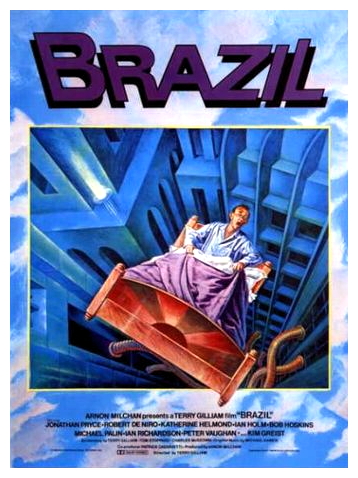

“In a highly structured and bureaucratic state, the government has installed extreme and highly counterproductive measures for which to track down terrorists. A ‘bug’ in the system mixes up the last name of a terrorist (Tuttle) and an innocent man (ironically enough Buttle). Thus, the wrong man (Buttle) is arrested and killed while Tuttle continues to roam free. Sam Lowry, an average man with a mother who ‘knows people’ is assigned to investigate the error. At the same time, Jill Layton, Buttle’s neighbor, is trying to report the mistake to authorities. Due to the extremely inefficient bureaucracy, she finds the process to be very tedious. Meanwhile, Sam Lowry, who has been dreaming about Jill, gets sidetracked by his fantasies and ends up also being a victim of the counter productivity of the government.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

British television comedy received a good shot in the arm with Monty Python’s Flying Circus, a weekly half-hour sketch show that ran for several seasons during the early seventies. It was satirical and disrespectful, but not so much about immediate political targets as much as the general absurdity of modern life, bureaucracies and authority figures. The team consisted of writer-performers Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Michael Palin, and also Terry Gilliam who produced the darkly comic animated cartoons and links, which often consisted of such cosmic injustices as huge feet appearing from the sky to squash people, or giant monster cats devouring London. When the series ended, the group reassembled from time-to-time to make movies. And Now For Something Completely Different (1971) was merely a rehash of their television sketches for the American market. The first original film was Monty Python And The Holy Grail (1974), followed by Monty Python’s Life Of Brian (1979) and Monty Python’s The Meaning Of Life (1983).

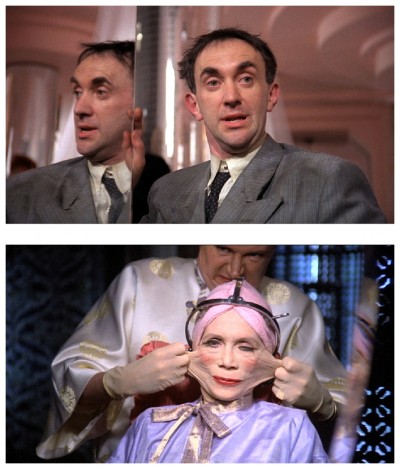

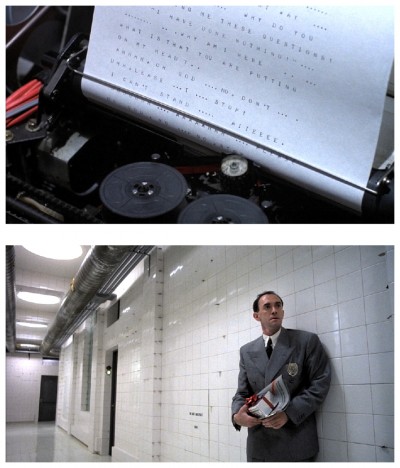

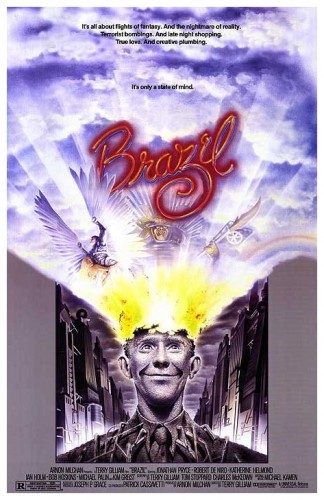

Terry Gilliam’s fiercely imaginative and blackly comic adaptation of a George Orwell-style dystopia, Brazil (1985), converts Nineteen Eighty-Four‘s chilling indictment of fascism and Stalinism into a satire on modern bureaucracy, consumerism and the Thatcher-Regan era, making it the director’s most outspokenly conceptual film. Brazil starts at 8.49am somewhere in the twentieth century, when a literal bug in the system replaces the last name of a suspected terrorist – Tuttle – with that of an innocent shoe repairman – Buttle – who is then interrogated and killed. Bumbling polite Britishers apologetically perform the strong-arm tactics we normally associate with KGB agents or uniformed police.

Terry Gilliam’s fiercely imaginative and blackly comic adaptation of a George Orwell-style dystopia, Brazil (1985), converts Nineteen Eighty-Four‘s chilling indictment of fascism and Stalinism into a satire on modern bureaucracy, consumerism and the Thatcher-Regan era, making it the director’s most outspokenly conceptual film. Brazil starts at 8.49am somewhere in the twentieth century, when a literal bug in the system replaces the last name of a suspected terrorist – Tuttle – with that of an innocent shoe repairman – Buttle – who is then interrogated and killed. Bumbling polite Britishers apologetically perform the strong-arm tactics we normally associate with KGB agents or uniformed police.

We think of Cold War bureaucracies as being lethally efficient like in Orwell’s novel, but the one Gilliam presents us with is more inefficient as ever. Things break down constantly (elevators, gadgets, heating, etc.) and mistakes are made by the dozen. Meanwhile, low-level public servant and latter-day Winston Smith Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) escapes in his dreams where, accompanied by the kitschy samba strains of Aquarela Do Brasil by Ary Baroso, he soars above the clouds, an Icarus-winged knight in shining armour who rescues a gauze-shrouded blonde damsel-in-distress (Kim Greist). Promoted to the Ministry Of Information, he tracks down the error and meets the Buttles’ outraged neighbour – his dream girl – who actually chain-smokes and drives a monster truck. Breaking protocol left, right and centre, and getting in way over his head, Sam is inevitably interrogated as a terrorist himself.

We think of Cold War bureaucracies as being lethally efficient like in Orwell’s novel, but the one Gilliam presents us with is more inefficient as ever. Things break down constantly (elevators, gadgets, heating, etc.) and mistakes are made by the dozen. Meanwhile, low-level public servant and latter-day Winston Smith Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) escapes in his dreams where, accompanied by the kitschy samba strains of Aquarela Do Brasil by Ary Baroso, he soars above the clouds, an Icarus-winged knight in shining armour who rescues a gauze-shrouded blonde damsel-in-distress (Kim Greist). Promoted to the Ministry Of Information, he tracks down the error and meets the Buttles’ outraged neighbour – his dream girl – who actually chain-smokes and drives a monster truck. Breaking protocol left, right and centre, and getting in way over his head, Sam is inevitably interrogated as a terrorist himself.

When he is arrested and about to be tortured by his former friend (Michael Palin), who should rescue him (at least in his mind) but a terrorist? Gilliam has made the bureaucracy so despicable and the general public so obnoxious that we’re actually willing to accept a terrorist as a hero. The ending is the reverse of Kurt Vonnegut‘s Slaughterhouse Five (1972) because, instead of leaving us in the brain-dead character’s happy dream world, we move away from Sam’s happy dream and back to the real world for the sorry sight of the true Sam. The final image gives logic to his ‘dream sequences’ and it should also be noted that the film’s controversial ending is much happier than Nineteen Eighty-Four’s because, in this case, a totalitarian regime cannot control a person’s dreams.

When he is arrested and about to be tortured by his former friend (Michael Palin), who should rescue him (at least in his mind) but a terrorist? Gilliam has made the bureaucracy so despicable and the general public so obnoxious that we’re actually willing to accept a terrorist as a hero. The ending is the reverse of Kurt Vonnegut‘s Slaughterhouse Five (1972) because, instead of leaving us in the brain-dead character’s happy dream world, we move away from Sam’s happy dream and back to the real world for the sorry sight of the true Sam. The final image gives logic to his ‘dream sequences’ and it should also be noted that the film’s controversial ending is much happier than Nineteen Eighty-Four’s because, in this case, a totalitarian regime cannot control a person’s dreams.

Reality taking flight in the midst of crisis is an everyday occurrence in the films of Terry Gilliam, the auteur behind Jabberwocky (1977), Time Bandits (1981), The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen (1988), The Fisher King (1991), Twelve Monkeys (1995), Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas (1998), The Brothers Grimm (2005), Tideland (2005), and The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus (2009). In a strange case of life reflecting art, the film Brazil itself became a victim of bureaucracy, making it famous even before its release. Displeased with the film’s dark tone, Universal Picture‘s then-president Sid Sheinberg wanted to revoke Gilliam’s final cut privilege by changing the ending to be more upbeat. The director responded with a full-page ad in Variety accusing Sheinberg of unjustly holding up the film’s release. The deadlock ended with Gilliam’s cut remaining intact after the Los Angeles Critics Awards bestowed Brazil with honours for Best Picture, Best Screenplay and Best Director. This came about because the shrewd Gilliam had arranged a secret screening for critics.

Reality taking flight in the midst of crisis is an everyday occurrence in the films of Terry Gilliam, the auteur behind Jabberwocky (1977), Time Bandits (1981), The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen (1988), The Fisher King (1991), Twelve Monkeys (1995), Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas (1998), The Brothers Grimm (2005), Tideland (2005), and The Imaginarium Of Doctor Parnassus (2009). In a strange case of life reflecting art, the film Brazil itself became a victim of bureaucracy, making it famous even before its release. Displeased with the film’s dark tone, Universal Picture‘s then-president Sid Sheinberg wanted to revoke Gilliam’s final cut privilege by changing the ending to be more upbeat. The director responded with a full-page ad in Variety accusing Sheinberg of unjustly holding up the film’s release. The deadlock ended with Gilliam’s cut remaining intact after the Los Angeles Critics Awards bestowed Brazil with honours for Best Picture, Best Screenplay and Best Director. This came about because the shrewd Gilliam had arranged a secret screening for critics.

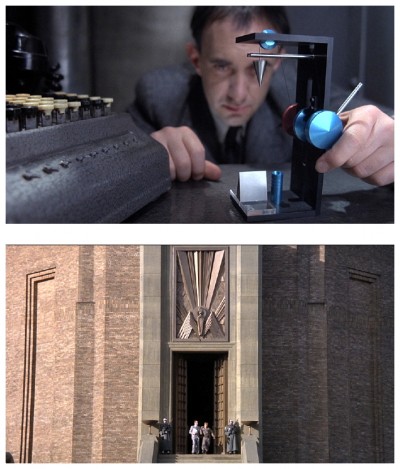

Brazil, co-written by Tom Stoppard and Charles McKeown, is the darkest of Gilliam’s trilogy concerning the triumphant imagination of dreamers, which includes Time Bandits and Baron Munchausen. True, Sam’s nightmares are often revelations – the giant Samurai warrior composed of microchips whose face is revealed to be his own, or his dreams of flying interrupted by skyscrapers erupting from the ground – but his daydreams are purely escapist and utterly conventional in a Secret Life Of Walter Mitty (1947) kind of way, and the film’s true revolutionary Tuttle (Robert DeNiro), a guerilla-style heating duct repairman who swoops down from the tops of buildings to short-circuit Central Services, is literally smothered by swirling paperwork and vanishes, the last figment of Sam’s extinguished mind.

Brazil, co-written by Tom Stoppard and Charles McKeown, is the darkest of Gilliam’s trilogy concerning the triumphant imagination of dreamers, which includes Time Bandits and Baron Munchausen. True, Sam’s nightmares are often revelations – the giant Samurai warrior composed of microchips whose face is revealed to be his own, or his dreams of flying interrupted by skyscrapers erupting from the ground – but his daydreams are purely escapist and utterly conventional in a Secret Life Of Walter Mitty (1947) kind of way, and the film’s true revolutionary Tuttle (Robert DeNiro), a guerilla-style heating duct repairman who swoops down from the tops of buildings to short-circuit Central Services, is literally smothered by swirling paperwork and vanishes, the last figment of Sam’s extinguished mind.

Gilliam goes the Kafka route rather than the Orwell route, conveying his ideas through art design, visual style and a wildly comic sensibility. Swarming with wonderful sight gags and visual delights, the film obsessively repeats a claustrophobic ‘iron cage’ motif of block-like building units, cubicles and boxes. A black comedy of brilliant excess about surveillance, terrorism and office culture, Brazil remains topical, rightfully recognised as Gilliam’s masterpiece and one of the most visionary films of the eighties. Gilliam’s obvious lack of optimism with his adult contemporaries is a motif that runs throughout his body of work. He is forced to strike a compromise between his mind’s childlike view of life, and the experienced knowledge of the seventy-year-old body that it now inhabits. His coy sense of naivete feeds such diverse yet thematically similar films. And it’s on that thought I’ll bid you a good night and ask you to be sure to return next week with a stout heart, an iron stomach and a titanium bladder for another head-melting romp through the garden of unearthly delights known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Gilliam goes the Kafka route rather than the Orwell route, conveying his ideas through art design, visual style and a wildly comic sensibility. Swarming with wonderful sight gags and visual delights, the film obsessively repeats a claustrophobic ‘iron cage’ motif of block-like building units, cubicles and boxes. A black comedy of brilliant excess about surveillance, terrorism and office culture, Brazil remains topical, rightfully recognised as Gilliam’s masterpiece and one of the most visionary films of the eighties. Gilliam’s obvious lack of optimism with his adult contemporaries is a motif that runs throughout his body of work. He is forced to strike a compromise between his mind’s childlike view of life, and the experienced knowledge of the seventy-year-old body that it now inhabits. His coy sense of naivete feeds such diverse yet thematically similar films. And it’s on that thought I’ll bid you a good night and ask you to be sure to return next week with a stout heart, an iron stomach and a titanium bladder for another head-melting romp through the garden of unearthly delights known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

![StrawDogs_Blu-ray[1]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/StrawDogs_Blu-ray1-e1315008980485-310x165.jpg)

Nicely written, Mr. Honeybone. The one thing you missed out on was mentioning that ‘Brazil’ is likely the best movie ever made with only a few contenders (A Clockwork Orange) that might displace it.