SYNOPSIS:

When Senator Charlie Roan decides to run for President in order to finally end the annual bloodbath known as The Purge, she becomes the prey in a deadly hunt that could not only end her campaign, but her life as well; if she wants to survive this election year and turn back the clock for America, she’ll have to accept the help of Leo Barnes – and a small group of rebels who may have their own kind purge in mind.

REVIEW:

He had made sure everyone except his ten year old son, Akia, was out of the house that evening; his wife he sent away with a lie about her mother wanting to see her in the village; little Dembe and her older sister, nine year old Kijai, were handed off to friends who would entertain them at the nearby children’s club, playing Kakopi or Stockings. Everything was ready for the ceremony, except Polino himself; despite his belief in the absolute authority of his mentors, what they demanded of him was still too much, he felt. How could a man be expected to do this to his own flesh and blood, his own son, regardless of the reward?

In the back of the house, away from prying eyes and ears, in an area lit only by a circle of ceremonial candles, Akia was lying face-down on a bed of leaves which had been blessed with holy water and spirit smoke from smoldering corn stalks; the mango tree from which the leaves had come (the initiators had assured Polino) housed incredibly powerful mayembe, the ones that had chosen him, the ones that would guide and protect him and give him great power, but only if he performed the ceremony as instructed. Waving the kindled stalks just above the prostrate boy, Polino began to chant rhythmically, reciting prayers to the mayembe of the east, the west, the north, and the south, the Holy Guardian Demons which would grant him power over others and give him great wealth beyond his wildest dreams.

Now, setting the corn stalks aside, he lifted a large machete from the nearby table and gently touched the blunt backside of the blade to the back of Akia’s neck, just below the skull, while reciting more prayers beneath his breath. He raised the blade a quarter of an inch and then gently brought it down, delicately tapping Akia’s neck. After a few moments and more prayers, he raised the blade and gently tapped the nape of Akia’s neck for a second time. Sweat poured from Polino’s face. The boy squirmed slightly and almost looked up at him, almost looked into his father’s eyes, but Polino suddenly barked for him to hold his place; as he tapped for a third time, anguish contorted Polino’s face. Hesitantly, he took the dead chicken near his feet, swiftly removed its head with the machete, and waved the carcass over Akia, spraying the boys back with blood. Akia twitched slightly, but remembered his father’s earlier command to be still.

Polino tossed the chicken aside and tightly closed his eyes, then he began to rock back and forth, chanting in a low baritone that sounded more like a soft growl rather than a human voice petitioning the spirit world. He tapped the boy’s neck again, then gathered his nerve, faltered slightly, then suddenly flipped the machete around, raising it high, and brought it down viciously, severing Akia’s head. Blood flowed like a waterfall, covering the floor and Polino’s feet. Jumping back, he faltered for mere seconds before he lifted the boy’s body, flipping it onto its back, and swiftly slitting it open from neck to groin; to finish the ritual that would make him a fully blessed witch-doctor, Polino would take his son’s ruptured body, slide his arms around the ribcage beneath the slit skin, wearing him like an apron while dancing in the moonlight.

Most people, when they hear the phrase “Human Sacrifice”, tend to picture a far off time in the distant past, a time far from themselves and their civilized modern lives. The practice does go back to at least the Neolithic period and occurs frequently throughout time, and shockingly, right up to our own. As for Akia and his sacrifice detailed above, it’s a true story, with only minor embellishments, and it took place only a few years ago in Uganda, where child sacrifice is so prevalent, a special police task force has been set up to fight it.

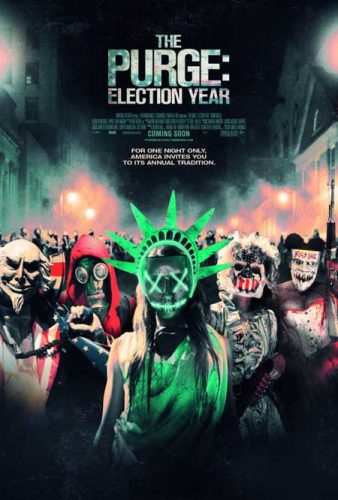

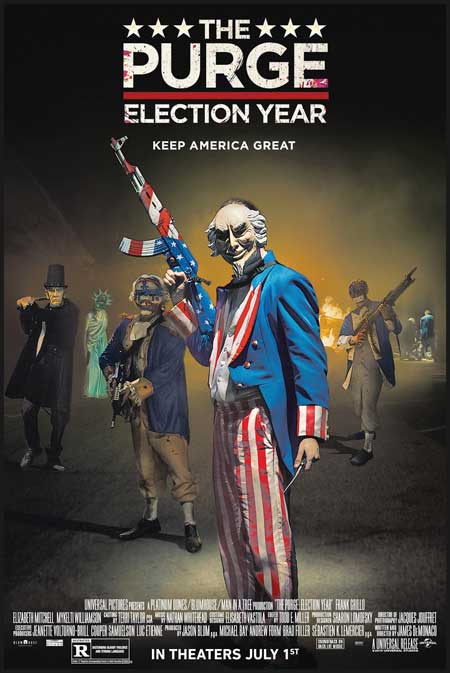

With The Purge: Election Year (as with the previous two films), Writer/Director, James DeMonaco has drastically narrowed the distance between the nebulous, fictionalized (and sanitized) idea of human sacrifice and brought it much closer to home; by setting the story in America and in our current time, he’s taken the debauched brutality of something like the ancient Aztec sacrifices and made it quite tangible and extraordinarily disturbing. In this film, he’s deftly put all of humanities viciousness on display, sharpening it up even more by not only mocking humanity’s unquenchable avidity, but by accentuating the very fragile, and very illusory, structure of the electoral process. His writing is solid, and his ability to keep the story acute yet sinuous, with striking visuals at virtually every turn, seems to have only gotten better since the first film: disturbingly childlike masks abound, hulking giants covered in blood appear then disappear as if in a dream, bodies engulfed by flames pass by without comment, guillotining in alleyways lit only by trashcan fires slowly drift into view then out again as the main characters traverse this nightmare landscape. It’s as if Wes Craven, instead of Fellini, had directed La Dolce Vita.

The cast is superb, with Frank Grillo reprising his role of Leo Barnes from The Purge: Anarchy, but now he’s taken on the position of Senator Charlie Roan’s (Elizabeth Mitchell) Chief of Security. He’s just as gritty, gravelly and tough as ever, but with a slightly more altruistic bent this time around. Elizabeth Mitchell is wonderful as the determined, but definitely naive, Senator. Mykelti Williamson and Joseph Julian Soria as Joe Dixon and Marcos, respectively, do a fine job of providing a touch of levity and warmth to the otherwise barbarous goings on. And Terry Serpico as the neo-Nazi skinhead mercenary, Earl Danzinger, hunting down Senator Roan is the epitome of callous, knuckle-dragging brutality.

Jacques Jouffret’s dense, yet ethereal, cinematography embroiders the phantasmal Gehenna the country becomes during The Purge; his lights and darks, though rich, have been reduced in such a way as to blur the two together, creating a creamy stream of color that augments the nausea of the visuals. Not only is the film beautiful to look at, the acting accomplished, the writing and directing skillful and polished, the theme and its execution (pun intended) are also smart and extremely thought provocative. A savvy film with a lot to say and definitely worth multiple viewings, if your conscience and stomach are tough enough to take it.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews