SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

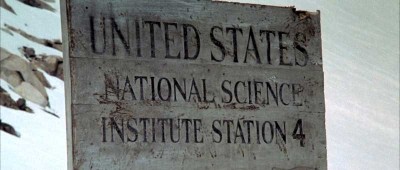

“In the midst of the Antarctic snow-field, the scientists and workers of a small American research base are shocked when a helicopter begins to circle their camp, chasing and shooting at a dog. When the helicopter is destroyed and the passenger’s are killed by accident, the dog is let into the base and the American’s begin to wonder what has actually happened. The helicopter is discovered to be of Norwegian make, and probably linked to the Norwegian base not too far from their own. Helicopter pilot J.R MacReady offers to travel to the Norwegian base and find out what has happened. On arrival, he finds that the place has been totally destroyed. He also discovers a mangled body that looks as though it was once that of a person, which he brings back with him to study. It is only then that the clues begin to add up, and the dog morphs horribly into a strange creature that attacks the researchers. They manage to fight it off, but the base doctor has come to a conclusion: An alien with the power to transform and take the appearance of anybody else is amongst them. Who is infected already, and who can be trusted? J.R MacReady sets out to find the answers to exactly that.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Born in 1948, director John Carpenter was considered one of the new generation of young filmmakers to come out of film school, the same school as George Lucas and so many others that found fame in the seventies. Though his first feature, Dark Star (1974), which was actually an expanded form of his film-school thesis, was well-received, especially at festivals and conventions. It was years before it gained any sort of wide distribution, and he did not become generally known to the public until Halloween (1978) and The Fog (1979). In 1981 John Carpenter returned to his first best genre, science fiction, with Escape From New York (1981). Tremendously good fun, it was nevertheless a disappointment, for by now people were expecting remarkable things with each new Carpenter film.

Life began to look even grimmer for John after his next film in 1982, a remake of Howard Hawks’ production of The Thing From Another World (1951). Although It didn’t completely flop at the box office, it was not the success that Universal needed to recoup the production costs, which were said to be around US$15 million. However, The Thing (1982) also known as John Carpenter’s The Thing, has since proven to be one of the great milestones in fantastic cinema, and its comparative failure at the box office could be a testament to its breaking of new ground. Mainstream audiences may well have been puzzled by the story (which was far more sophisticated than that of most filmed science fiction), and they were certainly revolted by the awesomely disgusting special effects. But these effects (the monstrous guises adopted by the ‘thing’) were not merely a grotesque icing on the cake, no. They were integral to the story.

Life began to look even grimmer for John after his next film in 1982, a remake of Howard Hawks’ production of The Thing From Another World (1951). Although It didn’t completely flop at the box office, it was not the success that Universal needed to recoup the production costs, which were said to be around US$15 million. However, The Thing (1982) also known as John Carpenter’s The Thing, has since proven to be one of the great milestones in fantastic cinema, and its comparative failure at the box office could be a testament to its breaking of new ground. Mainstream audiences may well have been puzzled by the story (which was far more sophisticated than that of most filmed science fiction), and they were certainly revolted by the awesomely disgusting special effects. But these effects (the monstrous guises adopted by the ‘thing’) were not merely a grotesque icing on the cake, no. They were integral to the story.

The original film of The Thing is an acknowledged classic, but has possibly been over-praised. Certainly it jettisoned the most interesting element of the story on which it was based, that the ‘thing’ (which has apparently been frozen in the Antarctic for millions of years) has the capacity to mimic exactly any life form it is able to absorb. It was one the first in a series of science fiction ‘shape-shifters’ that had seldom found their way into movies, although they did appear in the science fiction film John loved as a youth: It Came From Outer Space (1953). Anyway, the Hawks movie reduced The Thing to a bloodsucking carrot, but John and his screenwriter Bill Lancaster (son of actor Burt) stayed close to the original story.

The original film of The Thing is an acknowledged classic, but has possibly been over-praised. Certainly it jettisoned the most interesting element of the story on which it was based, that the ‘thing’ (which has apparently been frozen in the Antarctic for millions of years) has the capacity to mimic exactly any life form it is able to absorb. It was one the first in a series of science fiction ‘shape-shifters’ that had seldom found their way into movies, although they did appear in the science fiction film John loved as a youth: It Came From Outer Space (1953). Anyway, the Hawks movie reduced The Thing to a bloodsucking carrot, but John and his screenwriter Bill Lancaster (son of actor Burt) stayed close to the original story.

The film is an abject lesson in building tension and atmosphere economically. It opens with a beautifully photographed scene of a husky fleeing across the snow, being pursued by a Norwegian helicopter trying to shoot it. It makes its way to an American research base. Why are the Norwegians trying to kill the nice doggie? We are instantly hooked. Building slowly, but giving extraordinary value when it reaches its climaxes, the film goes on from this mysterious opening to detail the slow growth of the horror of loss of personality, and of alienation from those close to you. It is a recognised nightmare of small children that a friend or parent appears alien, distant, a thing without a face. The ‘thing’ begins taking everybody over, and there seems to be no way of knowing who is real and who is a monstrous replica built out of the ‘thing’s protoplasmic ability to look like anything at all, and its undoubted intelligence.

The film is an abject lesson in building tension and atmosphere economically. It opens with a beautifully photographed scene of a husky fleeing across the snow, being pursued by a Norwegian helicopter trying to shoot it. It makes its way to an American research base. Why are the Norwegians trying to kill the nice doggie? We are instantly hooked. Building slowly, but giving extraordinary value when it reaches its climaxes, the film goes on from this mysterious opening to detail the slow growth of the horror of loss of personality, and of alienation from those close to you. It is a recognised nightmare of small children that a friend or parent appears alien, distant, a thing without a face. The ‘thing’ begins taking everybody over, and there seems to be no way of knowing who is real and who is a monstrous replica built out of the ‘thing’s protoplasmic ability to look like anything at all, and its undoubted intelligence.

Its various overt manifestations (in the first instance the nice doggie is turned literally inside-out, hissing, spitting, oozing, sprouting wildly whipping tentacles) are quite extraordinary, but they are never allowed to dominate the basic situation of a group of ordinary men trapped in a nightmare. That is, the film (as in Hawks’ original) gives due credit to humanness as well as monstrosity. But so bizarre is the ‘thing’ that many viewers could see no further, which may be why the film was not instantly recognised as the undoubted classic it is.

Rob Bottin, a young make-up artist who had also worked with Carpenter on The Fog, performed miracles with his large team of technicians, in creating the various effects. Most spectacular perhaps is the moment when electrodes are applied to a recent corpse in the attempt to stimulate a heartbeat. Suddenly the body’s torso grows teeth and bites the doctor’s arms off, it’s neck stretches obscenely and lowers the corpse’s head to the floor. Its head extrudes an enormously long tongue which whips around a table leg and pulls itself along, then it grows legs like a spider and scuttles away. One of the characters speaks surely for the audience as well when he looks aghast at one of the ‘thing’s incarnations and says (quite in character) “You gotta be f*ckin’ kidding me…”

Rob Bottin, a young make-up artist who had also worked with Carpenter on The Fog, performed miracles with his large team of technicians, in creating the various effects. Most spectacular perhaps is the moment when electrodes are applied to a recent corpse in the attempt to stimulate a heartbeat. Suddenly the body’s torso grows teeth and bites the doctor’s arms off, it’s neck stretches obscenely and lowers the corpse’s head to the floor. Its head extrudes an enormously long tongue which whips around a table leg and pulls itself along, then it grows legs like a spider and scuttles away. One of the characters speaks surely for the audience as well when he looks aghast at one of the ‘thing’s incarnations and says (quite in character) “You gotta be f*ckin’ kidding me…”

John’s specialty has always been to capture the feelings of groups (sometimes individuals) who are trapped and isolated. This could, if repeated often enough, be both gloomy and paranoid, except that he is also excellent at showing courage and level-headedness in extremis, so his films are not particularly downbeat. The Thing, which ends with two survivors too exhausted to care anymore if one or the other is actually the monster (a terrible thought is that it could be both), is not exactly cheerful, yet they have survived, and there is something touching about this momentary camaraderie in front of a hellish scene of flames licking in the snow. John Carpenter is a genuine auteur, although his films do not have the unmistakable style of, say, a Cronenberg, or even the unmistakable themes of, say, a Spielberg. He always emphasises narration, using an unobtrusively fluid camera style and tight editing. He has also composed the music for most of his films, but in the case of The Thing, John awarded the scoring duties to the ever-dependable Ennio Morricone, whose suitably nerve-racking, repetitive soundtrack twangs of John’s earlier compositions.

John’s specialty has always been to capture the feelings of groups (sometimes individuals) who are trapped and isolated. This could, if repeated often enough, be both gloomy and paranoid, except that he is also excellent at showing courage and level-headedness in extremis, so his films are not particularly downbeat. The Thing, which ends with two survivors too exhausted to care anymore if one or the other is actually the monster (a terrible thought is that it could be both), is not exactly cheerful, yet they have survived, and there is something touching about this momentary camaraderie in front of a hellish scene of flames licking in the snow. John Carpenter is a genuine auteur, although his films do not have the unmistakable style of, say, a Cronenberg, or even the unmistakable themes of, say, a Spielberg. He always emphasises narration, using an unobtrusively fluid camera style and tight editing. He has also composed the music for most of his films, but in the case of The Thing, John awarded the scoring duties to the ever-dependable Ennio Morricone, whose suitably nerve-racking, repetitive soundtrack twangs of John’s earlier compositions.

One final observation of John Carpenter may be a strength or a weakness, it’s hard to tell: He seems to be Manichean, which is to say he seems to believe in Evil as existing outside humanity, as an absolute force which has the same integrity as Good. In Christine (1983) he took away the possible psychological reasons for the car’s behaviour (infected by the nastiness of a previous owner, perhaps), and in a bravura opening sequence shows it wholly malicious while still on the assembly line. In John’s movies there is usually a Shape or a Thing, a malevolence out there waiting to get us. One of the paradoxes of fantastic cinema is that many of us want the catharsis of imagining ourselves being got, and there is one element of comfort in his films: While Evil may be formidable, it is not irresistible. John also believes in the strength of humans to cope with it. And it’s with that thought in mind I ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier with another feather from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News! Toodles!

One final observation of John Carpenter may be a strength or a weakness, it’s hard to tell: He seems to be Manichean, which is to say he seems to believe in Evil as existing outside humanity, as an absolute force which has the same integrity as Good. In Christine (1983) he took away the possible psychological reasons for the car’s behaviour (infected by the nastiness of a previous owner, perhaps), and in a bravura opening sequence shows it wholly malicious while still on the assembly line. In John’s movies there is usually a Shape or a Thing, a malevolence out there waiting to get us. One of the paradoxes of fantastic cinema is that many of us want the catharsis of imagining ourselves being got, and there is one element of comfort in his films: While Evil may be formidable, it is not irresistible. John also believes in the strength of humans to cope with it. And it’s with that thought in mind I ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to tickle your fear-fancier with another feather from that cinematic ugly duckling known as…Horror News! Toodles!

The Thing (1982)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews