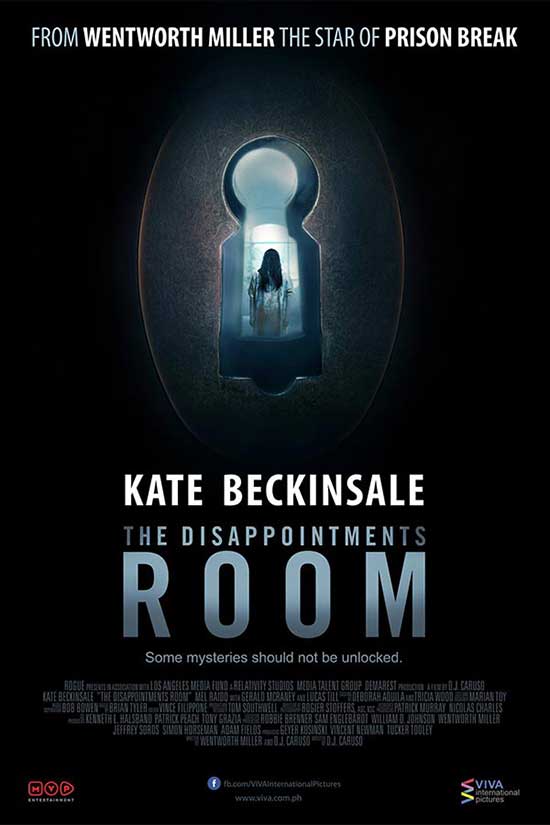

Starring the talented and lovely Kate Beckinsale (‘Underworld’, ‘The Widow’), 2016’s ‘The Disappointments Room’ followed a young couple and their son as they unraveled the ultimately horrifying secrets of a hidden room in the attic of their new home. The filmed based the core of it’s story on the real life discovery and investigation of just such a room by the actual Laurie and Jeffery Dumas in their colonial Rhode Island property. Fact and fiction may often walk hand in hand, but in the case of ‘The Disappointments Room’, the film remains just a step behind the morbid reality of Laurie Dumas’ story and its implications.*Spoilers Ahead*

The Actual Tale

While the film takes place on the haunting and picturesque grounds of Greensboro’s Adamsleigh Mansion, the actual home was a much more demure classic Rhode Island colonial built in 1857. While lacking much of the grandeur of it’s silver-screen counterpart, what it held inside it’s walls sparks both curiosity and appall.

Yes, upon purchasing the property the real Laurie and Jeffery Dumas did in fact find a secret room in the attic of their new home. In an interview with The Kent County Daily Times, Laurie stated that while preparing to rennovate the attic into a music room, she found a dirty rag which revealed the infamous drain below. This room, featured on HGTV’s ‘If Walls Could Talk’, only locked from the outside and was obviously intended for use by a child. With the exception of the foreboding floor drain, that’s where the structural similarities end between the actual home and the film’s rendition.

The real disappointments room was constructed much like a typical children’s playhouse instead of the spartan prison cell we saw on screen. Wood paneled with two exterior and two more interior windows – one could almost envision it as just that, a children’s area, built by a doting father. But then there’s the pesky little details of the external deadbolt and floor drain which quickly dissolve that warm notion.

Furthermore, records of the period paint a darker picture as well. While not the original owners, surely the most prominent were Judge Job Smith Carpenter and his wife Frances. Judge Carpenter being the obvious real-life inspiration for the film’s insidious villain Judge Blacker, played by Gerald McRaney (‘Longmire’, ‘Jericho’). The Carpenters were a well respected and well known couple throughout the area; this evidenced by myriad articles covering their lives and achievements, not to mention having a street, Carpenter Court, named for them. However, despite such esteem and coverage, what’s missing and most damning is the utter absence of their daughter, Ruth.

Born in February of 1895, Ruth Carpenter is unaccounted for in press and social clippings. It’s not until her death in 1900 that she finally receives acknowledgement in the form of a lone obituary in the local paper – seeming to imply it was the Carpenter’s intent to purposely keep Ruth out of sight and out of the public mind. Just as in the film, Laurie Dumas did indeed locate Ruth Carpenter’s gravestone – albeit in the family plot at the local cemetery, not the forgotten recesses of the garden.

As for the term ‘disappointments room’, Dumas was a member of the research department at West Warwick public library. It was here that the majority of her investigation took place and during a discussion with coworkers, another patron identified her find. A disappointment room being a purpose built room to hide or isolate a child or family member with disfigurement or disabilities that made them unfit for socialization. The term itself was regional,however the existence and practice of these rooms is anything but..

One famous and well documented case is that of Rosemary Kennedy. Sister to the late President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, Rosemary displayed mental deficiencies from a young age and was ultimately permanently maimed at the behest of her father (the clinical term being a lobotomy, but let’s call a duck a duck). Following this, she was moved to what became known as ‘The Kennedy Cottage’, built for her outside the grounds of St. Coletta’s School for Exceptional Children, where she lived out the rest of her days in relative solitude. Granted she was a Kennedy, so she got a cottage not a room – but the principle remains the same.

Other less affluent cases abound and armed with the above knowledge Laurie Dumas pieced together a rather compelling narrative about the life and fate of young Ruth Carpenter. In reality no supernatural or paranormal activity was ever reported by the Dumas’ or any other residents, but even without spectral hounds and a ghostly judge, the concept of a five year old girl condemned to forced isolation is enough to raise a few hairs on the back of anyone’s neck.

Today the room has been converted into a memorial for Ruth Carpenter and Laurie Dumas had started a nonprofit organization in her name which brings toys, puzzles and other comforts to disabled children in West Warwick schools.

While we have no evidence of her exact ailment or consequent treatment during her brief life, certainly no evidence of a mallet-wielding father whose pride drove him to unimaginable cruelty, speculation based on her nearly invisible existence sparks a certain profound sadness regardless. In truth, we’ll never know what afflicted Ruth or how she met her end and that in itself might be the real tragedy of her story; because no child deserves to be forgotten.

Defending the Devil

As impossible as it may seem to justify the alleged behaviour of Judge Job Carpenter, the true horror that is touched upon by ‘The Disappointments Room’ and it’s real-life counterpart goes much deeper and is far more unsettling. Taking a step back from what we know of Ruth Carpenter and the small attic room in Rhode Island, we look at the broader picture of mental and physical disability at the turn of the century.

Care for the disabled during the period of Ruth’s life fell into one of two categories: neglect or outright abuse. The alternative to home care was sanatoriums or mental wards. Apart from rampant overcrowding, under qualified staffing and a lack of proper facilities, there are innumerable evidenced accounts of abuse and borderline torture of patients. The conditions and treatment in early mental units were deplorable at best and more often than not physically sickening. Go to a horror convention and throw a tennis ball in any direction and you’ll hit three people with scripts that are set in an asylum – there’s a reason for that. So while I don’t feel the need to expand upon the obvious, I do feel I should point out the lesser known legalities that existed at the time.

Starting in 1867 in San Francisco, CA, ordinances were enacted into law preventing the disabled from appearing in public. While rolled into laws regarding panhandling, the popularity of the laws grew and by 1885, the year of Ruth Carpenter’s birth, were widespread across the United States. Conventionally known as ‘Ugly Laws’ they allowed for the fining or incarceration of those with disabilities who were present in public places or settings. An example of these Ugly Laws comes from Chicago, which reads in part:

“Any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, or an improper person to be allowed in or on the streets, highways, thoroughfares, or public places in the city, shall not therein or thereon expose himself to public view, under penalty of a fine of $1 for each offense (Chicago City Code 1881)”

If indeed Ruth Carpenter was born with a disability or disfigurement, as implied by Laurie Dumas’ account, it’s entirely possible she wasn’t legally allowed to be in public. Her father, a Judge, would be well aware of these ordinances and the consequences of violation which often included mandatory institutionalization at one of the aforementioned horror facilities.

Even more shocking is that these Ugly Laws not only encompassed entire states, such as Pennsylvania, but they remained on the books and actively enforced until the mid 1970’s, even after the signing of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. It wasn’t until the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 when protection of rights and a standard of treatment was finally legally adopted in the United States.

During the time of the Carpenters, A child with a disability wasn’t just a source of shame as portrayed in regards to the fictional Judge Blacker’s motivations, it was an actual legal and logistical nightmare. Arguably, home care such as a ‘disappointments room’ was a better and more compassionate alternative to both public and private sanatoriums and the level of care they provided. While isolation from society in many places wasn’t optional, it was mandatory.

To be able to make a case that the alleged actions of Judge Carpenter, shuttering away his daughter in a room at home for the entirety of her young life, may have actually been the most humane and kind form of treatment she could expect at that period in time is disgusting. Yet sadly, that’s what really breaks my heart about the themes and story of ‘The Disappointment Room’.

The reality of this film and the scope of what can be drawn from it are the true disappointments: a systematic failure to provide proper care for those in need and to protect them from the discrimination and abuse which spanned the better part of a century (just legally speaking).

The story of Ruth Carpenter, a child nearly forgotten, is just one in a mosaic of victims lost to this system which the common people endorsed and supported. And that my friends, is actually scary.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews