlike the previous two films – switching between black and white and colour footage as we watch Hideski’s attempts to kill himself become ever more frenetic and outrageous. The mobile camera eschewing the fixed POV of the earlier ones, attests to its cinematic, that is its fictional, nature.

The tone of the film is gross-out comedy rather than gross-out horror. As Hideshi continues to be unable to die, or feel pain, his attempts become more and more outrageous, and the film descends into gross out farce. Finally, having been dismembered, disembowelled and decapitated, Hideshi is transformed into a series of disconnected body parts – his head adorning his table, with one of his hands perched on his head as if it was a hat. Having said this, and despite the carnivalesque nature of He Never Dies, there is a serious message about the alienation and isolation that resulted from Japan’s drive to modernisation and economic prosperity in the 1960s and 1970s, which is rendered here as elsewhere as a crisis in masculinity. Hideshi is a cog in the mechanical wheel, with no real friends or family connections – no-one cares whether he lives or dies, his existence is meaningless. This is highlighted through a series of direct addresses to camera by his work colleagues and boss. In one such address, three female workers complain about Japanese men and in particular about the lack of attractive men in the Company foregrounding this crisis in masculinity.

When Hideshi reaches out to one of his male colleagues, Nakamura, for help (to die), Nakamura is in bed with Kyoko, Hideshi’s ex-girlfriend. He asks Nakamura to come to his apartment bringing with him a hatchet and a pair of gardening sheers. In the demented logic of Guinea Pig, the fact that Nakamura is also Hideshi’s gardener doesn’t seem that farfetched even though it stretches the viewer’s credibility.

And of course, this reference to gardening is an intertextual link to the previous film, Flower of Flesh and Blood, in which a deranged gardener utilizes female body parts in order to fertilise his garden. When Nakamura arrives with Kyoko in tow, their reaction to Hideshi’s plight is not one of concern for his plight but rather a concern for the mess that he has made through his multiple attempts to kill himself and what his landlord will make of the mess. The viewer cannot help but feel sympathy for Hideshi here, it is almost as if he is invisible, although he cannot die, it is almost as if he was dead – it is after all a matter of semantics.

He Never Dies is well worth seeking out, it is a great deal of fun to watch and you do not need to have seen the first two films in order to enjoy it. As a counterpart to the female victimisation of the prior films, He Never Dies with its emphasis on male masochism is a refreshing change of direction for the Guinea Pig films.

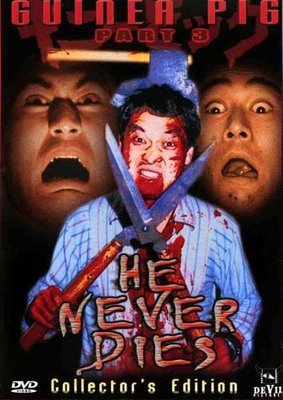

Guinea Pig: He Never Dies

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews