SYNOPSIS:

“Sherlock Holmes becomes involved in the case of Gabrielle Valladon when the young woman is fished out of the river and brought to 221b Baker Street by a cabbie. She’s quite beautiful and doesn’t really remember who she is or why she mentioned Holmes’ name when found. Using his deductive powers, Holmes determines she is Belgian and having retrieved her luggage from Victoria station, that she had only recently arrived on the boat train. She came to England looking for her husband and has no idea how she ended up in the river. Soon however, the case becomes more complex when Holmes’ brother Mycroft warns him to stay away and that it involves the security of realm. Undaunted, Holmes, Watson and Gabrielle follow the trail of clues and are soon in Inverness where they encounter both a troop of missing midgets – a case Holmes had earlier turned down – and have an encounter with the Loch Ness monster. Mycroft also has some unexpected information for his brother.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

On the 13th April 2016 the Guardian news website reported that the remains of a monster had actually been discovered at the bottom of Loch Ness! Unfortunately, it was only a model of the elusive beast and not the real thing. The ten-metre long model used in The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes (1970) was found 180 metres down by an underwater robot. Loch Ness expert Adrian Shine: “We have found a monster, but not the one many people might have expected. The model was built with a neck and two humps and taken alongside a pier for filming of portions of the film in 1969. The director did not want the humps and asked that they be removed, despite warnings I suspect from the rest of the production that this would affect its buoyancy. And the inevitable happened. The model sank.” Billy Wilder belongs to that select band of directors which includes Alfred Hitchcock, William Wyler, Ken Russell and David Lean, who became household names to the most mainstream of filmgoers. The Wilder stamp on a movie is recognised as the stamp of quality and, although he concentrated on comedy during the sixties, he was responsible for some of the best dramas ever made. His first film as director was The Major And The Minor (1942) and within a few years he scooped the Oscars with The Lost Weekend (1945) winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Screenplay.

Wilder’s catalogue drips with gems such as Sunset Boulevarde (1950), Ace In The Hole (1951), The Seven Year Itch (1955), Witness For The Prosecution (1957), Some Like It Hot (1959), The Apartment (1960) and One Two Three (1961). His comedies show a skilful examination and understanding of the sensitive interplay involved in human relationships. Bearing this in mind it doesn’t seem so unusual that he should turn his attention to the intriguing aspects of the relationship between the world’s greatest detective Sherlock Holmes and his biographer and good friend Doctor John Watson. The intention of The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes was to fill in what Arthur Conan Doyle had supposedly left out. Wilder loved the Holmes tales since he was a boy and could have filmed one of the existing stories but that wasn’t enough of a challenge – he wanted to explore the characters further and fill in certain gaps:

“We’re approaching the characters and the Baker Street atmosphere in a straightforward manner, with warm-heartedness and good humour. I love the stories and the last thing I would want to do is ‘guy’ them in any way. We hope to treat Holmes and Watson with respect but not reverence. There is a certain amount of natural humour, but the stories in our picture essentially show the relationships and friendships between the two men.” Wilder cast stage actor Robert Stephens in the lead, who was the original choice to play Holmes in A Study In Terror (1965) but was unavailable at that time. Colin Blakely, another actor seen more often on stage than screen, was chosen to play Watson. Christopher Lee was given the role of Holmes’ smarter brother Mycroft, thus making him the first actor ever to play both characters.

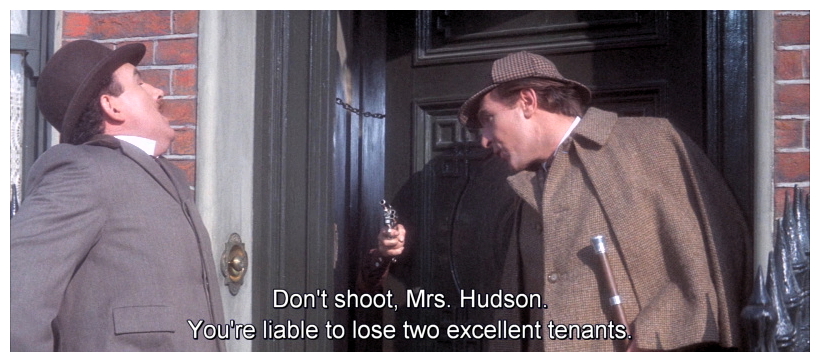

The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes was an extravagant production involving a nineteen-week schedule at Pinewood Studios with six weeks location shooting at Inverness. While filming on the banks of Loch Ness, the Scottish Tourist Board trade index increased by 200% and many happy visitors left with photographs of the Loch Ness monster, little realising it was a full-size film prop. One of the most impressive sets ever built at Pinewood was 150 metres of Baker Street with fully built-up fronts and smaller buildings receding in perspective, shops dressed with authentic Victorian bric-a-brac, real cobblestones and beery pubs. Taking four months to build, the set utilised more than a hundred extras in full costume and nineteen horse-drawn carriages. The Baker Street living-room is incredibly detailed and authentic, thanks not only to the expertise of production designer Alexander Trauner, but also Wilder’s meticulous attention to detail. In the hands of such talented filmmakers the movie was all set to be a winner but, unfortunately, something happened to it on its way to the cinema screen.

The original idea was to make a three-hour film presenting four separate stories, but the released result was just a single story only two hours long. A prologue reveals that in the vaults of a London bank lies a deposit box belonging to Doctor Watson with instructions that it not be opened until fifty years after the author’s death. Miklós Rózsa‘s superb theme music rises to a climax and the elegant credits begin. From this opening it seems apparent that we are in for some frank revelations concerning Holmes and his ‘censored’ cases. The opening scene is beautifully conceived, the most effective of Holmes parodies. Its success lies in the lightness of touch in the playing and writing, and is presented in such a way that one can sense a love and reverence for the character shining through. Holmes and Watson have just returned to Baker Street after another successful case solved. Watson examines his mail:

“Here’s an advance copy of the Strand magazine. They’ve printed The Red-Headed League. Would you like to see how I’ve treated it?”

“I can hardly wait. I am sure I shall find out all sorts of fascinating things about the case that I never knew before.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Oh come now, Watson, you must admit you have a tendency to over-romanticise. You have taken my simple exercises in logic and embellished them, embroidered them, exaggerated them.”

“I deny the accusation.”

“You have described me as six foot four whereas I am barely six foot one.”

“A bit of poetic licence.”

“You have saddled me with this improbable costume which the public now expects me to wear.”

“It was not me doing. Blame it on the illustrator.”

“You have made me out to be a violin virtuoso. Here’s an invitation from the Liverpool Symphony to appear as soloist in the Mendelssohn violin concerto. The fact is I could barely hold my own in the pit orchestra of a second-rate music hall.”

“You’re much too modest.”

“You’ve given the reader the distinct impression that I’m a misogynist. Actually I don’t dislike women, I merely distrust them – the twinkle in the eye and the arsenic in the soup.”

“It’s these little touches that make you colourful.”

“Lurid is more like it. You’ve painted me as a hopeless dope addict, just because occasionally I take a five per cent solution of cocaine.”

“A seven per cent solution.”

“Five per cent. Do you think I’m not aware you’ve been diluting it behind my back?”

“As a doctor as well as your friend, I strongly disapprove of this insidious habit of yours.”

“My dear friend as well as my dear doctor, I only resort to narcotics when I am suffering from acute boredom, when there are no interesting cases to engage my mind. Look at this – an urgent appeal to find some missing midgets.”

“Did you say midgets?”

“Six of them. The Tumbling Piccolos, an acrobatic act with a circus, disappeared between London and Bristol.”

“Don’t you find that intriguing?”

“Extremely so. You see, they’re not only midgets but also anarchists. By now they will have been smuggled to Vienna as little girls in organdie pinafores. They are to greet the Czar of all the Russias when he arrives at the railway station. They will be carrying bouquets of flowers and concealed in each bouquet will be a bomb with a lit fuse.”

“Do you really think so?”

“Not at all. The circus owner offers me five pounds for my services. That’s not even a pound a midget. So obviously he is a stingy blighter and the little chaps simply ran off to join another circus.”

“Sounded so promising.”

“There are no more great crimes anymore Watson, the criminal class have lost all enterprise and originality. At best they commit some bungling villainy with a motive so transparent that even a Scotland Yard official can see through it.”

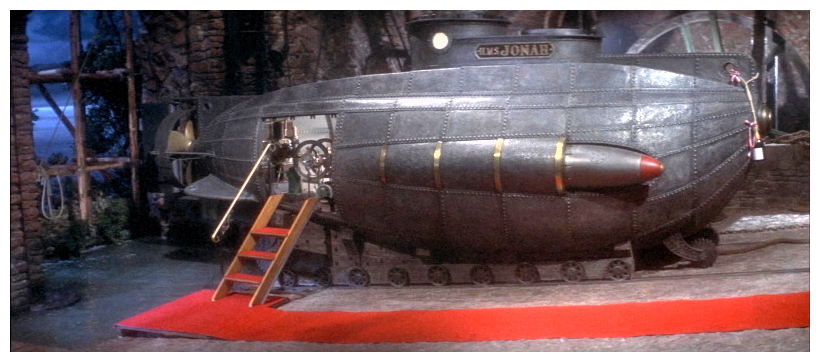

The entire scene is a joy to watch and is so successful because it only just crosses the borderline between homage and satire, so one can easily imagine Arthur Conan Doyle writing it while in a whimsical mood. It would hardly offend the most rigorous of Holmes purists but, alas, the same cannot be said of the rest of the film. Its gradual decline can be plotted from the end of this opening scene. The story moves onto the main mystery, described by Watson as the most outrageous in all their years together, in which Holmes becomes romantically attached to a member of the opposite sex. A Belgian woman by the name of Gabrielle Valladon (Genevieve Page) is fished out of the River Thames and brought to Baker Street. She begs Holmes to find her missing engineer husband, and the resulting investigation leads to a castle in Scotland. Along the way, they encounter a group of monks, some midgets and the Loch Ness monster. It turns out that Sherlock’s ‘smarter’ brother Mycroft (Christopher Lee) is involved in building a prototype submersible for the British Navy, with the assistance of the engineer Valladon.

When taken out for testing it was disguised as a sea monster, and the midgets were recruited as crewmen because they took up less space and needed less air. When they meet, Mycroft informs Sherlock that his client is actually a top German spy named Ilse Von Hoffmanstal, sent to steal the submarine, and the ‘monks’ were German sailors. Queen Victoria (Mollie Maureen) arrives for an inspection of the new weapon, but objects to its unsportsmanlike nature. She orders the exasperated Mycroft to destroy it, so he conveniently leaves it unguarded for the monks to steal (rigging it to flood and sink). Fräulein Hoffmanstal is arrested, to be exchanged for her British counterpart. In the final scene some months later, Sherlock receives a message from his brother telling him that Hoffmanstal had been arrested as a spy in Japan, and subsequently executed by firing squad. As Holmes reads the message an expression of deep sadness fills his face. He stares blankly for a few moments and then, leaving the breakfast table, he heads in the direction of his cocaine supply.

The suggestion of romance between the great detective and Madam Valladon is so subtle as to be downright vague. Actors Stephens and Page fail to convey the growing intensity of the relationship silently developing between them. As a result, some of their actions appear rather obscure and downright unnecessary. The film is far too leisurely to excite and Wilder’s usually racy wit is not only diluted by the Victorian era, but also by the pacing – it takes way too long to get to the point in what is, by Holmes standards, a simple mystery – which was another reason why it considered impossible to include the entire original shooting script. Where are the promised scenes of young Holmes at Oxford University? What happened to the sequence with Inspector Lestrade (George Benson) and the affair of the upside-down room?

