SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

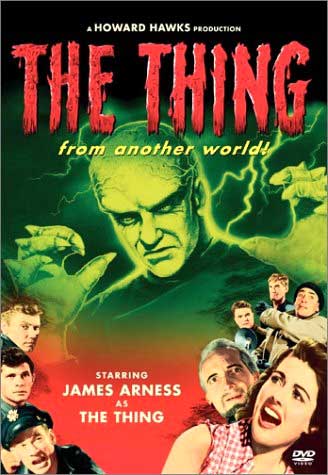

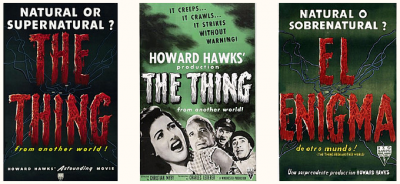

“Scientists at an Arctic research station discover a spacecraft buried in the ice. Upon closer examination, they discover the frozen pilot. All hell breaks loose when they take him back to their station and he is accidentally thawed out! Producer Howard Hawks’ adaptation of the John Campbell story of an arctic expedition that runs afoul of a blood sucking alien is often credited (or blamed) with launching the evil-monster-tries-to-destroy-humanity films that were so prevalent in the fifties.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

While Klaatu – the alien in The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) – was landing his flying saucer in the middle of Washington DC, another alien was being thawed-out with his saucer near the North Pole. Unlike Klaatu, this one did not have humanity’s best interests at heart. In fact, he didn’t even have a heart, being little more than a walking vegetable, albeit an intelligent and powerful one. He made his appearance in The Thing (1951), also known as The Thing From Another World, and his attitude towards mankind was to become typical of most extraterrestrial visitors on the screen during the fifties. As with so many of the films that established the main trends in science fiction cinema, The Thing is far superior to the various imitations that followed it.

Though the directing credit is officially Christian Nyby‘s, it is more-or-less common knowledge that the film was directed by one of Hollywood’s film-making aristocrats, Howard Hawks. Apparently Nyby, who had been the editor on many of Hawks’ films, wanted a directing credit for union reasons and Hawks kindly gave him this one. The film contains all the Hawks trademarks, in particular the overlapping dialogue of the actors. The film’s star, Kenneth Tobey, once told me “It takes a lot of rehearsal to get that unrehearsed quality.”

Though the directing credit is officially Christian Nyby‘s, it is more-or-less common knowledge that the film was directed by one of Hollywood’s film-making aristocrats, Howard Hawks. Apparently Nyby, who had been the editor on many of Hawks’ films, wanted a directing credit for union reasons and Hawks kindly gave him this one. The film contains all the Hawks trademarks, in particular the overlapping dialogue of the actors. The film’s star, Kenneth Tobey, once told me “It takes a lot of rehearsal to get that unrehearsed quality.”

Another major asset is the Charles Lederer screenplay. Lederer’s ability to write smart, crackling dialogue hadn’t diminished since he’d worked on the first screen version of The Front Page (1931). All the characters in The Thing, stock actors though they may be, breathe with a certain life of their own, a quality so often missing from other fifties science fiction films. Even the ‘love interest’ is handled with a certain amount of wit and style, its cliches made painless by an unusually talented director and writer. Serious science fiction fans tend to regard the film with disapproval and consider it a typical Hollywood treatment of a science fiction masterpiece, John W. Campbell‘s novella Who Goes There? published in Astounding Magazine in 1938. While Hawks’ film may not be perfect science fiction, it’s certainly a better-than-average science fiction film, and excellent cinema.

Another major asset is the Charles Lederer screenplay. Lederer’s ability to write smart, crackling dialogue hadn’t diminished since he’d worked on the first screen version of The Front Page (1931). All the characters in The Thing, stock actors though they may be, breathe with a certain life of their own, a quality so often missing from other fifties science fiction films. Even the ‘love interest’ is handled with a certain amount of wit and style, its cliches made painless by an unusually talented director and writer. Serious science fiction fans tend to regard the film with disapproval and consider it a typical Hollywood treatment of a science fiction masterpiece, John W. Campbell‘s novella Who Goes There? published in Astounding Magazine in 1938. While Hawks’ film may not be perfect science fiction, it’s certainly a better-than-average science fiction film, and excellent cinema.

The film begins with army pilot Captain Hendry (Kenneth Tobey) and his crew flying to a remote Arctic base where a number of scientists are holding a secret conference. En route his plane is diverted to a mysterious area in the snow where a great deal of magnetic activity has been detected. Investigation reveals a saucer-like object buried in the ice, but when an attempt is made to thaw the ice using thermite bombs the saucer explodes and the group are left with nothing but smoke until one of them notices another, smaller shape in the ice. A block of ice containing the titular ‘thing’ is chipped out and flown to the base where it arouses great excitement among the scientists, who divide into two separate groups, the one led by Doctor Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite) wants to defrost the creature immediately, while the opposing group warns that it may contain organisms dangerous to man and should be kept frozen for the time being.

The film begins with army pilot Captain Hendry (Kenneth Tobey) and his crew flying to a remote Arctic base where a number of scientists are holding a secret conference. En route his plane is diverted to a mysterious area in the snow where a great deal of magnetic activity has been detected. Investigation reveals a saucer-like object buried in the ice, but when an attempt is made to thaw the ice using thermite bombs the saucer explodes and the group are left with nothing but smoke until one of them notices another, smaller shape in the ice. A block of ice containing the titular ‘thing’ is chipped out and flown to the base where it arouses great excitement among the scientists, who divide into two separate groups, the one led by Doctor Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite) wants to defrost the creature immediately, while the opposing group warns that it may contain organisms dangerous to man and should be kept frozen for the time being.

However, the creature is inadvertently thawed due to a mistake with an electric blanket and immediately crashes out of the nearest window into the snow, where it is attacked by a pack of sled dogs. By the time the men reach the scene it has vanished, leaving behind an arm that had been torn off by the dogs. Examination of the limb reveals that the ‘thing’ isn’t an animal but a humanoid vegetable. The scientists also discover that in the palm of the thorny hand are a number of seeds which, if planted, will produce more ‘things’.

However, the creature is inadvertently thawed due to a mistake with an electric blanket and immediately crashes out of the nearest window into the snow, where it is attacked by a pack of sled dogs. By the time the men reach the scene it has vanished, leaving behind an arm that had been torn off by the dogs. Examination of the limb reveals that the ‘thing’ isn’t an animal but a humanoid vegetable. The scientists also discover that in the palm of the thorny hand are a number of seeds which, if planted, will produce more ‘things’.

Various attempts to destroy the monster fail miserably and the ‘thing’ successfully invades a section of the camp, turning its hothouse into a breeding ground for its seedling offspring, which it nourishes with human blood. Eventually, despite being hindered by Doctor Carrington and his followers who want to establish communication with the creature, Hendry and his men manage to destroy the alien by tricking it to stand on a high-voltage grid. Like one of the monsters from earlier ‘mad scientist’ films, it is consumed by flames. Mankind is saved, but only for the time being, claims reporter Ned Scott (Douglas Spencer) in a broadcast at the end of the film: “I bring you a warning – tell the world, tell this to everyone where ever they are – watch the skies!”

Various attempts to destroy the monster fail miserably and the ‘thing’ successfully invades a section of the camp, turning its hothouse into a breeding ground for its seedling offspring, which it nourishes with human blood. Eventually, despite being hindered by Doctor Carrington and his followers who want to establish communication with the creature, Hendry and his men manage to destroy the alien by tricking it to stand on a high-voltage grid. Like one of the monsters from earlier ‘mad scientist’ films, it is consumed by flames. Mankind is saved, but only for the time being, claims reporter Ned Scott (Douglas Spencer) in a broadcast at the end of the film: “I bring you a warning – tell the world, tell this to everyone where ever they are – watch the skies!”

In retrospect one wonders exactly what people were supposed to be watching for – flying saucers or Russian planes? With the ‘early warning’ associations of the Arctic setting, the film can easily be interpreted as a parable of anti-communist vigilance. Some critics have accused it of being a piece of pro-military, anti-science propaganda, an unjustified view as neither the military nor the scientists come out of it well. Hendry, who is ultimately triumphant over the monster, only succeeds when he abandons the army rule-book and uses his own common sense (after it’s been destroyed he receives a message from his superiors ordering him not to harm the creature). Some of the scientists are made to look foolish because they too are bound by a scientific rule-book of their own. As the ‘thing’ is intelligent they believe there has to be some common ground between it and them, but they’re wrong. Its species may be capable of building a spaceship, but that doesn’t automatically make it ‘reasonable’ in the human sense of the word. If the film is anti-anything, it’s anti-dogma.

In retrospect one wonders exactly what people were supposed to be watching for – flying saucers or Russian planes? With the ‘early warning’ associations of the Arctic setting, the film can easily be interpreted as a parable of anti-communist vigilance. Some critics have accused it of being a piece of pro-military, anti-science propaganda, an unjustified view as neither the military nor the scientists come out of it well. Hendry, who is ultimately triumphant over the monster, only succeeds when he abandons the army rule-book and uses his own common sense (after it’s been destroyed he receives a message from his superiors ordering him not to harm the creature). Some of the scientists are made to look foolish because they too are bound by a scientific rule-book of their own. As the ‘thing’ is intelligent they believe there has to be some common ground between it and them, but they’re wrong. Its species may be capable of building a spaceship, but that doesn’t automatically make it ‘reasonable’ in the human sense of the word. If the film is anti-anything, it’s anti-dogma.

As it happens, Campbell’s original concept would have made a more effective reflection of Cold War paranoia since his ‘thing’ was able to change it’s shape, becoming perfect replicas of their victims. Thus in his story the human survivors in the claustrophobic Arctic camp were unable to detect who was real and who wasn’t, something that had a real-life counterpart in the minds of many people at the time, which became the central theme of John Carpenter’s 1982 remake of the film. Even so, the film possesses a certain real horror of it’s own – the monster may have been made more substantial and less subversive, but thanks to Hawks’ skillful handling it is still a frightening creation. Early in the film a door is opened to briefly and unexpectedly reveal the snarling ‘thing’. For the rest of the film, whenever a door opens, the spectator instinctively flinches, the resulting build-up of tension is very effective.

As it happens, Campbell’s original concept would have made a more effective reflection of Cold War paranoia since his ‘thing’ was able to change it’s shape, becoming perfect replicas of their victims. Thus in his story the human survivors in the claustrophobic Arctic camp were unable to detect who was real and who wasn’t, something that had a real-life counterpart in the minds of many people at the time, which became the central theme of John Carpenter’s 1982 remake of the film. Even so, the film possesses a certain real horror of it’s own – the monster may have been made more substantial and less subversive, but thanks to Hawks’ skillful handling it is still a frightening creation. Early in the film a door is opened to briefly and unexpectedly reveal the snarling ‘thing’. For the rest of the film, whenever a door opens, the spectator instinctively flinches, the resulting build-up of tension is very effective.

The monster is also disturbing because it is intelligent. It is one thing to be faced with a rampaging mindless beast, but to be threatened by something superior yet utterly hostile to mankind induces a profoundly unsettling feeling akin to that which a child experiences when an adult is actively hostile towards them. It is also an insult to the ego. Like Pierce Brosnan’s optimistic scientist in Mars Attacks! (1998) we’d like to think that a superior intelligence from Out There would at least give us a condescending pat on the head in recognition of our meagre achievements, instead of contemptuously tossing us aside as the ‘thing’ does with Doctor Carrington when he approaches it ‘scientist-to-scientist’. And it’s with tossing in mind that I respectfully ask you to join me next week when I have the opportunity to give you another swift kick in the old brain-box with another fright-filled fear-fest from the far side of…Horror News! Toodles!

The monster is also disturbing because it is intelligent. It is one thing to be faced with a rampaging mindless beast, but to be threatened by something superior yet utterly hostile to mankind induces a profoundly unsettling feeling akin to that which a child experiences when an adult is actively hostile towards them. It is also an insult to the ego. Like Pierce Brosnan’s optimistic scientist in Mars Attacks! (1998) we’d like to think that a superior intelligence from Out There would at least give us a condescending pat on the head in recognition of our meagre achievements, instead of contemptuously tossing us aside as the ‘thing’ does with Doctor Carrington when he approaches it ‘scientist-to-scientist’. And it’s with tossing in mind that I respectfully ask you to join me next week when I have the opportunity to give you another swift kick in the old brain-box with another fright-filled fear-fest from the far side of…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Great review, Nigel! I hold this film in very high regard and your write up was spot on. I’ve reviewed it in the past and I think I will do some sort of essay on it in the future just to update it but your perspective mirrors mine very much. Especially the Cold War aspect. Awesome job!

Thanks for reading Vic! Many films of the fifties are reflections of their times, and none better than paranoid horror films disguised as sci-fi. This is also one time when I think the original and remake are just as good as each other, for very different reasons, of course. While I’m at it, I should say I really liked the prequel made in 2011 – although not as good or as well-made as the 1951 and 1982 versions, it’s still a very suitable, faithful prequel, its closing smoothly transitioning into the beginning of the 1982 version. Oh, one more thing (pun intended) – ever seen the 1973 made-for-TV movie A COLD NIGHT’S DEATH starring Robert Culp? It was a huge inspiration for John Carpenter when making The Thing, and it’s a damn clever little film. Recommended.