SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“A mysterious man, whose head is completely covered in bandages, wants a room. The proprietors of the pub aren’t used to making their house an inn during the winter months, but the man insists. They soon come to regret their decision. The man quickly runs out of money, and he has a violent temper besides. Worse still, he seems to be some kind of chemist and has filled his room with messy chemicals, test tubes, beakers and the like. When they try to throw him out, they make a ghastly discovery. Meanwhile, Flora Cranley appeals to her father to do something about the mysterious disappearance of Doctor Griffin, his assistant and her sweetheart. Her father’s other assistant, the cowardly Doctor Kemp, is no help. He wants her for himself. Little does Flora guess that the wild tales, from newspapers and radio broadcasts, of an invisible homicidal maniac are stories of Doctor Griffin himself, who has discovered the secret of invisibility and gone mad in the process.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Hats (and bandages) must be taken off to any film that boasts a lead role that you can’t see. Claude Rains‘ fully-clad portrayal of The Invisible Man (1933) is unparalleled when it comes to invisible men. James Whale‘s version of the H.G. Wells classic remains the most iconic, blending science fiction, the supernatural, and groundbreaking special effects with sly black comedy and suspense. It should not be forgotten, however, that Claude’s transparent role is pure evil, a man consumed by the desire to have the world groveling at his feet – a contemptuous being that wreaks havoc and thrives on mass destruction and anarchy. The only glimmer of humanity emerges in his love for Flora (Gloria Stuart), but this isn’t enough to prevent his inevitable self-destruction. He’s mad, he’s bad and he’s invisible! A true classic not to be missed.

Scientific knowledge was never one of the requirements needed for a successful Hollywood scriptwriter. At least science fiction authors are usually aware of scientific flaws and try to disguise them with pseudo-science. For instance, they’ve long got around Einstein’s law regarding the impossibility of faster-than-light travel by taking a short-cut through ‘hyper-space’. My old friend Herbert George Wells was well aware of the fact that a totally transparent man would also be totally blind, since the light would pass straight through the retinas of the eyes without exciting the optic nerves, but instead he diverted attention to all the other problems of being invisible (such as half-digested meals still being visible within the body for several hours) in his marvelous novel The Invisible Man.

Scientific knowledge was never one of the requirements needed for a successful Hollywood scriptwriter. At least science fiction authors are usually aware of scientific flaws and try to disguise them with pseudo-science. For instance, they’ve long got around Einstein’s law regarding the impossibility of faster-than-light travel by taking a short-cut through ‘hyper-space’. My old friend Herbert George Wells was well aware of the fact that a totally transparent man would also be totally blind, since the light would pass straight through the retinas of the eyes without exciting the optic nerves, but instead he diverted attention to all the other problems of being invisible (such as half-digested meals still being visible within the body for several hours) in his marvelous novel The Invisible Man.

Many of the more interesting elements in H.G.’s novel were discarded when it came to being adapted for the screen but the film The Invisible Man still remains a very impressive and entertaining piece of work, though Wells himself didn’t share that opinion. He was, however, fortunate in having a very talented team of people involved in the production of the film. The director was James Whale, who had just made Frankenstein (1931), the script was by R.C. Sherriff (ably assisted by Philip Wylie and Preston Sturges), Claude Rains was cast in the lead, and top effects man John P. Fulton handled the special effects. Whale and Sherriff may have diluted some of the horror in their adaptation, but they did concentrate on the strong streak of black humour that runs through the book and the result was a very amusing picture in which the comedy was far more than a shade sick. There is also a great deal of gleeful anarchy in it, and Whale had more sympathy with the invisible man (who has been turned into a raving megalomaniac due to a side-effect of the invisibility drug) than with his victims. He certainly seemed to derive pleasure from making the British policemen in the film look ridiculous.

Many of the more interesting elements in H.G.’s novel were discarded when it came to being adapted for the screen but the film The Invisible Man still remains a very impressive and entertaining piece of work, though Wells himself didn’t share that opinion. He was, however, fortunate in having a very talented team of people involved in the production of the film. The director was James Whale, who had just made Frankenstein (1931), the script was by R.C. Sherriff (ably assisted by Philip Wylie and Preston Sturges), Claude Rains was cast in the lead, and top effects man John P. Fulton handled the special effects. Whale and Sherriff may have diluted some of the horror in their adaptation, but they did concentrate on the strong streak of black humour that runs through the book and the result was a very amusing picture in which the comedy was far more than a shade sick. There is also a great deal of gleeful anarchy in it, and Whale had more sympathy with the invisible man (who has been turned into a raving megalomaniac due to a side-effect of the invisibility drug) than with his victims. He certainly seemed to derive pleasure from making the British policemen in the film look ridiculous.

Sherriff’s script retained the outline of H.G.’s original novel while modernising (and simplifying) the concepts behind it. None of the earlier treatments handed to Whale had actually referred to the novel, which was out-of-print in the United States at the time. The problem, carefully explained in a typical bit of thirties techno-babble by kindly old scientist (Henry Travers), is a substance called Monocaine, which draws colour from everything it touches. We are told that it was used for bleaching cloth before being abandoned because it destroyed the material and that next, mysteriously, they tried it on a dog, turning it dead white and sent it raving mad. Ignoring the insanity side-effect – but soon to fall foul of it – Griffin injects the drug into himself for reasons that are hard to imagine. Certainly, from the first time we meet him, he is ranting about its potential to hold governments to ransom, enslave the world, rob, rape and kill! This is no misunderstood well-intentioned monster – instead of grim satisfaction, Griffin derives mischievous delight from the mayhem he unleashes.

Sherriff’s script retained the outline of H.G.’s original novel while modernising (and simplifying) the concepts behind it. None of the earlier treatments handed to Whale had actually referred to the novel, which was out-of-print in the United States at the time. The problem, carefully explained in a typical bit of thirties techno-babble by kindly old scientist (Henry Travers), is a substance called Monocaine, which draws colour from everything it touches. We are told that it was used for bleaching cloth before being abandoned because it destroyed the material and that next, mysteriously, they tried it on a dog, turning it dead white and sent it raving mad. Ignoring the insanity side-effect – but soon to fall foul of it – Griffin injects the drug into himself for reasons that are hard to imagine. Certainly, from the first time we meet him, he is ranting about its potential to hold governments to ransom, enslave the world, rob, rape and kill! This is no misunderstood well-intentioned monster – instead of grim satisfaction, Griffin derives mischievous delight from the mayhem he unleashes.

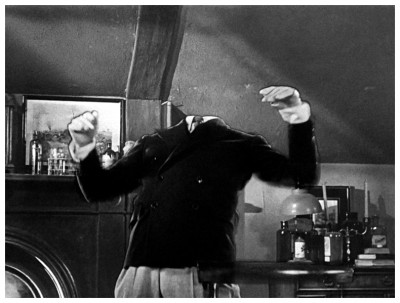

As the mad scientist Griffin, Claude Rains gives a memorable performance despite being heard but not seen for most of the film. In the early scenes his face is covered in bandages and it’s not until he dies in the hospital that the audience catches a glimpse of him. I’ve always enjoyed his great acting talents, and found his over-acting most amusing. It wasn’t until after this film that Claude went on to become a great dramatic actor, appearing in Casablanca (1942) and many greater starring roles. He never needed cue cards and always remembered his many long lines to perfection, something considered a remarkable feat in Hollywood of today. Anyway, for the rest of the film he is entirely invisible or represented by various articles of apparently empty clothing – shirts, trousers, dressing gowns and so on. John P. Fulton, in charge of the effects department at Universal for many years, made use of an improved traveling matte system based on one originally devised by effects innovator Frank Williams, whose assistant he had once been.

As the mad scientist Griffin, Claude Rains gives a memorable performance despite being heard but not seen for most of the film. In the early scenes his face is covered in bandages and it’s not until he dies in the hospital that the audience catches a glimpse of him. I’ve always enjoyed his great acting talents, and found his over-acting most amusing. It wasn’t until after this film that Claude went on to become a great dramatic actor, appearing in Casablanca (1942) and many greater starring roles. He never needed cue cards and always remembered his many long lines to perfection, something considered a remarkable feat in Hollywood of today. Anyway, for the rest of the film he is entirely invisible or represented by various articles of apparently empty clothing – shirts, trousers, dressing gowns and so on. John P. Fulton, in charge of the effects department at Universal for many years, made use of an improved traveling matte system based on one originally devised by effects innovator Frank Williams, whose assistant he had once been.

The Invisible Man was named by the New York Times as one of the Ten Best Films Of The Year, but H.G. once told me that, while he liked the picture he had one grave fault to find with it: It had taken his brilliant scientist and changed him into a lunatic, a liberty he could not condone. Despite his misgivings, H.G. praised the performance of Una O’Connor as the screaming Mrs. Hall, and the film made a fortune for Universal which led to the creation of their third major monster movie franchise. Curt Siodmak and Joe May co-wrote the screenplay for The Invisible Man Returns (1939) starring Vincent Price, which Joe had directed. Joe, like Curt, was a self-exiled German and had been prominent in the German film industry from its earliest days directing serials and thrillers – his real name was Joseph Mandel. The pair regrouped to write the story for The Invisible Woman (1940) directed by Edward Sutherland. It’s a light-hearted and moderately amusing film whose only real claim to fame was that it featured one of the first full-frontal female nudes in commercial cinema. True, it was an invisible nude, but back in the forties it was the thought that counted to the adolescent males in the audience.

The Invisible Man was named by the New York Times as one of the Ten Best Films Of The Year, but H.G. once told me that, while he liked the picture he had one grave fault to find with it: It had taken his brilliant scientist and changed him into a lunatic, a liberty he could not condone. Despite his misgivings, H.G. praised the performance of Una O’Connor as the screaming Mrs. Hall, and the film made a fortune for Universal which led to the creation of their third major monster movie franchise. Curt Siodmak and Joe May co-wrote the screenplay for The Invisible Man Returns (1939) starring Vincent Price, which Joe had directed. Joe, like Curt, was a self-exiled German and had been prominent in the German film industry from its earliest days directing serials and thrillers – his real name was Joseph Mandel. The pair regrouped to write the story for The Invisible Woman (1940) directed by Edward Sutherland. It’s a light-hearted and moderately amusing film whose only real claim to fame was that it featured one of the first full-frontal female nudes in commercial cinema. True, it was an invisible nude, but back in the forties it was the thought that counted to the adolescent males in the audience.

Soon it was the female audiences turn to be titillated by the sight of the invisible Jon Hall who appeared, as it were, in The Invisible Agent (1942). Curt’s screenplay had the son of the original invisible man (now calling himself Frank Raymond) volunteering to the US authorities shortly after Pearl Harbour, to use what little remained of the invisibility serum on a secret mission in Germany. He is then parachuted, invisible, from a plane over Berlin and once on the ground he makes successful contact with a female agent (Ilona Massey) who, understandably, takes a little time to adjust to his unique ‘appearance’. Soon afterward she receives a visit from the head of the ‘secret Nazi police’ who discloses that Hitler plans an immediate attack on the USA. With the girl’s help the invisible man secures a list belonging to a Japanese spy called Ikito (Peter Lorre doing a sort of villainous Mister Moto routine) which contains the names of all the Nazi and Japanese spies in America. Ikito almost succeeds in trapping him with a silk net lined with sharp hooks but, though injured, he escapes. Then he and the girl commandeer a German bomber and fly back to England, a stunt performed with casual regularity in Hollywood films during the war.

Soon it was the female audiences turn to be titillated by the sight of the invisible Jon Hall who appeared, as it were, in The Invisible Agent (1942). Curt’s screenplay had the son of the original invisible man (now calling himself Frank Raymond) volunteering to the US authorities shortly after Pearl Harbour, to use what little remained of the invisibility serum on a secret mission in Germany. He is then parachuted, invisible, from a plane over Berlin and once on the ground he makes successful contact with a female agent (Ilona Massey) who, understandably, takes a little time to adjust to his unique ‘appearance’. Soon afterward she receives a visit from the head of the ‘secret Nazi police’ who discloses that Hitler plans an immediate attack on the USA. With the girl’s help the invisible man secures a list belonging to a Japanese spy called Ikito (Peter Lorre doing a sort of villainous Mister Moto routine) which contains the names of all the Nazi and Japanese spies in America. Ikito almost succeeds in trapping him with a silk net lined with sharp hooks but, though injured, he escapes. Then he and the girl commandeer a German bomber and fly back to England, a stunt performed with casual regularity in Hollywood films during the war.

Though pure escapism, The Invisible Agent is completely different in tone from the frivolous The Invisible Woman, a sign of how quickly even comic book characters were harnessed to the propaganda machine. It’s a typical Hollywood irony that, in this case, it was a German writer providing the propaganda. The war was ignored in the next installment of The Invisible Man saga, but the downbeat mood was continued in The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944) directed by Ford Beebe and written by Bertram Millhauser. Jon Hall once again played the lead character but, for the first time since the 1933 version, he was an unsympathetic one, and his end was suitably macabre – killed by an invisible Great Dane.

Though pure escapism, The Invisible Agent is completely different in tone from the frivolous The Invisible Woman, a sign of how quickly even comic book characters were harnessed to the propaganda machine. It’s a typical Hollywood irony that, in this case, it was a German writer providing the propaganda. The war was ignored in the next installment of The Invisible Man saga, but the downbeat mood was continued in The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944) directed by Ford Beebe and written by Bertram Millhauser. Jon Hall once again played the lead character but, for the first time since the 1933 version, he was an unsympathetic one, and his end was suitably macabre – killed by an invisible Great Dane.

And with that The Invisible Man saga came to an end on the cinema screen, though his character did re-emerge on television now and then, first in a British-made adventure series in 1957 and then in an American series in 1975, finally to have H.G.’s original novel given the respect it deserved in the 1984 BBC six-part television serial. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll bid you pleasant dreams and look forward to doing the zombie stomp with you again next week when I have the opportunity to lay at your feet another dead bird from the dodgy chicken shop known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

And with that The Invisible Man saga came to an end on the cinema screen, though his character did re-emerge on television now and then, first in a British-made adventure series in 1957 and then in an American series in 1975, finally to have H.G.’s original novel given the respect it deserved in the 1984 BBC six-part television serial. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll bid you pleasant dreams and look forward to doing the zombie stomp with you again next week when I have the opportunity to lay at your feet another dead bird from the dodgy chicken shop known as Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

The Invisible Man (1933) is now available on Blu ray per Universal Studios on the “Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection”

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews