SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“In a cyberpunk vision of the future, man has developed the technology to create replicants, human clones used to serve in the colonies outside Earth but with fixed lifespans. In Los Angeles, 2019, Deckard is a Blade Runner, a cop who specializes in terminating replicants. Originally in retirement, he is forced to re-enter the force when four replicants escape from an off-world colony to Earth.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Even though his genre output has been limited, Ridley Scott has been more influential than most other directors, not only because he is more mainstream but because he did something new in science fiction movies – he created a genuine feeling of foreignness. He is a master of elaborately different settings, in which places removed from us in space or time are not simply sketched in with a couple of alien-seeming artifacts. They are vividly, solidly realised in the round. After Scott, the design of science fiction movies can never be the same again. When Scott graduated from London’s prestigious Royal College Of Art, he was taken on by BBC Television as a set designer and was sent on a production course (he was famously offered the chance to design the Daleks for Doctor Who, but passed on the assignment because he insisted he didn’t like science fiction).

His first full-scale television work was directing two episodes of Z-Cars, a low-key realist police series not unlike The Bill. After three years, Scott set out on his own filming commercials and became something of a legend in the advertising business. It was almost by accident that he was given a feature to direct, after more than a decade in marketing, but the result attracted a lot of attention. The Duellists (1977) is an offbeat and colourful historical romance, set in France during the Napoleonic era, about two soldiers (one working-class, one aristocratic) whose enmity is such that they fight a series of duels over a period that stretches through most of their adult lives. This was followed by Alien (1979), a monster movie based on a script by Dan O’Bannon, writer, star and co-director of Dark Star (1974). Scott’s direction is impeccable, not just in the building of tension, but in the realism he evokes for what is essentially a B-grade story, especially the underplayed, convincing delivery of dialogue.

His first full-scale television work was directing two episodes of Z-Cars, a low-key realist police series not unlike The Bill. After three years, Scott set out on his own filming commercials and became something of a legend in the advertising business. It was almost by accident that he was given a feature to direct, after more than a decade in marketing, but the result attracted a lot of attention. The Duellists (1977) is an offbeat and colourful historical romance, set in France during the Napoleonic era, about two soldiers (one working-class, one aristocratic) whose enmity is such that they fight a series of duels over a period that stretches through most of their adult lives. This was followed by Alien (1979), a monster movie based on a script by Dan O’Bannon, writer, star and co-director of Dark Star (1974). Scott’s direction is impeccable, not just in the building of tension, but in the realism he evokes for what is essentially a B-grade story, especially the underplayed, convincing delivery of dialogue.

He obtains a particularly good performance from Sigourney Weaver as the hard-bitten, slightly unsympathetic woman survivor, although some conventionally-minded viewers might have preferred a more charmingly feminine person in the role (which would have destroyed the film’s edgy quality). Many film fans assumed that Alien was a one-off from a slightly arty film-maker who would now return with relief to mainstream cinema. They were completely wrong. Scott’s next venture was science fiction again, but far more sophisticated than 95% of all previously filmed science fiction. Blade Runner (1982) was based on Philip K. Dick‘s classic Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? first published in 1968, an almost surrealist novel about the relationship between man and machine, tenderness and cruelty in an entropic future Earth that is slowly going down the plug-hole (and almost devoid of animal life), where most healthy people with money have emigrated to other planets or live in fortress-like dwellings protected from the poor people who flood the streets.

He obtains a particularly good performance from Sigourney Weaver as the hard-bitten, slightly unsympathetic woman survivor, although some conventionally-minded viewers might have preferred a more charmingly feminine person in the role (which would have destroyed the film’s edgy quality). Many film fans assumed that Alien was a one-off from a slightly arty film-maker who would now return with relief to mainstream cinema. They were completely wrong. Scott’s next venture was science fiction again, but far more sophisticated than 95% of all previously filmed science fiction. Blade Runner (1982) was based on Philip K. Dick‘s classic Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? first published in 1968, an almost surrealist novel about the relationship between man and machine, tenderness and cruelty in an entropic future Earth that is slowly going down the plug-hole (and almost devoid of animal life), where most healthy people with money have emigrated to other planets or live in fortress-like dwellings protected from the poor people who flood the streets.

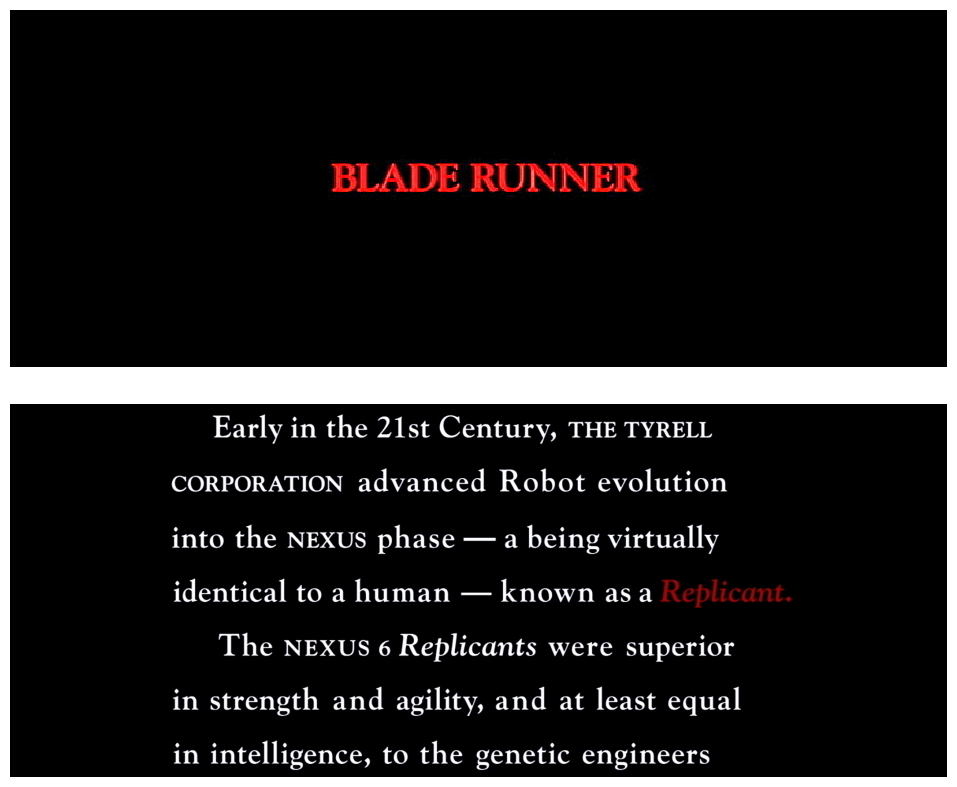

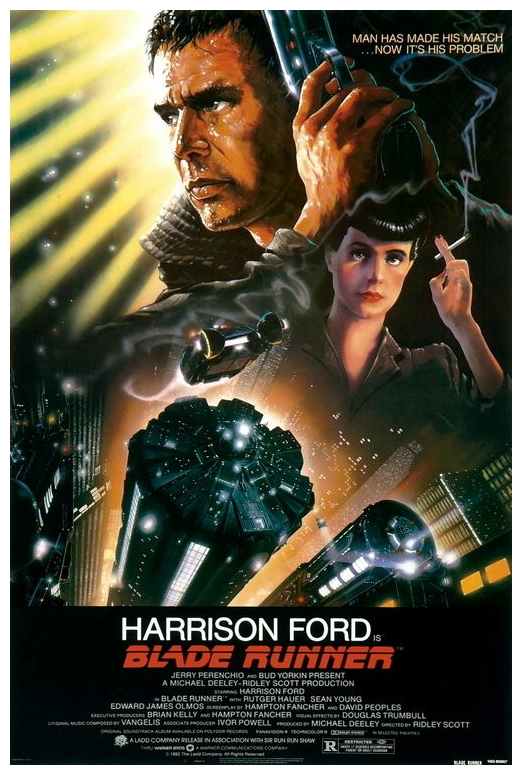

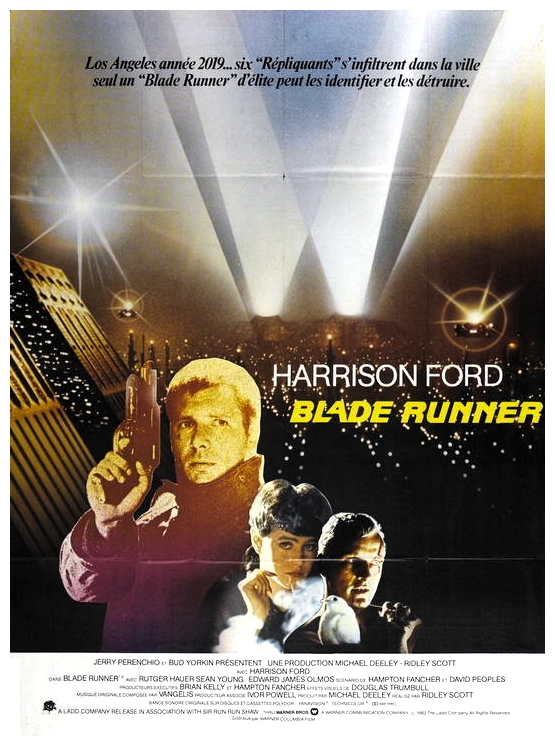

The screenplay jettisons many elements of Dick’s novel (fairly late in the production in some cases) leaving some rather puzzling sequences. For example, the film doesn’t really make it clear that the rarity of real animal life has led to a thriving trade in robot copies of animals which, in turn, renders baffling a sequence in which the empathy-quotient of a suspected android is tested by asking questions about dead animals. These androids, called replicants in the film, are artificial human slaves who have escaped to revenge themselves on the human race, and especially upon the scientist-entrepreneur who created them, Doctor Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel). Harrison Ford plays bounty hunter Rick Deckard, grim, unshaven and Bogart-like, whose task it is to locate and destroy these dangerous creatures who have superhuman strength and are highly intelligent.

The screenplay jettisons many elements of Dick’s novel (fairly late in the production in some cases) leaving some rather puzzling sequences. For example, the film doesn’t really make it clear that the rarity of real animal life has led to a thriving trade in robot copies of animals which, in turn, renders baffling a sequence in which the empathy-quotient of a suspected android is tested by asking questions about dead animals. These androids, called replicants in the film, are artificial human slaves who have escaped to revenge themselves on the human race, and especially upon the scientist-entrepreneur who created them, Doctor Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel). Harrison Ford plays bounty hunter Rick Deckard, grim, unshaven and Bogart-like, whose task it is to locate and destroy these dangerous creatures who have superhuman strength and are highly intelligent.

Deckard hates his job, but the encounter with these replicants will make him question his own identity and humanity. Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) is the group’s mastermind, bent on meeting his maker and asking for an upgrade. To utilise an appropriately Noir phrase, these replicants are basically D.O.A. – haunted by ‘accelerated decrepitude’ their mission is futile from the very beginning. Still, Batty wants to find out if their maker can repair what he makes: “All he wanted were the same answers the rest of us want. Where did I come from? Where am I going? How long have I got?” Like some sort of Byronic rebel, Batty is a Lucifer figure who destroys his maker in a poignant scene whose tragic overtones are peerless not only in the science fiction genre, but cinema in general. In a strangely poetic ending, Lucifer evolves into a Christ figure, saving the life of his would-be killer.

Deckard hates his job, but the encounter with these replicants will make him question his own identity and humanity. Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) is the group’s mastermind, bent on meeting his maker and asking for an upgrade. To utilise an appropriately Noir phrase, these replicants are basically D.O.A. – haunted by ‘accelerated decrepitude’ their mission is futile from the very beginning. Still, Batty wants to find out if their maker can repair what he makes: “All he wanted were the same answers the rest of us want. Where did I come from? Where am I going? How long have I got?” Like some sort of Byronic rebel, Batty is a Lucifer figure who destroys his maker in a poignant scene whose tragic overtones are peerless not only in the science fiction genre, but cinema in general. In a strangely poetic ending, Lucifer evolves into a Christ figure, saving the life of his would-be killer.

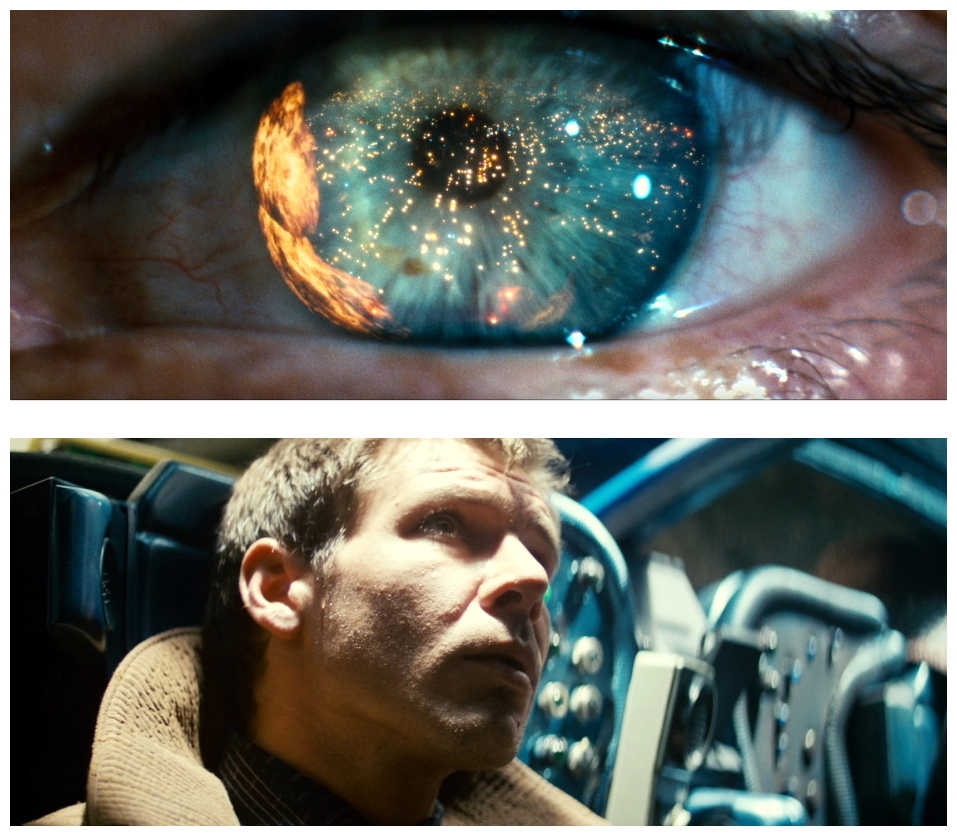

Technically a machine, Batty poignantly strives for a soul: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.” The original release of Blade Runner was cut in such a way that its subtext was almost invisible. I don’t suppose that more than one in ten viewers understood (also ambiguous in the novel) that Deckard, the slayer of replicants, may be a specialised replicant himself without knowing it. He has a curiously intermittent deficiency in human feelings and is emotionally distant, not unlike the replicants he hunts. There is a subtle point being expressed here about what actually makes us human, and about destruction making us less human.

Technically a machine, Batty poignantly strives for a soul: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.” The original release of Blade Runner was cut in such a way that its subtext was almost invisible. I don’t suppose that more than one in ten viewers understood (also ambiguous in the novel) that Deckard, the slayer of replicants, may be a specialised replicant himself without knowing it. He has a curiously intermittent deficiency in human feelings and is emotionally distant, not unlike the replicants he hunts. There is a subtle point being expressed here about what actually makes us human, and about destruction making us less human.

For a genre movie, Blade Runner is very adult indeed, arguably the first thinking-person’s science fiction film since 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or Solaris (1972). Despite various incoherences in the narrative development and an appallingly sentimental scene tacked on the end by Warner Brothers so as to not make the whole effect seem too pessimistic – Deckard driving off into the sunset surrounded by lush mountains with his replicant lover (Sean Young) by his side – Blade Runner is extraordinary science fiction. Its strength is the wonderful fullness of the way the near-future Los Angeles of 2019 is visualised: crowded, tacky, half-visible through rain and steam, blending high technology with near-universal decay and heavily orientalised (the film was co-produced by Sir Run Run Shaw).

For a genre movie, Blade Runner is very adult indeed, arguably the first thinking-person’s science fiction film since 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or Solaris (1972). Despite various incoherences in the narrative development and an appallingly sentimental scene tacked on the end by Warner Brothers so as to not make the whole effect seem too pessimistic – Deckard driving off into the sunset surrounded by lush mountains with his replicant lover (Sean Young) by his side – Blade Runner is extraordinary science fiction. Its strength is the wonderful fullness of the way the near-future Los Angeles of 2019 is visualised: crowded, tacky, half-visible through rain and steam, blending high technology with near-universal decay and heavily orientalised (the film was co-produced by Sir Run Run Shaw).

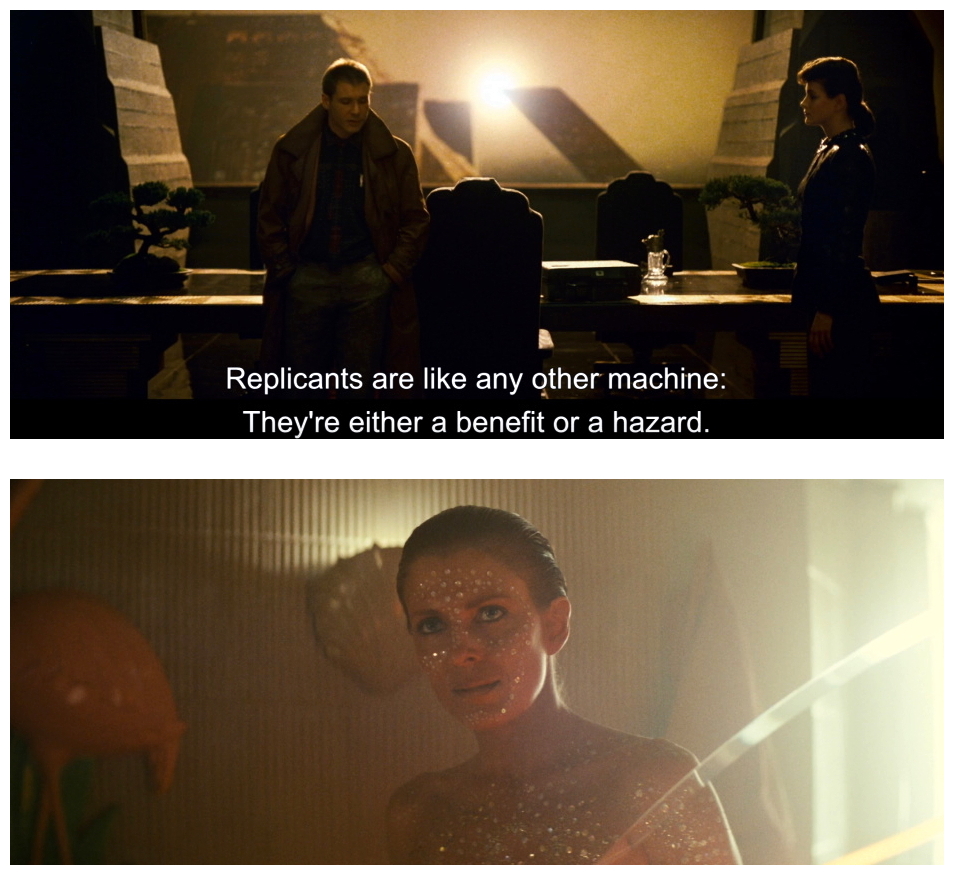

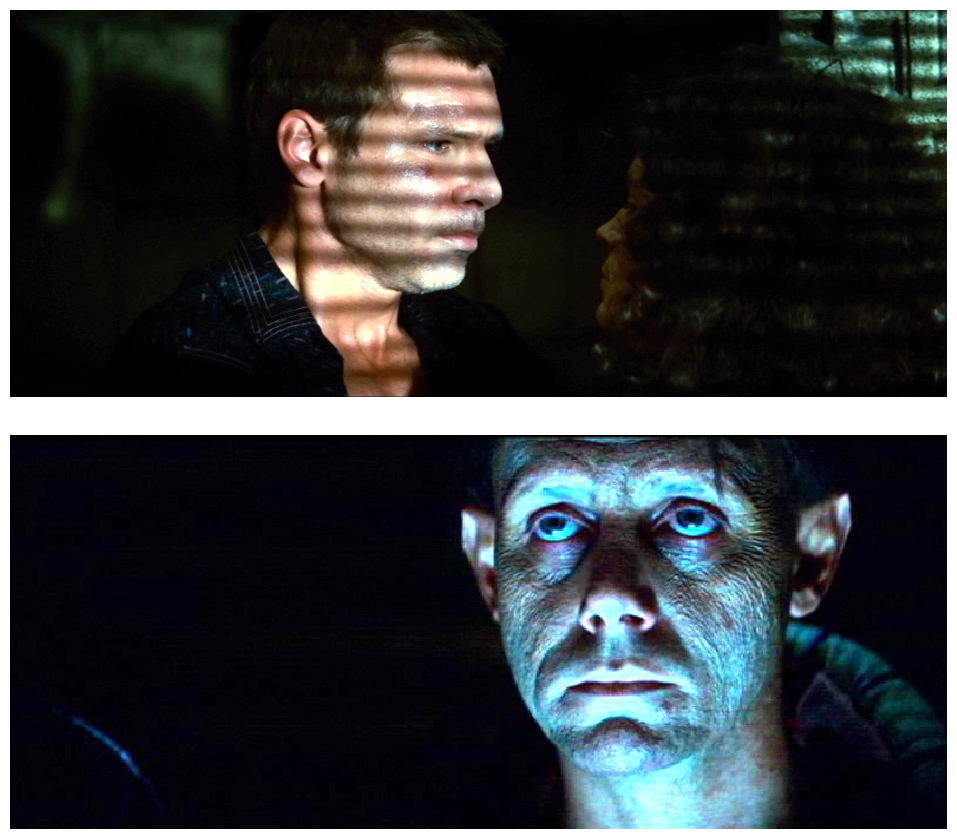

Visually the film is enormously exciting, but not in an obvious way. Scott makes heavy use of chiaroscuro – the bizarre sets are shadowy, dimly lit, with shafts of light producing unexpected illuminations. The replicants are wonderfully presented too, with four virtually unknown actors at the time – Rutger Hauer, Brion James, Joanna Cassidy and Daryl Hannah – as replicants on the run. They’re all animal grace and physical perfection, bubbling with a kind of frenetic energy, yet also curiously mechanical and capable of bursting into an oddly inhuman scarifying violence, with no more visible emotion than somebody else might feel when swatting a fly. The inhuman image is almost perfectly captured when Pris (Daryl Hannah) conceals herself amid a crowd of life-size clockwork dolls, and suddenly erupts into a violent attack on Deckard which is simultaneously a narcissistic display of gymnastics. It is an uncanny scene, partly cut for the original American release but restored in the more vicious British version.

Visually the film is enormously exciting, but not in an obvious way. Scott makes heavy use of chiaroscuro – the bizarre sets are shadowy, dimly lit, with shafts of light producing unexpected illuminations. The replicants are wonderfully presented too, with four virtually unknown actors at the time – Rutger Hauer, Brion James, Joanna Cassidy and Daryl Hannah – as replicants on the run. They’re all animal grace and physical perfection, bubbling with a kind of frenetic energy, yet also curiously mechanical and capable of bursting into an oddly inhuman scarifying violence, with no more visible emotion than somebody else might feel when swatting a fly. The inhuman image is almost perfectly captured when Pris (Daryl Hannah) conceals herself amid a crowd of life-size clockwork dolls, and suddenly erupts into a violent attack on Deckard which is simultaneously a narcissistic display of gymnastics. It is an uncanny scene, partly cut for the original American release but restored in the more vicious British version.

The film is indeed disturbing for the squeamish, but the violence is unavoidably intrinsic to its central point. The film has several exciting action sequences – Deckard chasing Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) through the streets, being cornered by brutal Leon (Brion James), being surprised by acrobatic Pris, battling Batty on a building ledge – but it’s very deliberately paced and characterised by an overwhelming sense of melancholy and beautiful memories lost. Even the replicants have been provided with memories of their non-existent childhoods. Scott’s masterly direction evokes an alien world which has evolved visibly from our own, and presents the most compelling vision of the future since Metropolis (1926). Los Angeles is weirdly futuristic yet some of the main sequences are set in some of the oldest buildings in the city, such as the famously familiar Bradbury Building. Like Alien (1979) and H.R. Giger, Scott worked closely with an artist to help visualise the details. This time it was Syd Mead, a well-known industrial designer and ‘futurist’ whose gouache renderings were vividly brought to life by art director David Snyder, production designer Lawrence Paull, and special effects maestro Douglas Trumbull.

The film is indeed disturbing for the squeamish, but the violence is unavoidably intrinsic to its central point. The film has several exciting action sequences – Deckard chasing Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) through the streets, being cornered by brutal Leon (Brion James), being surprised by acrobatic Pris, battling Batty on a building ledge – but it’s very deliberately paced and characterised by an overwhelming sense of melancholy and beautiful memories lost. Even the replicants have been provided with memories of their non-existent childhoods. Scott’s masterly direction evokes an alien world which has evolved visibly from our own, and presents the most compelling vision of the future since Metropolis (1926). Los Angeles is weirdly futuristic yet some of the main sequences are set in some of the oldest buildings in the city, such as the famously familiar Bradbury Building. Like Alien (1979) and H.R. Giger, Scott worked closely with an artist to help visualise the details. This time it was Syd Mead, a well-known industrial designer and ‘futurist’ whose gouache renderings were vividly brought to life by art director David Snyder, production designer Lawrence Paull, and special effects maestro Douglas Trumbull.

Together they created a crowded, hazy city full huge deserted retro-fitted buildings where acid rain falls constantly, electric advertising covers the sides of buildings, and police vehicles known as ‘spinners’ fly about. It all looks terribly decrepit and so very unhealthy. The atmosphere is enhanced by the superb soundscape by Vangelis and Jordan Cronenweth‘s moody photography, and the performances are excellent throughout, including Sean Young‘s memorable turn as a replicant femme fatale. Unlike Alien, Blade Runner is more than a magnificent mise-en-scène – this time settings and narrative cohere into a striking whole, a film of thoughtful, intricate substance, partly sustained by a convincing performance from Harrison Ford. Nevertheless it did have one big problem, namely the unfortunate voice-over narration by Ford in the style of Raymond Chandler‘s gritty detective Philip Marlowe proved too much and strikes a false note, but this was thankfully removed from later releases.

Together they created a crowded, hazy city full huge deserted retro-fitted buildings where acid rain falls constantly, electric advertising covers the sides of buildings, and police vehicles known as ‘spinners’ fly about. It all looks terribly decrepit and so very unhealthy. The atmosphere is enhanced by the superb soundscape by Vangelis and Jordan Cronenweth‘s moody photography, and the performances are excellent throughout, including Sean Young‘s memorable turn as a replicant femme fatale. Unlike Alien, Blade Runner is more than a magnificent mise-en-scène – this time settings and narrative cohere into a striking whole, a film of thoughtful, intricate substance, partly sustained by a convincing performance from Harrison Ford. Nevertheless it did have one big problem, namely the unfortunate voice-over narration by Ford in the style of Raymond Chandler‘s gritty detective Philip Marlowe proved too much and strikes a false note, but this was thankfully removed from later releases.

I have one other tiny problem with the story. Most film fans nowadays are well-aware that it is suggested that Deckard is himself a replicant but, if that was so, then the final confrontation between Deckard and Batty wouldn’t have any special meaning. When Batty allows Deckard to live, this should represent the ultimate gesture between man and machine, giving hope that we can live in harmony. Speaking of which, keep an eye out (ow!) for a schlocky classic entitled The Creation Of The Humanoids (1962), made two decades before Blade Runner and six years before the release of Philip K. Dick‘s novel. Earth’s population has been decimated by nuclear war, so they create human-like androids to assist rebuilding civilisation, but the robots rebel and go to war with the remnants of humanity. The central character is militant Captain Cragis, a man who despises androids, only to discover by the end that he himself is an android, but I digress.

I have one other tiny problem with the story. Most film fans nowadays are well-aware that it is suggested that Deckard is himself a replicant but, if that was so, then the final confrontation between Deckard and Batty wouldn’t have any special meaning. When Batty allows Deckard to live, this should represent the ultimate gesture between man and machine, giving hope that we can live in harmony. Speaking of which, keep an eye out (ow!) for a schlocky classic entitled The Creation Of The Humanoids (1962), made two decades before Blade Runner and six years before the release of Philip K. Dick‘s novel. Earth’s population has been decimated by nuclear war, so they create human-like androids to assist rebuilding civilisation, but the robots rebel and go to war with the remnants of humanity. The central character is militant Captain Cragis, a man who despises androids, only to discover by the end that he himself is an android, but I digress.

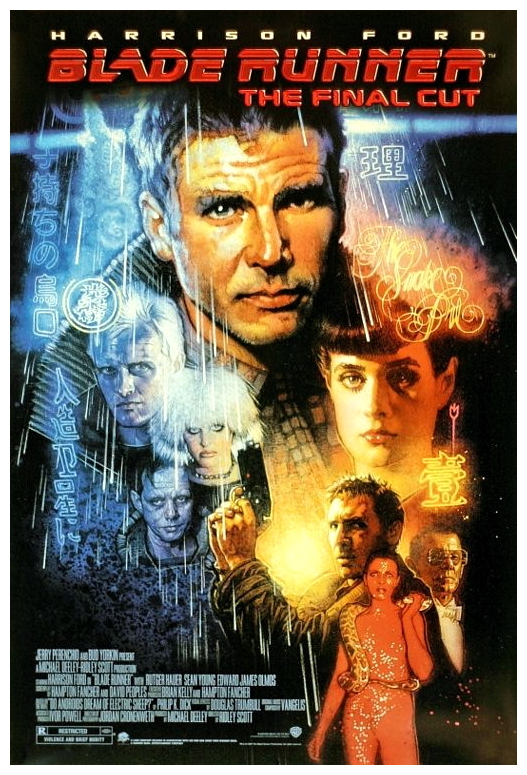

Several different versions of Blade Runner have been released over the last three decades. Two versions were screened in 1982, the American release and the European release. The European version was re-released in the early nineties as a ‘director’s cut’ which removed Ford’s Noir-style narration and the studio-imposed happy ending, and restored the unicorn dream sequence. The Final Cut, the only edition which Scott had complete control over, was released in 2007 and contains four discs absolutely chockablock full of special features. This ‘Final Cut’ of the film is less than a minute longer but it has a few digital fixes and corrected continuity errors. There are three separate commentaries featuring eleven different speakers: one by director Ridley Scott; one by producers Hampton Fancher, David Peoples, Michael Deely and Katherine Haber; and one by designers Syd Mead, Lawrence Paull, David Snyder, Douglas Trumbull, Richard Yuricich and David Dryerand.

Several different versions of Blade Runner have been released over the last three decades. Two versions were screened in 1982, the American release and the European release. The European version was re-released in the early nineties as a ‘director’s cut’ which removed Ford’s Noir-style narration and the studio-imposed happy ending, and restored the unicorn dream sequence. The Final Cut, the only edition which Scott had complete control over, was released in 2007 and contains four discs absolutely chockablock full of special features. This ‘Final Cut’ of the film is less than a minute longer but it has a few digital fixes and corrected continuity errors. There are three separate commentaries featuring eleven different speakers: one by director Ridley Scott; one by producers Hampton Fancher, David Peoples, Michael Deely and Katherine Haber; and one by designers Syd Mead, Lawrence Paull, David Snyder, Douglas Trumbull, Richard Yuricich and David Dryerand.

Disc two features a lengthy (210 minutes) documentary entitled Dangerous Days: The Making Of Blade Runner, in which cast, crew, critics and colleagues give an in depth behind-the-scenes look at the film, from its literary roots to its controversial place in cinema history. Disc three has all three original releases of the film (1982 American, 1982 European, 1992 Director’s Cut), and disc four has the Enhancement Archive containing ninety minutes of rare footage and photos that cover the film’s amazing history, production, effects, impact, trailers, television ads and so much more. Plus galleries, audio interviews with Philip K. Dick, and more than a dozen featurettes. Throughout his lengthy career, Ridley Scott‘s sense of both the exotic and the mundane qualities to be found in alien worlds (even in The Duellists which is, after all, set in the alien world of the past) makes him one of the most creative of all genre film-makers. It’s on this rather upbeat note I’ll wrap-up this week’s burnt offering, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another cinematic pedigree from Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Disc two features a lengthy (210 minutes) documentary entitled Dangerous Days: The Making Of Blade Runner, in which cast, crew, critics and colleagues give an in depth behind-the-scenes look at the film, from its literary roots to its controversial place in cinema history. Disc three has all three original releases of the film (1982 American, 1982 European, 1992 Director’s Cut), and disc four has the Enhancement Archive containing ninety minutes of rare footage and photos that cover the film’s amazing history, production, effects, impact, trailers, television ads and so much more. Plus galleries, audio interviews with Philip K. Dick, and more than a dozen featurettes. Throughout his lengthy career, Ridley Scott‘s sense of both the exotic and the mundane qualities to be found in alien worlds (even in The Duellists which is, after all, set in the alien world of the past) makes him one of the most creative of all genre film-makers. It’s on this rather upbeat note I’ll wrap-up this week’s burnt offering, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another cinematic pedigree from Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

yr a really good writer, fwiw.

.The best movie ever!I I’m still amazed at the depth of it my go to movie for celebrating the new year