SYNOPSIS:

“US army Major John Reisman, based in London, is an inventive man who often thinks outside the box which causes many problems in the structured military. But it is because of this mentality that in March 1944, he is assigned, or as his superiors put it volunteers for a near suicide mission. Prior to the Allied forces invading continental Europe, he and his team, who he will train personally with Sergeant Bowren as his second in command, will infiltrate a highly fortified and guarded French château being used by the Nazis as respite house and meeting place primarily for high ranking German officers, kill as many of the officers as possible and take out the communications tower. His squad will consist of twelve of the most heavily sentenced GI convicts, many whose sentence is death. Reisman, who doesn’t like the assignment because of the involvement of the convicts, adds one caveat to doing this job: that the convicts have their sentences commuted if they survive. Reisman quickly learns that besides a resentment to authority, the twelve convicts are a disparate group, each with their own button issues and motivations. Reisman not only has to get them to cooperate, but work as a team, which includes having a zero tolerance policy for the group as a whole on issues such as escape attempts while under his command. Even if he can achieve these goals, Reisman also faces the obstacle of Colonel Everett Breed, who is the antithesis of Reisman and who will be at the parachute training base at the same time as Reisman’s squad, for which Breed has disdain.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

David Ayer, director of the recent Warner Brothers release Suicide Squad (2016), described his film as ‘The Dirty Dozen with super-villains’ and cited the original movie as his primary inspiration. Made half a century ago, Robert Aldrich‘s war adventure is undoubtedly one of the most influential films ever produced. For the duration of World War II and for the decade that followed it, Hollywood helped to create an ideologically unified United States of America. It was ‘Us’ versus ‘Them’ or, as John Wayne might say, “They started it, now we’re going to finish it.” Through printed media, radio, movies, advertising and public service announcements, Americans were exposed to a steady diet of war propaganda – well-crafted persuasive messages designed to raise spirits, engender national pride and foster understanding of the reasons for going to war and of America’s inevitable victory. But by the late sixties, the messages emanating from Hollywood were very different.

The Korean War, the never-ending standoff between NATO and the Soviet Bloc, and the Vietnam stalemate made it powerfully clear to a generation of Americans that simple-minded jingoism and notions of a ‘moral war’ were no longer applicable. Everyone knew that war was hell, but it was also becoming obvious that there was nothing particularly ‘character-building’ about it either. Some films of the period began to portray the absurdity of war – The Bridge On The River Kwai (1957) and Paths Of Glory (1957) – while others satirised its insanity – Dr. Strangelove (1964) and Catch 22 (1970). Fact-based historical or biographical epics such as The Longest Day (1962), Battle Of The Bulge (1965), Patton (1970) and the Japanese-American co-production Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) were more simplistic but all reflected the sheer waste of war as well as its complexity. Another genre also appeared around the same time, the ‘All-Star War Buddy Film’ typically with large groups of famous actors bonding together in exciting wartime situations. The Guns Of Navarone (1961) started the trend, quickly followed by The Great Escape (1963), but it was The Dirty Dozen (1967) that set the template for years to come.

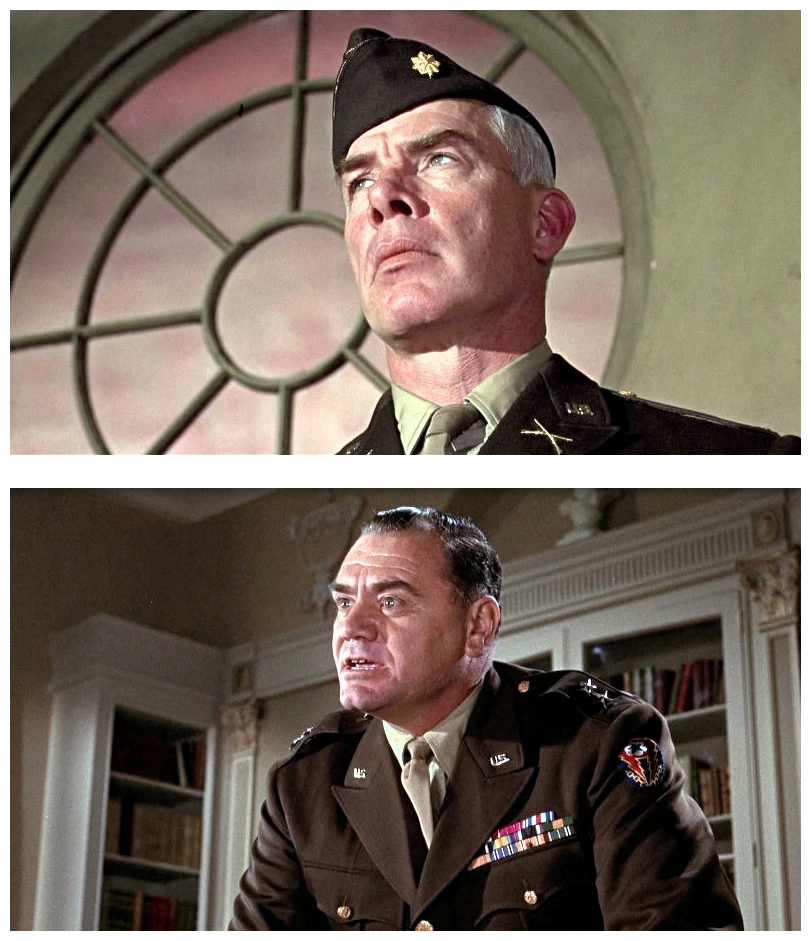

Based on the novel by E.M. Nathanson, The Dirty Dozen has no basis in historical fact (even though much has been written about something similar actually occurring during World War II) and although it’s not often thought of as such, became the first major mainstream film to acknowledge that brutality and atrocities occurred on both sides. “Damn them or praise them, you’ll never forget them!” blurbed the posters. It’s 1944 and D-Day is approaching. In addition to the Normandy invasion plan, the US military has come up with an auxiliary mission designed to break the German chain of command. Major John Reisman (Lee Marvin) must train a group of twelve convicted sociopaths, murderers and rapists to raid a secluded mansion where high-ranking German officers billet to meet their mistresses. If the ‘volunteers’ survive, their sentences will be commuted. As Reisman callously states: “There’s a good chance some of you won’t be coming back, so let’s not get all squawky about it.”

With minimum hand-wringing and no ‘true story’ to be faithful to, The Dirty Dozen is one of those war epics where one can just kick back and wallow in its amorality, free of conscience and consequences. While it certainly acknowledges that war is indeed hell, the rampant cynicism and negative tone throughout more or less suggests that, well, so is everything else, get used to it. Not the most noble of messages, but one that makes for an undeniably raucous action-packed and often exhilarating 150 minutes. Arriving in cinemas in the midst of the increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam, it’s easy to see how this aspect of the story might make an impact on some viewers. In depicting Allied soldiers as something less than model citizens, The Dirty Dozen broke a barrier, blurring the lines between the good guys and the bad guys. It was also one of the first movies to show the darker side of war, that the best soldiers are often society’s outcasts.

War is not civilised, and there’s no place for order or manners amidst the carnage of a battlefield. Despite the heroic musical score by Frank De Vol and unrelenting machismo evident throughout the film, the climactic shoot-out is more of a massacre than a battle. That being said, Aldrich didn’t want to make a ‘message’ movie. He liked the grittiness of the idea and appreciated that Nunnally Johnson‘s screenplay was a new approach to a World War II scenario but, from the outset, he intended the film to be a rousing adventure story. At its core, The Dirty Dozen is about camaraderie and how even the most unlikely men can, when placed in extreme circumstances, act valiantly. If it was directed by, say, Oliver Stone, the same story might come across as a blistering anti-war motion picture but, in this case, it’s a straightforward action-adventure tale for the masses. There is substance to be found, but only for those who could be bothered looking for it.

Unlike today’s war films which seem positively hellbent on depicting in clinical detail the waste of life and the horrendous mental and physical effects of war (presumably in penance for Hollywood’s usually frivolous treatment of the subject), this fictional tale manages to have its cake and eat it too. The masterstroke here is essentially not having any good guys. The Dirty Dozen represents the high point of Aldrich’s three-decade career as a filmmaker. Although two of his earlier movies – The Big Knife (1955) and Attack (1956) – garnered more critical acclaim, none of his directorial efforts met with the public reaction of The Dirty Dozen, and none has had a more lasting impact on popular culture and cinema. In Sleepless In Seattle (1993), when Tom Hanks is asked what the ultimate ‘guy’ movie is, he invokes The Dirty Dozen. Before they joined the ranks of The Dirty Dozen, many of the supporting actors were not as well known as they would become.

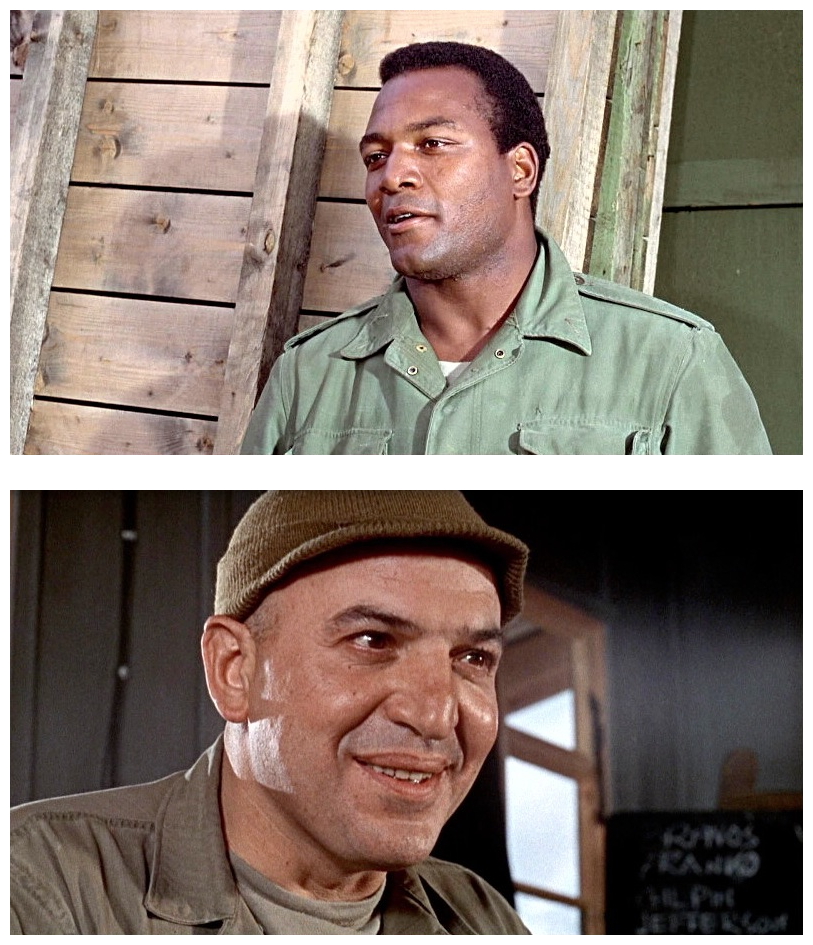

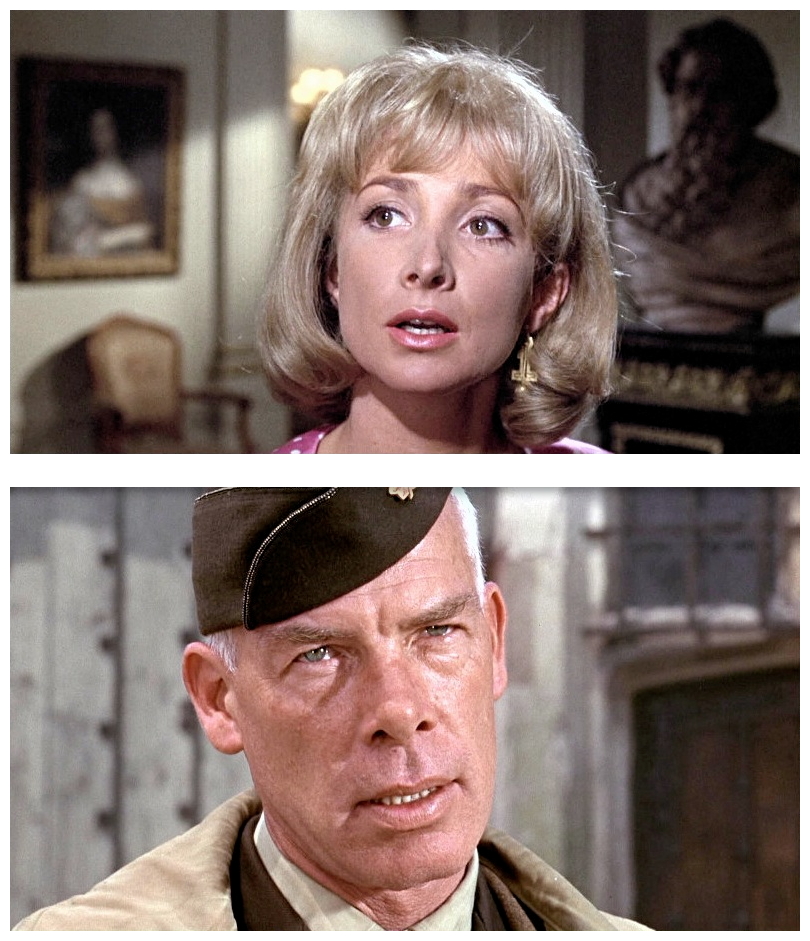

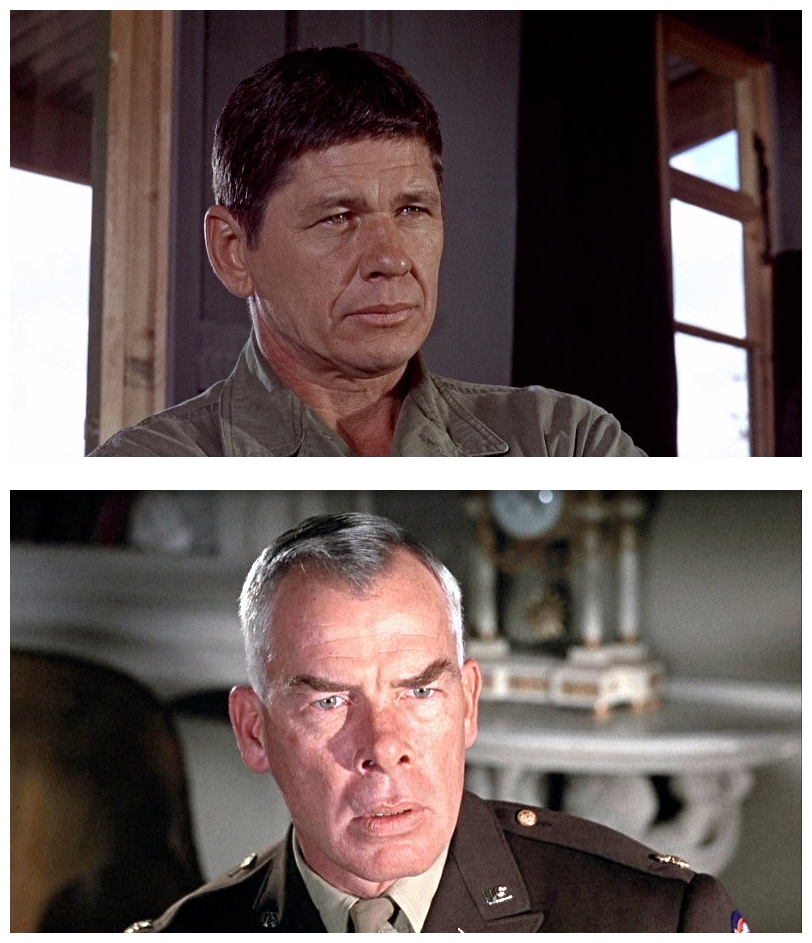

Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine and George Kennedy were recognised stars, and Charles Bronson had a solid catalogue behind him (although his biggest films were yet to come). Jim Brown was at the beginning of his career, John Cassavetes was relatively unknown, Telly Savalas had not yet become Kojak, and Donald Sutherland was still wet behind the ears. The Dirty Dozen opened doors for many of its cast members. Nearly everyone, except perhaps the most obscure members of the troupe, found it easier to get work after the film’s hugely successful run (US$45 million return on a US$5 million budget). Unfortunately, being an Aldrich production, women are given short shrift, their roles largely relegated to playing prostitutes or victims, but it’s worth remembering this was shortly after he had made Whatever Happened To Baby Jane? (1962) and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte (1964). Who could blame him after working with Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Olivia de Havilland and Agnes Moorehead?

Three years after The Dirty Dozen was released, Too Late The Hero (1970), also directed by Aldrich, was considered by many to be a sequel-of-sorts. Play Dirty (1969) starring Michael Caine also concerns convicts being recruited as soldiers, and the Italian film The Inglorious Bastards (1977) is a loose remake of The Dirty Dozen which, in turn, inspired Quentin Tarantino‘s Inglourious Basterds (2009). Several made-for-television movies were produced in the eighties which capitalised on the popularity of the first film. Marvin and Borgnine reprised their roles for The Dirty Dozen: The Next Mission (1985), commanding a group of military convicts in a mission to kill a German general who is plotting to assassinate Adolf Hitler. In The Dirty Dozen: The Deadly Mission (1987), Borgnine returns as General Worden but Telly Savalas, who had played the psychotic Maggot in the original film, plays a totally different character named Major Wright. Together they lead a team of military convicts to extract a number of German scientists who are being forced to make a deadly nerve gas.

In The Dirty Dozen: The Fatal Mission (1988) Savalas and Borgnine return to lead a group of renegade soldiers attempting to prevent a group of extreme German generals from starting a Fourth Reich. These tele-movies proved popular enough to commission an ongoing television show. Dirty Dozen: The Series (1988) was filmed in Yugoslavia starring Ben Murphy and John Slattery, and guest-starred a number of British actors including Ian McShane and Shane Rimmer. Unfortunately, the show lasted only eleven episodes before being cancelled, not even enough to go into syndication, which is why it has been rarely seen since. In the wake of The Dirty Dozen, a number of films went on to portray war and warriors in a more realistic and less glamorous fashion, and director Brian G. Hutton‘s Kelly’s Heroes (1970) owes much to Aldrich’s vision. Written by Troy Kennedy Martin, Kelly’s Heroes stars Clint Eastwood as an army lieutenant looking for a little something to tide him over after the war, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll make my farewells, and eagerly anticipate having your company again next week when I discuss another glorious anti-classic shoplifted from the bargain-basement remainders bin for…Horror News! Toodles!

The Dirty Dozen (1967)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews