The forties got off to a cracking start with Paramount’s Technicolor production of Doctor Cyclops (1940) starring Albert Dekker as a crazed scientist who discovers the secret of miniaturisation deep in the South American jungles. The film contains superb special effects sequences which required the construction of gigantic sets and props of everyday articles, including books, chairs, pot-plants and scientific instruments. Universal Studios, while reluctant to invest their horror films with big budgets, also turned out some interesting films during the forties. Once again John P. Fulton worked his magic for The Invisible Man Returns (1940), the comedy The Invisible Woman (1940), The Invisible Agent (1942) and The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944), although none of the wit and charm which had made James Whale’s original so memorable.

The forties got off to a cracking start with Paramount’s Technicolor production of Doctor Cyclops (1940) starring Albert Dekker as a crazed scientist who discovers the secret of miniaturisation deep in the South American jungles. The film contains superb special effects sequences which required the construction of gigantic sets and props of everyday articles, including books, chairs, pot-plants and scientific instruments. Universal Studios, while reluctant to invest their horror films with big budgets, also turned out some interesting films during the forties. Once again John P. Fulton worked his magic for The Invisible Man Returns (1940), the comedy The Invisible Woman (1940), The Invisible Agent (1942) and The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944), although none of the wit and charm which had made James Whale’s original so memorable.

The one major big-budget fantasy film contributed by Universal during the decade was The Wolf Man (1941) directed by George Waggner and starring Lon Chaney Junior as the cursed Larry Talbot. Oddly enough, the screenplay by Curt Siodmak, while wholly fictional in its definitions of werewolf lore and legend, worked so persuasively that the details it contained were considered for many years to be the real thing. Bela Lugosi was relegated to a minor role, that of the werewolf who initially attacks Chaney and sets the curse of lycanthropy in motion.

It’s a tribute to Jack Pierce‘s makeup that his werewolf design would be considered definitive for many years to come. To achieve the transformation, the actor was positioned on the floor or armchair, his clothes carefully pinned down to prevent movement while the four-hour makeup was applied in stages, a piece at a time. Pierce carefully applied the yak hair to Chaney’s face and several frames of film exposed, then more hair applied and several more frames exposed, a variation of the stop-motion method of animation. After filming, the processed negative was put in the optical printer and each separate shot was overlapped, creating a series of smooth dissolves. It was a technique Pierce was to use again and again for the series of Universal monster rallies produced throughout the forties.

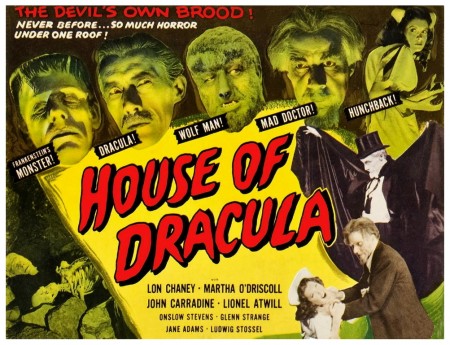

In Frankenstein Meets The Wolfman (1943), Talbot had an encounter with Frankenstein’s monster (Bela Lugosi). Although formula, the climax of the movie with the two monsters slugging it out remains memorable. Larry Talbot got together with Dracula (John Carradine), Frankenstein (Boris Karloff) and his monster (Glenn Strange) in The House Of Frankenstein (1944). Karloff made something of a comeback to Universal after working for Columbia in low-budget B-grade films for several years. This team-up proved successful enough to warrant a re-match in The House Of Dracula (1945).

In Frankenstein Meets The Wolfman (1943), Talbot had an encounter with Frankenstein’s monster (Bela Lugosi). Although formula, the climax of the movie with the two monsters slugging it out remains memorable. Larry Talbot got together with Dracula (John Carradine), Frankenstein (Boris Karloff) and his monster (Glenn Strange) in The House Of Frankenstein (1944). Karloff made something of a comeback to Universal after working for Columbia in low-budget B-grade films for several years. This team-up proved successful enough to warrant a re-match in The House Of Dracula (1945).

Again, Chaney, Strange and Carradine got together, although this time Dracula and the Wolf Man were trying to find a cure for their respective conditions. Carradine’s portrayal of Dracula is regarded by many to be one of the best, capturing not only Bram Stoker’s original vampire in looks but also in style and suave, sophisticated manners. It’s a true pity that John Carradine was never able to play the character in a proper Dracula feature.

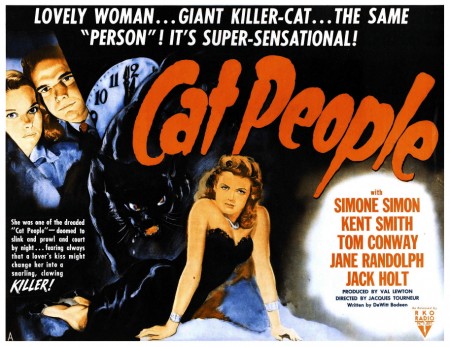

While Universal was cranking out low-budget reruns of their monster favourites throughout the forties – films like Ghost Of Frankenstein (1942), Frankenstein Meets The Wolfman, and Son Of Dracula (1942) with Lon Chaney Junior making the least impressive of screen vampires – RKO Studios were busily getting on with a series of minor masterpieces in the medium of the macabre under the guidance of producer Val Lewton. The Russian-born Lewton had been an editorial assistant to David O. Selznick during the thirties and had several books (both fiction and non-fiction) to his credit. In 1942 he was signed by RKO to lead a unit specifically producing low budget horror films based on titles that had been carefully market-researched. The first of these films was Cat People (1942) directed by Jacques Tourneur. This moody and often sombre film, about a woman (Simone Simon) who turns into a panther when sexually aroused, set the trends and styles of the truly remarkable series of films that followed.

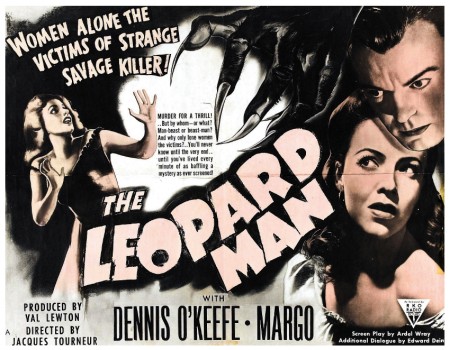

The following year saw no less than four features from the Lewton unit. I Walked With A Zombie (1943), again directed by Jacques Tourneur, told the haunting tale of a nurse who goes to work in the West Indies for a rich sugar planter, only to be drawn into a family mystery and the curse of voodoo. The Leopard Man (1943) based on the Cornell Woolrich novel Black Alibi, is a taut thriller about a killer loose in a small Mexican town. The twist in the tale was whether the violent attacker was a man or an escaped black panther. The Seventh Victim (1943) is undoubtedly the great Lewton masterpiece. An extraordinarily bleak story of despair contained within the framework of a mystery, as a young girl visits New York in hopes of finding her missing sister and discovers a web of intrigue surrounding a group of satanists.

The following year saw no less than four features from the Lewton unit. I Walked With A Zombie (1943), again directed by Jacques Tourneur, told the haunting tale of a nurse who goes to work in the West Indies for a rich sugar planter, only to be drawn into a family mystery and the curse of voodoo. The Leopard Man (1943) based on the Cornell Woolrich novel Black Alibi, is a taut thriller about a killer loose in a small Mexican town. The twist in the tale was whether the violent attacker was a man or an escaped black panther. The Seventh Victim (1943) is undoubtedly the great Lewton masterpiece. An extraordinarily bleak story of despair contained within the framework of a mystery, as a young girl visits New York in hopes of finding her missing sister and discovers a web of intrigue surrounding a group of satanists.

Audiences were deprived of seeing The Ghost Ship (1943) for nearly two years after its production when Warner Brothers took exception to its similarities with their own film The Sea Wolf (1941). While the central character of a megalomaniac sea captain is similar, the plots of the two films are completely different. Then came Curse Of The Cat People (1944) directed by Gunther Fritsch and former editor Robert Wise, who replaced Fritsch after a week’s shooting. While there are links with Lewton’s former success, they are only marginally relevant in this tale of a young girl and her imaginary playmate. Despite its lurid title, the film that emerged is a compelling study of a distressed child who escapes into a fantasy world of her own creation.

The following year saw two Lewton productions top-lining Boris Karloff. The first, The Body Snatcher (1945), is probably the producer’s most overt horror fable. Set in Edinburgh of the 1800s, it features Henry Daniell as a doctor who finds himself dealing with a psychotic body snatcher (Karloff) who provides him with cadavers for his medical research. Superbly lit and photographed, and with tight direction by Robert Wise, The Body Snatcher contains one sequence which has seldom been rivaled for extended shivers. Having killed the troublesome body snatcher, the doctor wraps him in a sheet and takes the corpse into the countryside to bury it. As the horse-drawn coach is whipped through a howling storm, the shrouded shape seems to come to life causing the doctor to drive the carriage off the road.

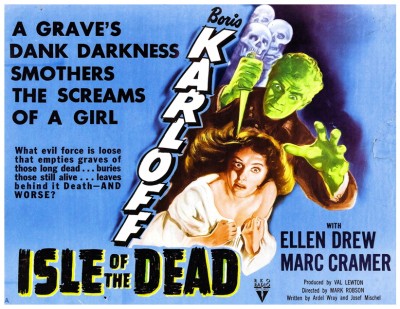

For Isle Of The Dead (1945), Lewton used the Hundred Years War as his backdrop, grouping a motley collection of characters on a plague-ridden island. Although the themes of premature burial and vampirism are hinted at, the film lacks an overall direction. Lewton’s final horror film was Bedlam (1946), again starring Boris Karloff. For his inspiration, Lewton used one of the more horrifying plates from The Rake’s Progress by Hogarth, which depicted the inside of an insane asylum. Karloff plays the cruel master of the inmates who gets his comeuppance after various acts of humiliation and degradation performed on his charges. Featuring convoluted screenplays co-written by Lewton (under the pseudonym Carlos Keith) and a multitude of characters, both Isle Of The Dead and Bedlam lack the power of some of the producer’s more straightforward works. But whatever shortcomings there might be, the entire body of work remains unique in the annals of fantasy cinema – a tribute to the abilities of a highly creative producer.

For Isle Of The Dead (1945), Lewton used the Hundred Years War as his backdrop, grouping a motley collection of characters on a plague-ridden island. Although the themes of premature burial and vampirism are hinted at, the film lacks an overall direction. Lewton’s final horror film was Bedlam (1946), again starring Boris Karloff. For his inspiration, Lewton used one of the more horrifying plates from The Rake’s Progress by Hogarth, which depicted the inside of an insane asylum. Karloff plays the cruel master of the inmates who gets his comeuppance after various acts of humiliation and degradation performed on his charges. Featuring convoluted screenplays co-written by Lewton (under the pseudonym Carlos Keith) and a multitude of characters, both Isle Of The Dead and Bedlam lack the power of some of the producer’s more straightforward works. But whatever shortcomings there might be, the entire body of work remains unique in the annals of fantasy cinema – a tribute to the abilities of a highly creative producer.

Typically, MGM were only concerning themselves with so-called ‘quality’ mainstream productions through the decade of World War Two. One exception was the lavishly-budgeted version of Doctor Jekyll And Mister Hyde (1941) directed by Victor Fleming and starring Spencer Tracy as Robert Louis Stevenson‘s misguided medico. Robert Donat had originally been cast in the role but was replaced by Tracy at the last minute – the miscasting was obvious. As fine an actor as Tracy was, he was simply wrong for the part and, with the emphasis more on the psychological rather than the psychotic aspects of the character and story, the resulting film borders on downright dull.

An altogether better film was Albert Lewin‘s The Picture Of Dorian Grey (1945) featuring Hurd Hatfield as Dorian, a young man granted eternal youth when he wistfully makes a wish in the presence of an ancient Egyptian statue. The director’s screenplay captures the best of Oscar Wilde‘s story, with George Sanders perfectly delivering Wilde’s witty epigrams with just the right hint of decadence. But Dorian pays a terrible price for his wish fulfillment – just as he stays young, so a life-size portrait shows the ravages of time and his pursuit of hedonism. Shot in lustrous black and white by Harry Stradling, the climax of the film is the discovery of the painting (in Technicolor), hidden away in a locked attic, and Dorian’s death.

An altogether better film was Albert Lewin‘s The Picture Of Dorian Grey (1945) featuring Hurd Hatfield as Dorian, a young man granted eternal youth when he wistfully makes a wish in the presence of an ancient Egyptian statue. The director’s screenplay captures the best of Oscar Wilde‘s story, with George Sanders perfectly delivering Wilde’s witty epigrams with just the right hint of decadence. But Dorian pays a terrible price for his wish fulfillment – just as he stays young, so a life-size portrait shows the ravages of time and his pursuit of hedonism. Shot in lustrous black and white by Harry Stradling, the climax of the film is the discovery of the painting (in Technicolor), hidden away in a locked attic, and Dorian’s death.

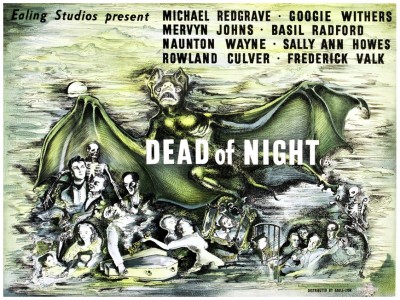

While Hollywood’s horror cycle was winding down, the English studio Ealing produced one of the most memorable horror films of the decade, Dead Of Night (1946). Based on four short horror stories by E.F. Benson, H.G. Wells, John Baines and Angus MacPhail, Dead Of Night is one of the first and still one of the best ‘omnibus’ or ‘anthology’ films. Each story was handled by a different director (Basil Dearden, Robert Hamer, Charles Crichton and Alberto Cavalcanti) and, of the four tales, the best is the one featuring Michael Redgrave as a ventriloquist whose dummy takes on a life of its own. The combination of Redgrave’s performance and Cavalcanti’s claustrophobic direction make this segment a high point of horror cinema.

While Hollywood’s horror cycle was winding down, the English studio Ealing produced one of the most memorable horror films of the decade, Dead Of Night (1946). Based on four short horror stories by E.F. Benson, H.G. Wells, John Baines and Angus MacPhail, Dead Of Night is one of the first and still one of the best ‘omnibus’ or ‘anthology’ films. Each story was handled by a different director (Basil Dearden, Robert Hamer, Charles Crichton and Alberto Cavalcanti) and, of the four tales, the best is the one featuring Michael Redgrave as a ventriloquist whose dummy takes on a life of its own. The combination of Redgrave’s performance and Cavalcanti’s claustrophobic direction make this segment a high point of horror cinema.

By 1948 it was obvious that audiences were bored with the classic monsters of yore. World War Two had provided the public with quite enough real horror through the pages of magazines, newspapers and, more importantly, on a weekly basis at their local theatres as millions of feet of newsreels were unspooled showing, first hand, the devastation of war. Out of the war emerged a double-threat villain – the Bomb and Communism – both of which would prove a fruitful source of fantasy film makers throughout the fifties. But in the closing years of the decade, Universal found one more way to squeeze just a little more cash from their gallery of monsters – they would meet Bud Abbott and Lou Costello!

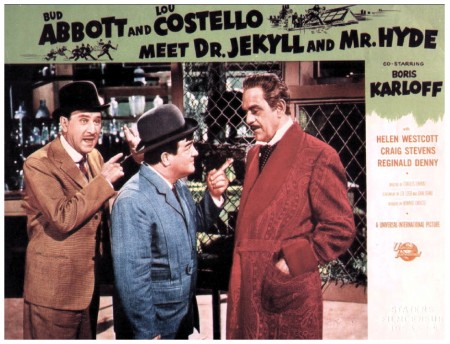

Under Charles Barton‘s direction, Abbott And Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) was to prove the best of a quickly deteriorating series. Lugosi was back as Dracula, Chaney as the Wolf Man and Glenn Strange as Frankenstein’s monster. The plot hinges on the search for a new brain for the monster, and what better one to use than Lou Costello’s? Where Abbott And Costello Meet Frankenstein succeeds is the treatment of the horror scenes, all played straight, with a high production standard attached to them. Sadly, this attitude was not adopted for the series of films that followed. In rapid succession the ex-vaudevillians met the Invisible Man, Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde, the Killer, Boris Karloff and, in the worst of the lot, the Mummy. It’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week to have your innocence violated beyond description again while I force you to submit to the horrors of Hollywood on a budget for…Horror News! Toodles!

Also: see

1920s Genre Films

1930s Genre Films

1950s Genre Films

1960s Genre Films

1970s Genre Films

1980s Genre Films.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews