SYNOPSIS:

In the early 18th century a plowman unearths a skeleton that is neither man nor beast. He reports his discovery to a visiting judge, but the carcass mysteriously vanishes before it can be examined. Within hours evil manifestations begin to sweep through the small village as the resurrected entity grows stronger. Some of the villagers disappear into the woods, where they revert to the old ways of paganism and human sacrifice.

REVIEW:

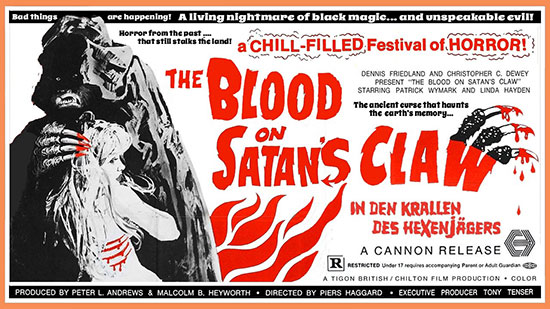

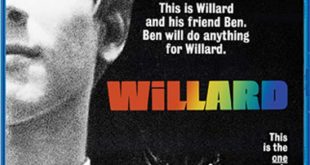

During the sixties and seventies two studios kept a stranglehold on the British horror film market. Hammer Films ruled the gothic arena with their moody and increasingly explicit films, while the competing Amicus Films freely raided Hammer’s stable of directors and stars for anthology films like 1972’s Tales from the Crypt. But there was another studio lurking in the shadows— a smaller outfit named Tigon British Film Productions, eager to bite off their own piece of the horror market. Founded by producer Tony Tensor, Tigon Films struggled with lower budgets than Hammer and Amicus, but their combination of creativity and moxie produced some memorable films. The jewel in Tigon’s crown was Michael Reeves’ 1968 classic Witchfinder General. Reeves became Tigon’s fair-haired boy and seemed destined for cinematic glory, until he died of a drug overdose during preproduction on The Oblong Box (1968). Two years after Reeves’ demise Tigon tried to recapture Witchfinder General’s success with 1971’s SATAN’S SKIN, released in the USA as BLOOD ON SATAN’S CLAW, or The Blood on Satan’s Claw if you like unnecessary articles in your titles.

Though it never reaches Witchfinder’s iconoclastic heights, Blood on Satan’s Claw stands as a memorable and entirely original tale of demonic possession and religious repression. In Witchfinder General corrupt men invoked God’s name to remorselessly brutalize the innocent. Blood on Satan’s Claw is the polar opposite, wherein the embodiment of sin seduces innocent villagers who, after enduring lives of repressed piety, are helpless to resist its spell.

Our setting is an early 18th century British farming village. Ralph, a young farmhand, unearths a rotting carcass of some demonic creature. He alerts a visiting judge, but when the magistrate arrives the cadaver has mysteriously vanished. The judge quickly dismisses the discovery as mere rural superstition, but within hours the unearthed demon begins to manifest its evil on the innocent village. A visiting woman suffers a nervous breakdown after seeing the demon while another young man slices his own hand off during a hallucinatory vision. The evil spreads, drawing the local youth to form a pagan tribe that conducts fertility rites and human sacrifice. The wise judge finally puts aside his scientific ways and admits they are facing the supernatural. But it may already be too late to save the village.

Blood on Satan’s Claw is an intriguing example of a director and producer balancing conflicting visions of art and commerce. The film’s producer, Tony Tensor, had cut his teeth on British sexploitation films, quickly building a reputation as a no frills cost cutter. But Tensor also had an eye for new talent, including director Michael Reeves to whom he handed the reins of The Sorcerers (1967) and Witchfinder General. After Reeves’ untimely demise Tensor turned to Director Piers Haggard—an up-and-coming talent who’d trained at the prestigious National Theatre before directing acclaimed dramas for the BBC. Tensor wanted a rough and ready exploitation film, while Haggard was more interested in the film’s characters and rural setting than its graphic horror elements. After some initial disputes Tensor wisely stepped back, allowing his highbrow director to have his way so long as he included certain horrific and sexual elements. Haggard worked closely with screenwriter Robert Wynn-Simmons, crafting more nuanced characters than found in competing Hammer productions.

The result is an intelligent, sometimes shocking, film boasting refined characters and a perfectly realized vision of 18th century agrarian life. As the local judge Patrick Wymark (in his final role) shines, balancing the pompousness of his social rank with a sincere desire to serve the people. Likewise Reverend Fallowfield’s (Anthony Ainley) devotion to his flock feels genuine, if occasionally misguided. Popular sex comedy starlet Linda Hayden (Confessions of a Window Cleaner) gives an outstanding performance as the rebellious Angel Blake, proving to the world what she could do with a good script. Above all, the relationship between young lovers Ralph and Margaret is naïve and charming, making her terrible fate all the more tragic.

Speaking of tragic fates, Haggard never shies away from violence and sex, but his intelligent script keeps Satan’s Claw from slipping into pure exploitation. Angel Blake’s attempted seduction of Reverend Fallowfield is a great example of his literary balancing act. Linda Hayden’s nudity is certainly provocative but Haggard focuses on the tension generated by the reverend’s sexual repression. Angel is beautiful, willing and (by the sketchy standards of the day) of legal age. But our man of the cloth is so repulsed by the concept of a seductress that he banishes her from the church rather than attempt to battle his temptations. The film is packed with these intriguing conflicts of good vs. evil and sin vs. free will.

Haggard’s attention to detail extended to the film’s visuals. His team does an admirable job of recreating an 18th century agrarian community. Every frame features grain or livestock, underscoring how, despite the villagers’ Calvinistic virtues, the old religion (paganism) lurks just below the soil. Allusions to the ancient religion are everywhere; even Reverend Fallowfield’s name evokes the pagans’ love of mother earth more than Christianity. The village’s descent into paganism employs some clever, almost theatrical makeup and costuming, particularly Angel’s drawn on charcoal eyebrows and headdress. Talented cinematographer Dick Bush, who went on to lens Saul Bass’ remarkable Phase IV (1974) as well as Ken Russell’s Tommy (1975) and Lair of the White Worm (1988), bolstered Haggard’s creative vision.

Blood on Satan’s Claw isn’t prefect by any means. At times its pace feels languid and the shift from intimate character study to mass demonic possession feels a bit rushed. But these are minor complaints. Overall the film respects your intelligence while delivering plenty of ghoulish chills and for that it deserves a higher ranking in the pantheon of British horror films. I suggest putting it on your movie shelf right between those supernatural classics Night of the Demon (1957) and The Wicker Man (1973).

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Some of the problems in the script, the way seemingly important characters disappear and are never mentioned again, are because the movie was originally supposed to tell three seperate stories, then that idea was scrapped and they were all hastily combined into one.