The shooting schedule ran for six months and resulted in a rough-cut that came in at 200 minutes. The film was originally structured as a series of specifically linked episodes, each with a particular title and theme. The opening sequence was to feature Watson’s grandson in London claiming his inherited dispatch box and a flashback to Holmes’ Oxford days to explain his distrust of women. They were all filmed but deleted from the final print, because United Artists had suffered a number of major film flops in 1969 and were forced to cancel the intended format for Wilder’s massive project. Executives ordered the film to be cut to fill a regular theatrical running time, whittling it down to a mere 125 minutes. The episodic format made the pruning process relatively simple, losing the opening sequence, the Oxford flashback and two full episodes entitled The Dreadful Business Of The Naked Honeymooners (15 minutes) and The Curious Case Of The Upside-Down Room (30 minutes). Although most of the footage has been recovered, much of it is without sound.

The basic premise is interesting but the film fails to live up to it. Wilder seems vague about which way the film should go and inevitably it misses all his targets: too limp to be a satire; too laid-back to be a comedy; too frivolous to be a thriller. There are a few good scenes, particularly the opening, and some exchanges are amusing: “What’s that noise?” – “Mrs Hudson is entertaining.” – “I have not found her so.” Wilder and his writers also came up with a couple of authentic-sounding Holmesisms – “The art of concealment is being in the right place at the right time.” – but they do not seem part of a unified whole. Christopher Lee plays it straight as bald Mycroft in an effort to shrug off his famous Dracula persona, and Colin Blakely is a damn fine Watson who, in different circumstances, could portray a very authentic version of the doctor. Robert Stephens as Holmes is disappointing to say the least, presenting a far too romantic picture of Holmes with his easy movements, nasal drawl and wavy hair. His performance would have suited a portrayal of Oscar Wilde rather than Sherlock Holmes.

Like Heaven’s Gate (1980), Waterworld (1995) and dozens of other infamous Hollywood movies, The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes quickly developed a reputation as a budget blow-out. Wilder’s most expensive film ever at more than US$10 million, many viewers were left wondering where all that lovely money went. The scenes featuring the Loch Ness monster were intended to be filmed in the actual Loch. A life-size prop was built which had several Nessie-like humps used to disguise flotation devices. The humps were removed at Wilder’s demand. Unfortunately, during a test run in Loch Ness, the monster-prop sank and was never recovered. A second prop was built, a miniature with just the head and neck, and was filmed in a studio tank. Actress Genevieve Page: “When we lost our Loch Ness monster, he wasn’t too concerned, even though he was also the producer. He was more concerned about how the man who made it felt when all his work sank to the bottom of the Loch Ness. He went over and comforted him.”

Wilder is most successful in the scenes featuring actual detective work and the way he captures the essence of the period (however fleeting), which only makes one regret that he did not try to present a more straightforward Holmes story. Despite some encouraging reviews the film was poorly distributed and received virtually no response from filmgoers, eventually becoming a staple for film societies and encore cinemas. Not only did the failure of The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes deny fans further new adventures of the world’s greatest detective, but it also revealed how risky Holmes had become as a film subject, which is why there have been so few straightforward Holmes movies since. Four decades later writers Steven Moffatt and Mark Gatiss, directly inspired by The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes, created the updated television series Sherlock. A very good show with excellent performances from Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman, it nevertheless failed to capture the essence of what made the original stories so exciting. The Victorian setting is as important to a Holmes story as any character and, without its period setting, becomes little more than just another gimmicky detective we’ve seen a hundred times before, from Monk to Dirk Gently. Leaving you with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the underbelly of the dark side of cinema for…Horror News! Toodles!

The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes (1970)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews