SYNOPSIS:

After the group suicide of four people, journalists Yuu and Rie investigate the reasons behind an endless cycle of suicides, blamed on an infamous Suicide Manual, hidden in a tag-less DVD disk. Said manual is shot in an infomercial fashion, with examples of the best methods to kill yourself and demonstrations by real people. When investigating further, Yuu and Rie find out that in Buddhist beliefs, when a person kills himself, he or she is sent to a certain hell, from which they induce other people to commit suicide. But is this what is really happening?

REVIEW:

And now, a real conversation had between my husband and I:

HUSBAND: What are you watching?

ME: One of my assignments. It’s called Suicide Manual.

HUSBAND: …Japanese?

ME: How did you guess?

I’ve spoken before about the intricate history connected to suicide in Japan (see the review for Noriko’s Dinner Table), but even without doing the research, it’s an unfortunate cliché that Japanese people are—how do I put this?—more “accepting” of suicide compared to Americans. It’s not as if suicide is encouraged—quite the contrary–but it is such a highly publicized and tragically common part of the culture that it isn’t hard to find support groups on either side of the problem.

In 1993, a book called The Complete Manual of Suicide was released in Japan to decidedly mixed reception. Wataru Tsurumi’s guide is does not directly advocate for suicide, but it also doesn’t go out of its way to suggest seeking healthier options either. The book’s clearly stated purpose is to weigh the pros and cons between various methods, based on pain scale and rate of success. It was obviously controversial at the time of release and still is today, but it was popular, especially among the under-thirty demographic. And there is something to be said for the “nobility” of the person who respects your right to want to take your own life. A depressed, lonely individual who expresses their desires is usually met with words of encouragement that often ring hollow—if you are serious about dying, the phrase “there’s so much to live for” likely holds little value. Imagine the perverse comfort of discovering someone who will not only hear you out, but even help you plan your own death.

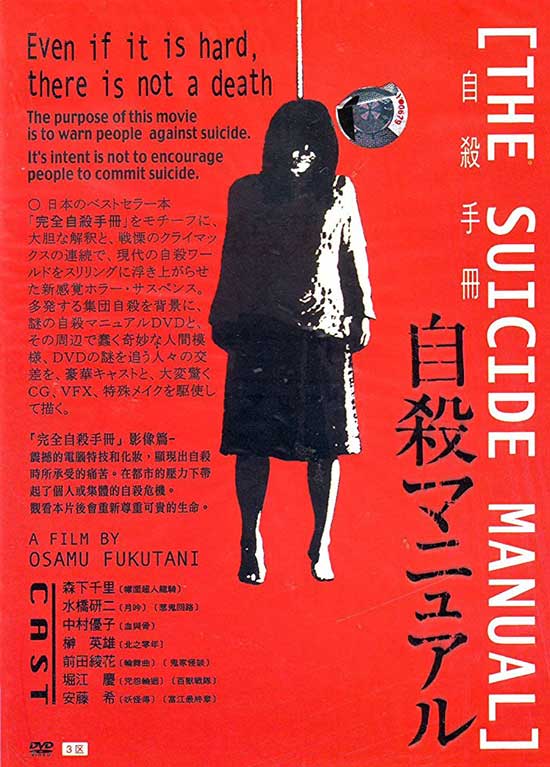

The film Suicide Manual only takes slight inspiration from Tsurumi’s book, more in spirit than a direct adaptation (the only mention of the book is a partially obscured flash of the cover during the opening credits). Like the book, it sets its disclaimers right out front: “The purpose of this movie is to warn people about suicide.” This expresses the filmmaker’s sensitivity towards the issue, their direct intent to not be involved in any lawsuits down the line–then the film immediately cuts to the aftermath of a suicide pact. It’s hard not to find this just a smidge exploitative, as this very serious and sad subject eventually spirals into a ripoff of Ringu.

Yuu is a sullen cameraman working for a TV station that thrives off juicy stories about human misery, and he is swiftly assigned a project centered on the recent group suicide in a local apartment. Yuu reluctantly pursues the story, with his pretty assistant Rie in tow. They encounter a depressed schoolgirl named Nanami skulking around the crime scene, and she introduces them to the Suicide Manual: a black box DVD whose creator is only known as Rickie.

According to Nanami, Rickie is an active presence on an online suicide message board and if she senses that a user is serious enough, she sends them a copy of her homemade how-to guide. The DVD is a concise and practical guide (with admittedly beautiful production values) to the most popular forms of suicide, hosted by Rickie herself. Lovely, level-headed Rickie guides us through a graphic demonstration of each method, from the history behind the noose to the more exotic suicide machines. She becomes something of an idol among users; most express an almost cultlike devotion to die with Rickie herself.

Upon watching the DVD, the video begins to creep into Yuu’s subconscious and drives him deeper into reclusive obsession. As the pieces of the puzzle surrounding Rickie come together, we realize that nothing is quite what it seems and that the video is actually spreading a virus to its watchers, almost as if they’re being possessed.

Like I said, this film takes a very delicate subject and twists it into a ghost story (and kind of a silly one at that) in the last act, so it’s hard to take its sensitive disclaimers very seriously–as if the threat of spooky scary spirits would make anyone change their mind about killing themselves. But it’s also hard to say that the film isn’t uniquely sympathetic to its cause, as the suicidal characters (namely Nanami) are painted as self-aware, introspective, and even brave compared to our “healthier” characters.

Rickie’s DVD is quite artistic and well-produced; with moody lighting, elegant staging, and a calm beautiful host speaking of each process with practicality and even poetry, harshly juxtaposed against the darkness of its subject. It sort of speaks to the draw of suicide, a perverse romanticizing of something terrible, which is nothing new to the internet age (flip through a Norton anthology of literature, you’ll find something). It’s sickening and sad how lovely it can all look when considered through a damaged point of view. Still, the film makes its morals quite clear, with plenty of characters outright saying “Never kill yourself” and frequent warnings of the hellish afterlife that awaits suicides.

It’s hard to be both sensitive to a major societal problem while coming from a place of journalistic neutrality (whatever that is), so I would like to take a moment to apologize to anyone who may have been offended by any of my wording in this review. It’s a tricky subject, to put it mildly, but it is nice(?) to see something that doesn’t treat suicidal people as ticking time bombs or diseased Faberge eggs that will jump off a building at the slightest provocation. These are dangerously sad people, but that shouldn’t mean that they’re completely unhinged with no perspective on reality. Perhaps the problem is too much perspective, too much self-awareness. Even in this technological age where we are more connected than we’ve ever been, it is especially devastating to still feel lonely. Maybe, someone simply willing to listen no matter how dark your thoughts, is enough of a lifeline to keep you hanging on.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews