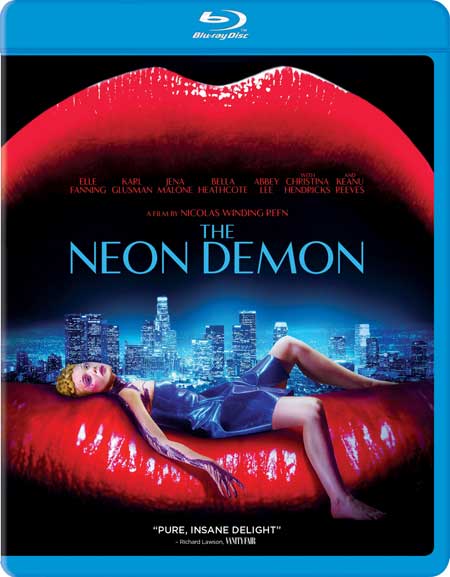

SYNOPSIS:

After Jesse, a callow and unsophisticated teenage girl, finds herself in Los Angeles at the behest of an amateur fashion photographer she met online, other people higher up the modeling world food chain begin to take a distressingly omnivorous notice of her unripe purity.

REVIEW:

Inspired by Roger Vadim’s Et Mourir de Plaisir (USA, Blood and Roses), Nicholas Winding Refn’s retelling of La Fanu’s classic vampire story, Carmilla, has taken a prismatic ride on the tails of cinematographer Claude Renoir’s Technicolor dream coat; but, in a stroke of originality building on Vadim’s beautiful, if flawed, original film (which would go on to influence Mario Bava’s Black Sabbath and Dario Argento’s Susperia), Refn has moved the setting away from dusky, gothic castles high up in the Austrian mountains, as tradition calls for, and transported the story to the cattie modern world of L.A.’s youth-obsessed modeling industry; also changed are the familiar hoop underskirts and elaborate lace fringe which are replaced with plastic mini-crop tops tight enough to break ribs that haven’t already been removed for cosmetic reasons and quantities of glitter make-up sufficient to blind the sun.

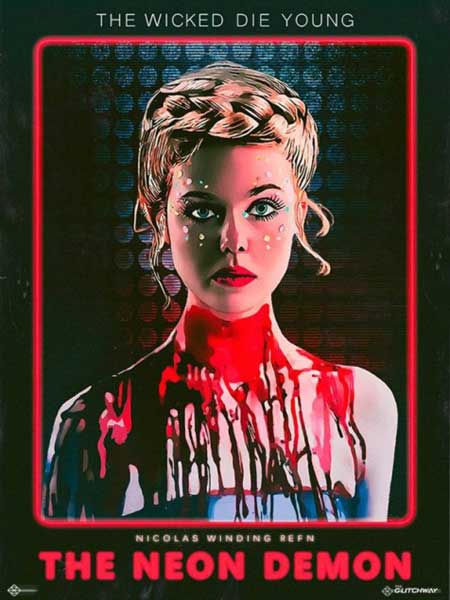

Elle Fanning stars as Jesse, the new kid in town whose downy pubescence everyone seems to crave; she has that velvety, morning-dew freshness that they’ve all lost but either desperately want to regain or corrupt, depending on the leering character’s particular state of degradation. The lusty hunger begins instantaneously with the opening scene when Dean (Karl Glusman), a want to be fashion photographer who found Jesse online, has her pose for him in a shiny neo-Victorian diorama, fake blood running from a fake cut throat, one arm hanging, everything still, and her eyes unblinkingly vacant, like those of a porcelain doll; in between shutter clicks, he moves the camera away and reveals he’s giving her the old raincoat pirate’s unnerving eagle eye, precisely setting up the film’s underlying themes of mesmerized ravenousness, cupidity, and envy with a little emptiness thrown in as a binder.

Without saying a word, the scene shifts to the dressing room where Jesse is wiping the theatrical blood from her alabaster skin, while the next predator, Ruby (Jena Malone) – who appears to be everyone’s go-to make-up artist for L.A. fashion shoots – tries to hide the fact that she’s giving Jesse the silky once-over. She invites Jesse to a party later, which turns out to be a fairly subdued rave consisting of a blanket of purple-tinged blue lighting, blown out and distorted techno music, and Jesse’s next two predators, Gigi (Bella Heathcote) and Sarah (Abbey Lee), models who physically portray their identities perfectly by being young, slight, and sharply angular.

Characters of various base needs and longings follow: Hank (Keanu Reeves), the coarse and nearly bestial manager of the shabby motel where Jesse is staying and who has a skeezy eye for the tweens; Jack (Desmond Harrington), the overly-serious, self-important fashion photographer who’s looking for the new, fresh young thing to photograph, preferably in the nude; Robert Sarno (Alessandro Nivola), top-flight fashion designer who treats people like cattle and considers beauty to be the highest currency people have, and without it, they have nothing at all, he says.

The beginning of Jesse’s inevitable turn from innocence is done with subtlety, following the scene in modeling agent Roberta Hoffman’s (Christina Hendricks) office; she tells Jesse she’s seen other girls come into the office before who were good, but Jesse’s got that something special, that something that will make her great.

In the next scene, back at the motel, Jesse, at first nervous and unsure of herself, eventually seals her fate and takes the plunge, forging a signature on the parental consent form required for her to start modeling; afterward, in various scenes building upon one another, she begins to feed off of the compliments everyone is paying her, feeding off of the very hunger that they have for her; she begins to grow in confidence, siphoning off the electricity of those around her, becoming just as cynical and self-absorbed as they are; Dean, who seemed on the verge of consuming her with his eyes in the opening scenes, but having finally become a nearly forlorn protector of her, is cruelly brushed aside by Jesse when he asks her if she wants to be like them, and she replies haughtily: “I don’t want to be them. They want to be me”, summing up the whole Ouroboros essence of the modeling industry, celebrity, and vampirism, which, in the film, is a metaphor for both.

While Director Nicholas Refn’s debt to both Vadim and La Fanu is obvious, he shows an artist’s ability to originate and modify sufficiently enough to make a work his own rather than just an adaptation; and although using the Transcendentalist’s approach of slow filmmaking at times, he does keep the story appropriately coherent, quite a bit of blood flowing in the third half, and the gruesomeness surprisingly elevated, so much so that a less tolerant audience can follow without much yawning. Natasha Braier’s cinematography is, without a doubt, stunning; Claude Renoir’s rich colors are evident throughout, but Natasha has been able to add a kind of brittle sharpness to them which has accentuated Refn’s unconventional form of vampirism. The tinkling score by Cliff Martinez adds an exquisitely eerie lightness to an otherwise heavy subject, fleshing out the premise and complementing Braier’s cinematography.

The acting on all counts is unequivocal, consummate, and at times brilliant; Jena Malone is delicately corrosive; Bella Heathcote and Abby Lee are, at turns, covetous, jaundiced, and simpering; Elle Fanning floats on her innocence to begin with, then turns convincingly glassy as things progress; Desmond Harrington plays the one note he’s given to perfection; Keanu Reeves slithers with confidence; Karl Glusman’s Dean takes the exact opposite tour of Elle Fanning’s Jesse, leaving the viewer feeling sorry for him, remarkably enough; but Alessandro Nivola’s performance as Robert Sarno may be the standout, his understated moments exposing every attenuating moral, every faint bit of unrecognized pollution, every smug conceit that his character has; a truly great interpretation well worth seeing in an already significant work of film making.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews