“A supposedly idyllic weekend trip to the countryside turns into a never-ending nightmare of traffic jams, revolution, cannibalism and murder as French bourgeois society starts to collapse under the weight of its own consumer preoccupations.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

For most of the sixties, genre cinema had been going through a very quiet period and, incidentally, not making any money for the film studios either. Of the few real hits in fantastic films between 1960 and 1967, most were on the fringe at best. The major commercial successes were Doctor No (1962), The Birds (1963), Doctor Strangelove (1964), Mary Poppins (1964) and You Only Live Twice (1967). Apart from Mary Poppins’ ability to levitate, there wasn’t much in the way of hardcore supernatural or science fiction effects in any of these. But everything was to change in 1968, the year of the big breakthrough. Curiously enough, the first signs of a renewed interest in genre cinema came from France rather than from Hollywood.

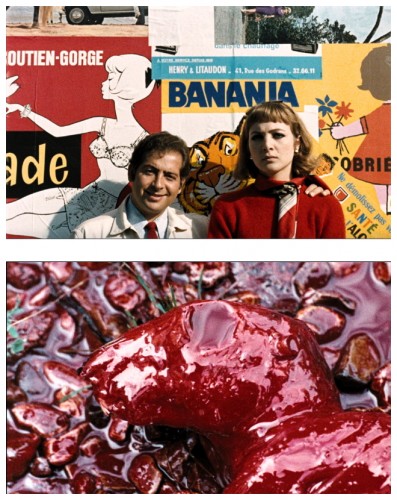

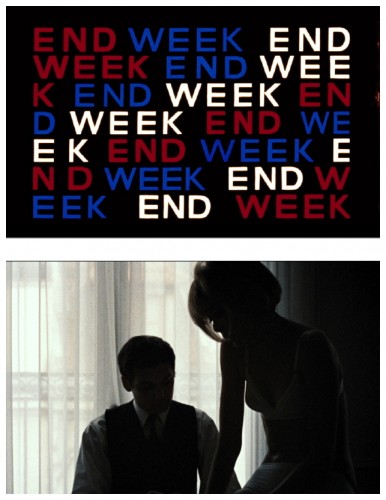

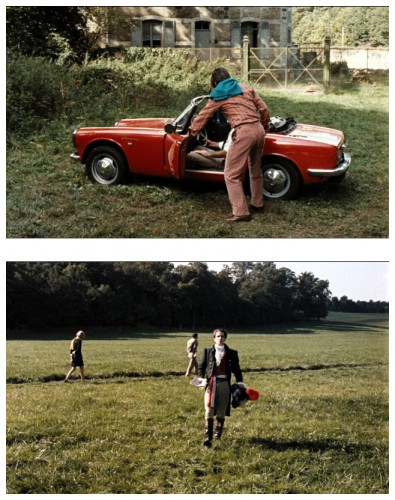

Fantasy had always been popular with French intellectuals, and it was one of the most intellectual of New Wave film directors who surprised the world by showing that science fiction scenarios could be taken seriously by so-called ‘artistic’ filmmakers. Jean-Luc Godard‘s Weekend (1967) remains a disturbingly effective and blackly amusing fantasy when viewed today. It begins realistically enough with a highly sexed couple named Corinne (Mirelle Darc) and Roland (Jean Yanne) preparing to drive off for a dirty weekend. Unfortunately, most of the population of Paris also seems to be driving to the countryside at the same time, and an extraordinary sequence follows, starting with minor traffic jams and dented fenders, escalating into a conflagration of violence and death on the roads.

Fantasy had always been popular with French intellectuals, and it was one of the most intellectual of New Wave film directors who surprised the world by showing that science fiction scenarios could be taken seriously by so-called ‘artistic’ filmmakers. Jean-Luc Godard‘s Weekend (1967) remains a disturbingly effective and blackly amusing fantasy when viewed today. It begins realistically enough with a highly sexed couple named Corinne (Mirelle Darc) and Roland (Jean Yanne) preparing to drive off for a dirty weekend. Unfortunately, most of the population of Paris also seems to be driving to the countryside at the same time, and an extraordinary sequence follows, starting with minor traffic jams and dented fenders, escalating into a conflagration of violence and death on the roads.

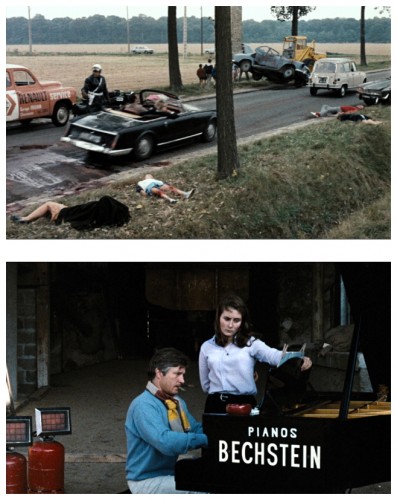

One of the most surreal tracking shots in cinema history moves slowly along a line of jammed cars, revealing more and more blood, death and destruction as it goes. At the beginning of this long shot we are still in the real world – by its end we have reached a kind of motorised apocalypse. In what is meant to represent bourgeois hell, fires devour the wrecked autos, dead bodies line the roads, and irritating left-wingers of all types come up to our insensitive travelers to spout their radical philosophies. Roland crashes the car (Corinne screams through the blood, “My handbag! My Hermes handbag!”) so they try to steal a car to continue their journey. When that fails, they attempt to hitchhike but are repeatedly turned down when they fail to answer political questions correctly – Roland gets rejected when he says he’d rather sleep with Lyndon Johnson than Mao.

One of the most surreal tracking shots in cinema history moves slowly along a line of jammed cars, revealing more and more blood, death and destruction as it goes. At the beginning of this long shot we are still in the real world – by its end we have reached a kind of motorised apocalypse. In what is meant to represent bourgeois hell, fires devour the wrecked autos, dead bodies line the roads, and irritating left-wingers of all types come up to our insensitive travelers to spout their radical philosophies. Roland crashes the car (Corinne screams through the blood, “My handbag! My Hermes handbag!”) so they try to steal a car to continue their journey. When that fails, they attempt to hitchhike but are repeatedly turned down when they fail to answer political questions correctly – Roland gets rejected when he says he’d rather sleep with Lyndon Johnson than Mao.

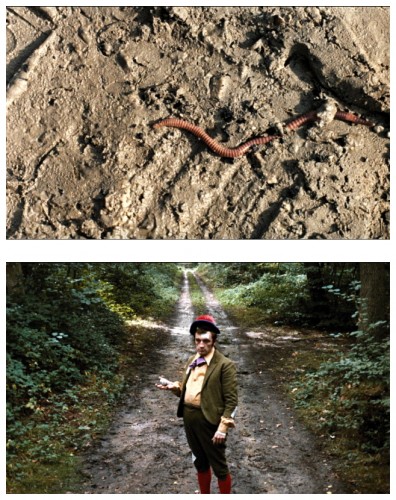

It also seems that Maoist guerilla forces have revolted, while philosophical characters dressed in eighteenth-century costumes roam the countryside reading aloud and, by the end of the film, the survivors are plunged into a scenario of civil war and cannibalism: Corinne does an about-face that Patty Hearst would have been proud of, and joins the guerillas and eventually devours Roland’s corpse ravenously. After all, by 1968, social unrest was endemic in the Western world, and it was the year in which student riots practically tore Paris apart, making Godard’s film even more relevant when it was first released.

It also seems that Maoist guerilla forces have revolted, while philosophical characters dressed in eighteenth-century costumes roam the countryside reading aloud and, by the end of the film, the survivors are plunged into a scenario of civil war and cannibalism: Corinne does an about-face that Patty Hearst would have been proud of, and joins the guerillas and eventually devours Roland’s corpse ravenously. After all, by 1968, social unrest was endemic in the Western world, and it was the year in which student riots practically tore Paris apart, making Godard’s film even more relevant when it was first released.

Godard includes moments of political discourse, as well as references to his favourite films – Gösta Berling (1924), Johnny Guitar (1954), The Searchers (1956) – and quips about the relation of art to to reality, but his main goal was to make his arrogant cruel bourgeois couple literally go through hell. Weekend is an absurdist tale, but it also highly political, exhibiting a kind of cranky-comic Marxism. Material possessions, technology and consumerism have corrupted this lunatic world. A girl whose lover has been killed when their car collides with a tractor screams at its working-class driver that, as opposed to him, “We can screw on the Riviera or in ski resorts!” in a manic if irrelevant exultation, since her partner lies dead beside her.

Godard includes moments of political discourse, as well as references to his favourite films – Gösta Berling (1924), Johnny Guitar (1954), The Searchers (1956) – and quips about the relation of art to to reality, but his main goal was to make his arrogant cruel bourgeois couple literally go through hell. Weekend is an absurdist tale, but it also highly political, exhibiting a kind of cranky-comic Marxism. Material possessions, technology and consumerism have corrupted this lunatic world. A girl whose lover has been killed when their car collides with a tractor screams at its working-class driver that, as opposed to him, “We can screw on the Riviera or in ski resorts!” in a manic if irrelevant exultation, since her partner lies dead beside her.

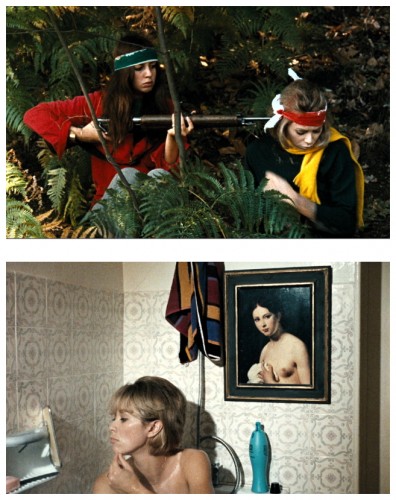

The film is visually memorable: Hysterical people running through a flock of incredibly white sheep, scattering them like the parting of some frothy Red Sea. A perverse sexual anecdote at the beginning, featuring the unusual conjunction of an egg and a vagina, is mirrored at the end, where the running white and yolk dripping over the heroine’s private parts seems to be a deranged metaphor for our own fantasy society gone quite wrong. Needless to say, this is not a film for children. Unfortunately, Godard’s New Wave devotees were bewildered by the science fiction elements, and the science fiction fans were not tuned in to French intellectual imagery, so the film, falling between two chairs, has never had the recognition it deserves despite all its pretentious excesses.

The film is visually memorable: Hysterical people running through a flock of incredibly white sheep, scattering them like the parting of some frothy Red Sea. A perverse sexual anecdote at the beginning, featuring the unusual conjunction of an egg and a vagina, is mirrored at the end, where the running white and yolk dripping over the heroine’s private parts seems to be a deranged metaphor for our own fantasy society gone quite wrong. Needless to say, this is not a film for children. Unfortunately, Godard’s New Wave devotees were bewildered by the science fiction elements, and the science fiction fans were not tuned in to French intellectual imagery, so the film, falling between two chairs, has never had the recognition it deserves despite all its pretentious excesses.

After the New Wave, Godard’s politics have been much less radical and his recent films are about representation and human conflict from a humanist or Marxist perspective. He has created one of the largest bodies of critical analysis of any filmmaker since the mid-twentieth century, and his work has been central to narrative theory and have challenged both commercial narrative cinema norms and film criticism’s vocabulary. In 2002 Sight & Sound magazine ranked Godard as third in the critics’ top ten directors of all-time and, in 2010, he was awarded an special honorary Oscar for his achievements, but apparently refused to attend the ceremony. And it’s with that rebellious thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier with another feather from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News! Toodles!

After the New Wave, Godard’s politics have been much less radical and his recent films are about representation and human conflict from a humanist or Marxist perspective. He has created one of the largest bodies of critical analysis of any filmmaker since the mid-twentieth century, and his work has been central to narrative theory and have challenged both commercial narrative cinema norms and film criticism’s vocabulary. In 2002 Sight & Sound magazine ranked Godard as third in the critics’ top ten directors of all-time and, in 2010, he was awarded an special honorary Oscar for his achievements, but apparently refused to attend the ceremony. And it’s with that rebellious thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier with another feather from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews